Can we detect polygenic selection within Europe without being fooled by population structure?

Why would northern Europeans be genetically predisposed to a darker retina? And can we detect that kind of within-Europe divergence without the usual stratification traps?

Detecting polygenic adaptation in humans has proven to be harder than many expected. Over the past decade, several studies reported geographic patterns in polygenic scores for traits such as height or educational attainment, often interpreted as evidence of recent selection. More recent work has raised methodological concerns, particularly about the role of subtle population stratification in genome wide association studies. These concerns do not show that polygenic adaptation does not exist, but they do make clear that distinguishing selection from shared ancestry is statistically difficult. This is also the motivation for my own analyses of ancient DNA time series, where the same question keeps coming up: when a polygenic score changes across populations or time, is it selection, drift, or mixture?

A recent study by Yuan et al. (2026) on retinal pigmentation is a useful case study. It combines a novel AI-based phenotyping approach with a selection framework that explicitly models population structure. And it has teeth: within Europe the genetic score shows an unusually strong geographic gradient, the direction runs counter to the familiar iris-color story, and the same genetics also stratifies modern risks like myopia and skin cancer.

From images to a genetic phenotype: DeepGRP

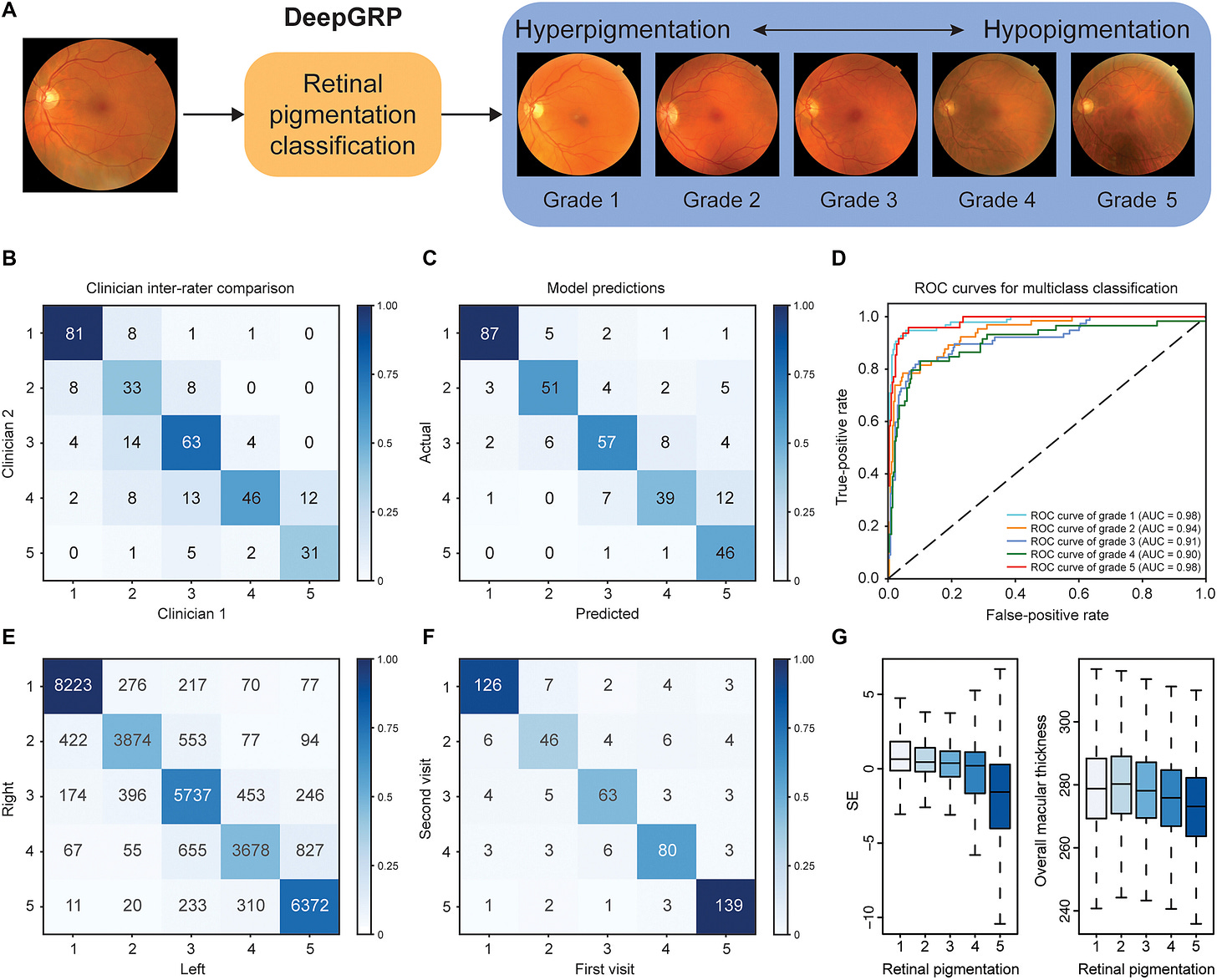

A central novelty of the study is how the phenotype is constructed. Retinal pigmentation has traditionally been assessed qualitatively by clinicians, making it unsuitable for large scale genetic analysis. The authors address this by developing DeepGRP, a deep learning model trained on high quality retinal fundus photographs that have been graded by expert ophthalmologists.

The model learns to assign each image to one of several ordered pigmentation categories, ranging from more heavily pigmented fundi to more hypopigmented ones. After extensive quality control, this approach produces a standardized quantitative trait for tens of thousands of individuals. In other words, artificial intelligence is not used to infer genetics, but to solve the phenotyping bottleneck that usually limits genome wide association studies of complex traits.

Figure 1. Overview of the DeepGRP approach. Retinal fundus images are processed by a deep learning model trained on expert graded images to produce a standardized retinal pigmentation phenotype. This AI derived trait is then used in a genome wide association study to construct a polygenic score for retinal pigmentation (Yuan et al., 2026).

