"Colourism" in the Sperm Bank: Who Gets Picked

Israel’s survey results and the global Danish donor effect

Ari Nagel—6′2″, blue-eyed, with curly brown hair—has reportedly fathered about 176 children worldwide. He became Israel’s most controversial donor when the High Court blocked the use of his non-anonymous samples and ordered stored vials destroyed, underscoring how charged “donor choice” is in a system built on anonymity. Beyond courtroom drama, markets elsewhere show that looks do matter: in an Australian clinic dataset (1,546 reservations), donors’ eye and hair colour influenced how quickly profiles were picked—though the study doesn’t reveal which specific colours led (Whyte et al., 2016).

Sperm donation in Israel dates back to the late 1970s and was formalized in the early 1990s under a strongly medicalized model. Historically, physicians matched anonymous donors for married heterosexual couples. Over time, though, use shifted away from male infertility and toward single and lesbian women, who now make up a large share of recipients.

Against that backdrop, a little-known 2002 study asked 285 Jewish-Israeli patients across four hospital sperm banks: if you could choose, what would your ideal donor look like? (Birenbaum-Carmeli & Carmeli, 2002). Their answers revealed a tug-of-war between wanting a child to resemble oneself or one’s partner and reaching for a narrow, high-status look.

Who was surveyed & how

Participants: 128 married/cohabiting women, 85 single women, 72 men. They compared a hypothetical donor’s height, eye colour, and skin tone with either their partner’s features (for couples) or their own preferences (for singles/men). These were hypothetical picks—useful for spotting cultural desires rather than actual purchases.

The headline: a “Prince Charming” template

Across traits, preferences converged on an ideal: ~1.80 m tall, light-eyed (green/blue), white/white-swarthy skin—what the authors dub Israel’s “Prince Charming.” Deviations from the partner’s look were usually modest, keeping resemblance plausible.

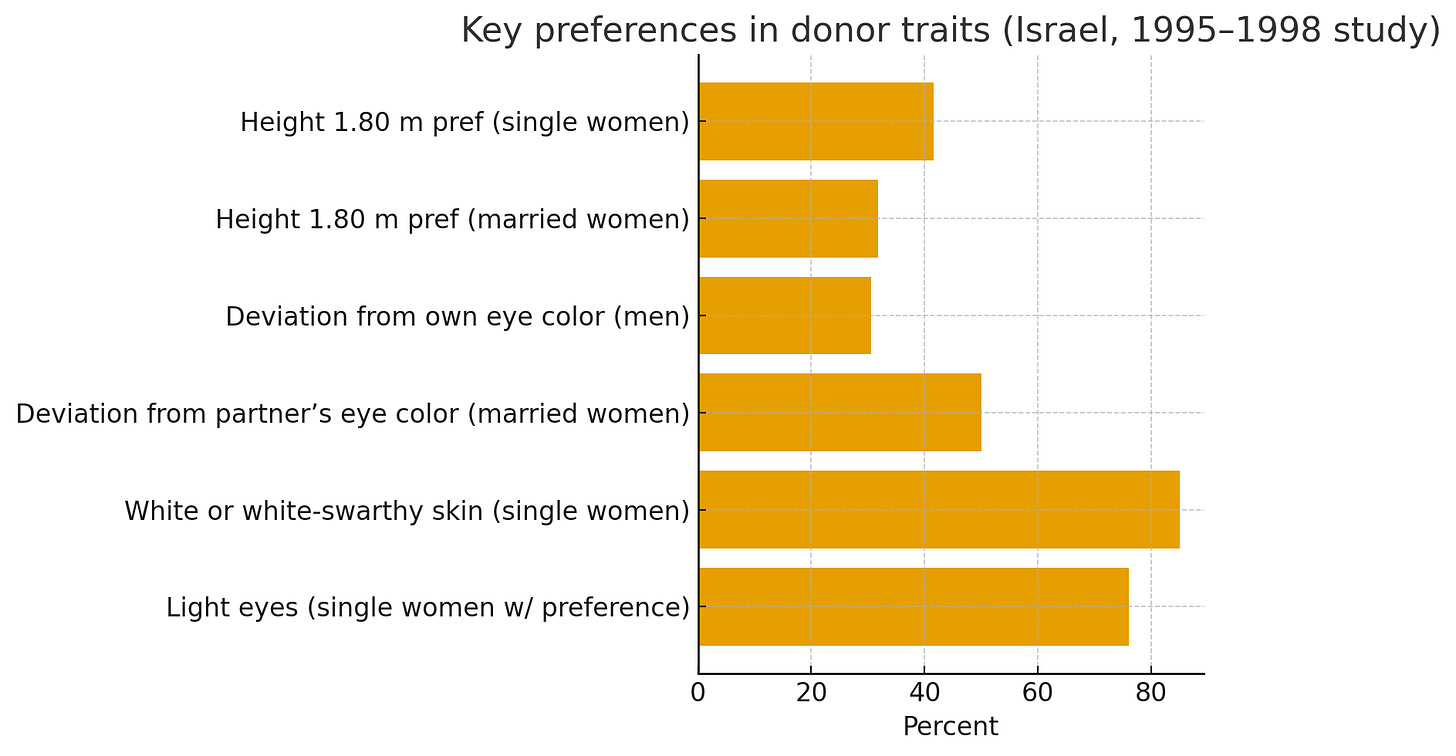

Key stats at a glance

Height: 1.80 m became the sweet spot

Among married women, 1.80 m was the modal choice (31.8%); among single women, preference clustered even more on 1.80 m. Men ≤1.78 m were most likely to want a taller donor (56.5%). This height is higher than the Israeli men average height, but not very much.