Using this AI derived phenotype, the authors perform a GWAS and construct a genetic score for retinal pigmentation. Importantly for interpretation, higher genetic scores correspond to lower retinal pigmentation, meaning a lighter fundus.

How the authors address population stratification

Any geographic pattern in polygenic scores raises the question of confounding by population structure. This issue has been discussed extensively in the context of height and educational attainment. The concern is not that selection is impossible, but that residual ancestry effects in GWAS summary statistics can generate spurious correlations with geography.

What distinguishes this study is the method used to test for selection. Rather than relying only on correlations between polygenic scores and latitude, the authors also use the Qx statistic, a test introduced by Berg and Coop (2014) for detecting polygenic adaptation using allele-frequency data. Qx asks whether the set of trait-associated alleles is more differentiated across populations than expected under genetic drift, once you account for their shared demographic history. The key ingredient is a population covariance matrix estimated from genome-wide neutral variation, which defines the null expectation for how allele frequencies should co-vary under structure and drift. Trait SNPs are then evaluated against that baseline.

Consistency of the genetic signal across traits and ancestries

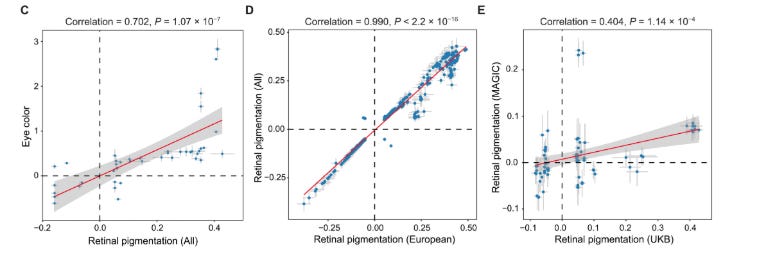

Before turning to geographic patterns, the authors first ask a simpler question: is the genetic signal they identify internally consistent, biologically plausible, and stable across analyses? Figure 2, panels C–E, address exactly this point.

Figure 2C–E provides quick sanity checks on the GWAS signal. In panel C, the lead SNP effects correlate with published eye-color GWAS effects (r = 0.702), suggesting overlap with known pigmentation biology, even if retina and iris pigmentation are not the same trait. In panel D, European-only and cross-ancestry effect sizes are almost identical (r = 0.990), arguing against a cohort- or ancestry-composition artifact. In panel E, effect sizes are still positively correlated in an East Asian dataset, though less strongly, consistent with shared architecture plus expected differences in LD, allele frequencies, and phenotype definitions across ancestries. This replicates mine and others findings of a shared genetic architecture between EAS and EUR for educational attainment and height.

A possible confusion is that panel C shows SNP-level alignment with eye color, while later the population-level score trends toward darker retinal pigmentation at higher European latitudes. These are not contradictory. Panel C is about effect directions across traits, whereas the latitude analysis is about allele frequencies across populations. Shared effects do not imply the same geographic cline.

From a GWAS signal to an evolutionary pattern

The next step is the one people actually care about: once you aggregate those SNP effects into a genetic score, what does the score look like across populations, and does it line up with geography or plausible environmental pressures?

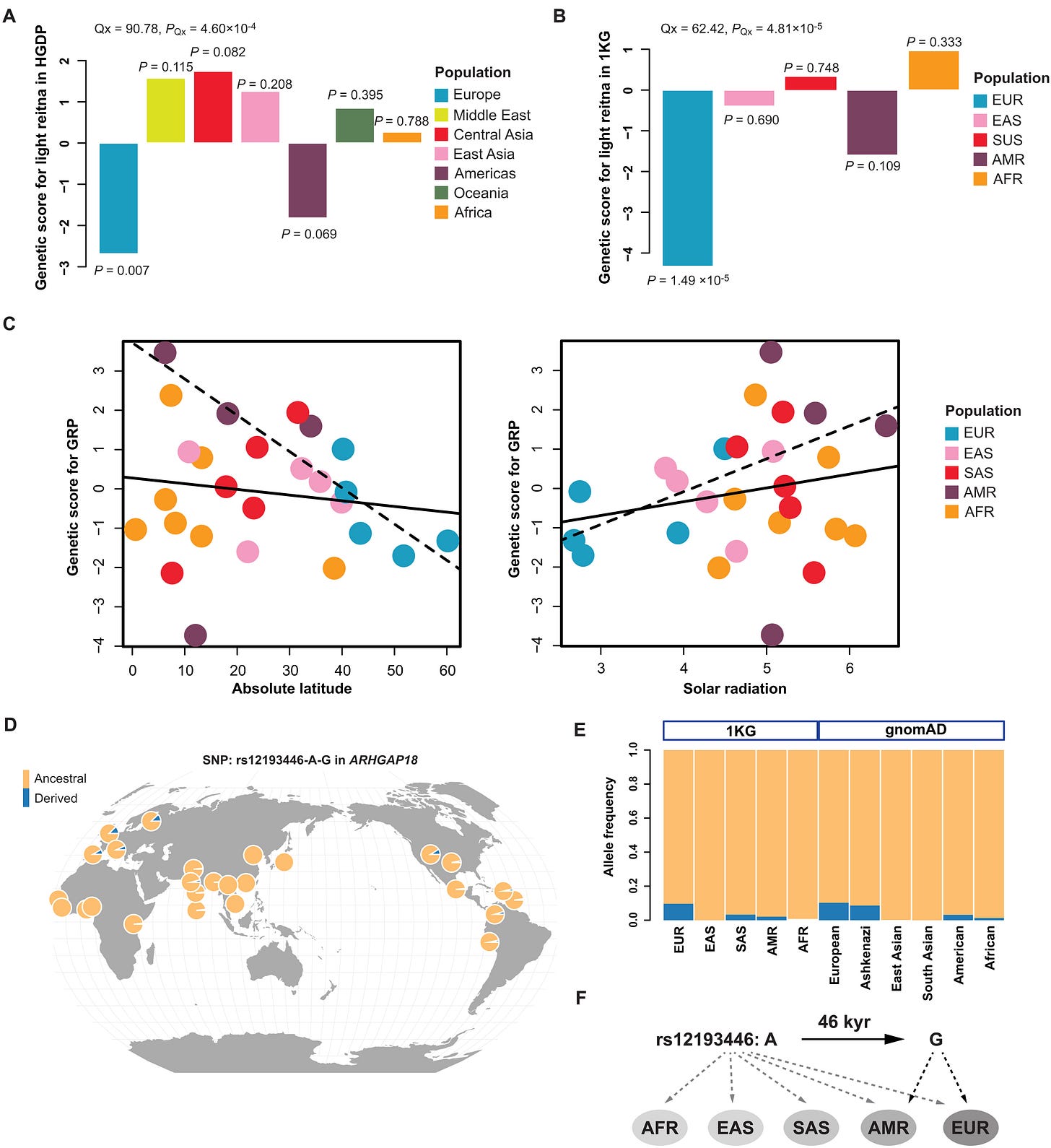

That is what Figure 5 addresses. It is the paper’s main “bridge” figure, moving from associations in individuals to structured patterns across populations.