Eye colour: women drifted lighter

50% of married women were willing to deviate from their partner’s eye colour (vs 30.6% of men), and women’s deviations skewed lightward (McNemar p = 0.029; men n.s.). Single women who expressed a preference chose 76% light eyes.

Skin tone: the least flexible trait

Only four married women reported no preference on skin tone. Women’s deviations from partner were again asymmetrical toward lighter (McNemar p = 0.001). Among single women, 85% preferred white or white-swarthy donors.

Israeli context: when traits signal group boundaries and status

In Israel, the pull toward lighter eyes/skin and taller height can index internal boundaries. Lighter complexions/light eyes are more associated (in everyday reading) with Ashkenazi backgrounds; darker complexions/eyes are more common among Mizrahi Jews and among Arab/Palestinian citizens. The Birenbaum-Carmeli & Carmeli study connects lighter traits to Ashkenazi privilege, making “colourism” especially obvious in Israel. Women, more responsive to status cues, often reflect this in their choices of donor traits.

A note on the global “Danish donor” effect

Outside Israel, where recipient choice is common, market forces amplify a narrow ideal—nowhere more visibly than the international tilt toward Danish donors. Reporting indicates that roughly a fifth of donor sperm available in the UK is imported from Denmark; some Dutch clinics rely on Danish banks for >60% of treatments; in Belgium, an estimated 6 in 10 donor-conceived children have a biological Danish father. UK figures around 3,000 imported samples in a single year have been cited.

Markets also reflect demand in stark ways: in 2011, Cryos—then the world’s largest sperm bank—said it was turning away red-haired donors due to low demand relative to supply.

Do donor-trait picks mirror partner preferences?

Largely yes for height and colourism, and probably yes for “light-eyed/European looks”. Dating-market research shows a premium for taller men, persistent racial/skin-tone hierarchies, and algorithmic/product choices that can reinforce those patterns (e.g., filters, ranking). These directions match the study’s tilt toward light, tall, blue.

Eye colour is seldom isolated in dating studies, but the Danish-donor demand for light-eyed, fair phenotypes suggests nordic traits draw attention—consistent with the Israeli survey’s light-eye pattern.

Large-scale analyses of OkCupid messaging patterns show that white men receive more replies from women than men of other ethnicities. The same studies find a persistent racial hierarchy in women’s responses: Black and Asian men tend to get fewer replies, while white men are consistently at the top.

Conclusion: resemblance, ideals, and the politics of choice

From Ari Nagel’s blocked samples to the “Prince Charming” template in Israeli surveys, and the global tilt toward Danish donors, the lesson is clear: when choice enters the fertility market, looks matter. Sometimes it’s about resemblance to oneself or one’s partner, but often it’s a subtle drift toward height, light skin, and light eyes.

The Israeli data add a sharp wrinkle: women were more likely than men to nudge donor traits lighter, especially for skin colour. Men mostly stuck with their own look; women more often opted for a child who might appear a shade fairer, or with lighter eyes.

These findings open a broader question: are women everywhere more likely than men to lean toward lighter traits, or is this especially marked in countries where lightness signals ethnic or class advantage, like Israel? Future studies will need to tease apart whether the tilt toward a “whiter” look is mainly a status cue shaped by today’s social hierarchies or whether there are also biological preferences for certain appearances at play. Only then can we know if what looks like personal choice is actually cultural inheritance, human instinct or, most likely, some blend of both.

How to Support The Genetic Pilfer

If you enjoy this newsletter and want to help it grow, here are a few ways you can support my work:

💡 Subscribe or upgrade to paid

A paid subscription includes:

Full access to all posts and the archive

Exclusive content (apps such as the Population Genetic Distances Explorer or the Polygenic Scores Explorer)

The ability to comment and join the chat

👍 Like & Restack

Click the buttons at the top or bottom of the page to increase visibility on Substack.

📢 Share

Forward this post to friends or share it on social media.

🎁 Gift a Subscription

Know someone who’d enjoy The Genetic Pilfer? Consider giving them a gift subscription.

Your support means a lot — it’s what keeps this project alive and growing.

Thank you,

Davide

References

Birenbaum-Carmeli, D., & Carmeli, Y. S. (2002). Physiognomy, familism and consumerism: preferences among Jewish-Israeli recipients of donor insemination. Social science & medicine (1982), 54(3), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00035-1

Whyte, S., Torgler, B., & Harrison, K. L. (2016). What women want in their sperm donor: A study of more than 1000 women’s sperm donor selections. Economics and human biology, 23, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2016.06.001