Genetic scores across super-populations

The first panel (A) summarizes the genetic score by broad super-populations. Differences at this scale are not surprising for a pigmentation-related trait. Europeans have the lowest scores, whereas Middle Easterners and South Asian populations have the highest. Africa’s scores are in the middle. This is a bit surprising, but it’s possibly due to LD decay reducing the predictive accuracy.

Latitude and solar radiation

The next panels relate population-level genetic scores to geographic and environmental variables. Across all populations, the association with absolute latitude is modest, and the correlation with annual solar radiation is weaker and not statistically robust. The striking result emerges when the analysis is restricted to Europe. Within Europe, the genetic score shows a very strong negative correlation with latitude (r ≈ −0.9), and a correspondingly stronger relationship with solar radiation, while the association largely disappears outside Europe.

Interpreting the sign is important. Higher genetic scores correspond to reduced retinal pigmentation, meaning a lighter fundus. The negative correlation therefore implies that populations at higher European latitudes are genetically predisposed to darker retinal pigmentation.

This is counterintuitive if one has iris color in mind, since lighter irises are more common at higher latitudes. However, retinal pigmentation and iris pigmentation are distinct traits with different functional roles. Iris pigmentation affects how much light enters the eye, whereas retinal and choroidal pigmentation influence internal scatter and glare. In high-latitude environments, especially those with snow or ice, reflected light and glare can be intense despite lower average illumination. Darker retinal pigmentation can plausibly reduce stray light and improve visual contrast under such conditions, so there is no requirement that the two traits follow the same geographic gradient.

A candidate allele with an informative history

Figure 5 also highlights one intronic variant, rs12193446 in LAMA2, described as regulating ARHGAP18. The allele-frequency pattern is highly asymmetric across regions. The ancestral allele is nearly fixed in African populations, whereas the derived allele is notably more common in Europeans and rare or absent in East Asians and uncommon in Americans.

To place this in time, the authors use allele ages from a genealogical inference dataset. The derived allele is estimated to be on the order of roughly 1850 generations old (~46,328 years). This timing overlaps with the period of modern human dispersal into Europe. That does not prove selection, but it establishes that at least one allele contributing to the score is old enough to have participated in Eurasian differentiation rather than being a very recent, local mutation.

The dark side of a dark retina

The same genetic score that tracks retinal pigmentation also slices the cohort into very different risk profiles for myopia. The gradient is not subtle. People in the highest PRS decile have roughly a 4.6× higher risk than those in the lowest decile, with a clean dose–response across deciles, and it survives adjustment for the obvious confounders like age, sex, refractive measures, self-reported skin color, and sunlight variables.

And it does not stop at the eye. The GRP-derived PRS is also associated with skin cancer, with the top versus bottom decile around 1.7× higher risk, still detectable after covariate adjustment. Risk rises with age as expected, but genetics shifts the baseline.

The authors also report genetic correlations with retinal detachment and cataract, but when they try to push toward causality using one-sample Mendelian randomization (accounting for refractive error), the evidence does not support a direct causal role for retinal pigmentation itself. Unfortunately, it looks like the genetic architecture around ocular pigmentation sits in the same neighborhood as traits with medical consequences.

What comes next

So far, this discussion has focused on present day populations. A natural next question is whether the same pattern can be observed through time. Did this north–south divergence in retinal pigmentation emerge recently, or does it have deeper roots in European prehistory?

Part II (for paid subscribers) will look at the same genetic score in ancient genomes to track how this cline changed over time, and how it relates to major demographic and environmental transitions in prehistoric Europe. Stay tuned.

References

Berg, J. J., & Coop, G. (2014). A population genetic signal of polygenic adaptation. PLoS Genetics, 10(8), e1004412.

Jian Yuan et al. (2026). Genome-wide association study reveals genetic architecture and evolution of human retinal pigmentation.Sci. Adv.12, eadw7768.DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adw7768