From Dark Skin to Milk: How Evolution's "Accidents" Became Our Ideals

The Uncomfortable Mirror of Our Evolution

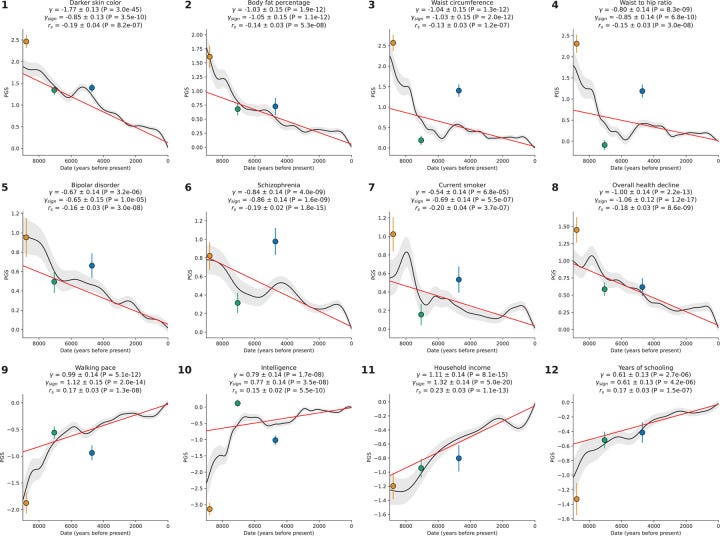

When we trace humanity's journey from scattered hunter-gatherers to our current global civilization, we encounter an unsettling pattern. Over the past 12,000 years, we've witnessed dramatic biological changes: enhanced disease resistance, lactose tolerance, altered stress responses, and cognitive adaptations that seem almost too perfectly suited to complex society. This evolutionary trajectory feels disturbingly deliberate—like a biological optimization program that improved our species. The question haunts us: Does this look like eugenics? The charts below show the trend in a dozen polygenic scores in the last 12K years. Arguably, they all show trends in the “right” direction:

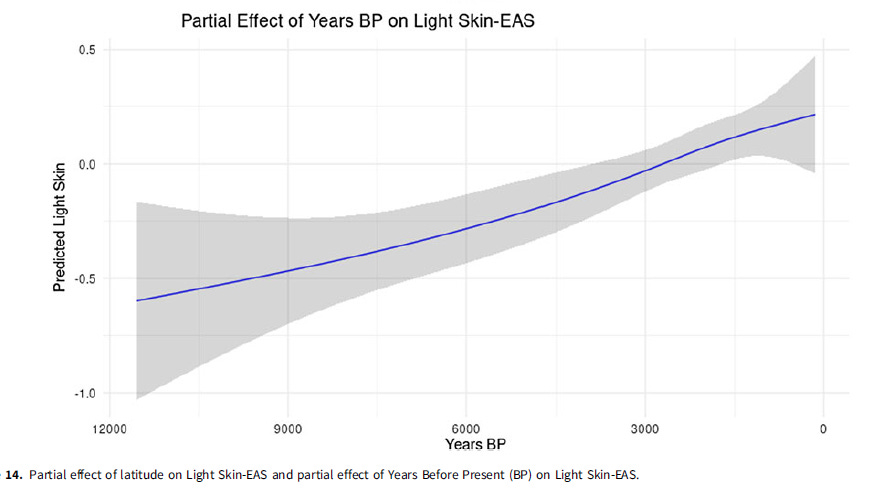

This study (Akbari et al., 2024) replicated the effects found by my previous study (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024) which additionally found positive selection for Autism Spectrum Disorder PGS and negative for Depression. Remarkably, the same selection pressures for IQ, EA, Autism Spectrum disorder and skin pigmentation also took place among East Asians (Piffer, 2025), along with selection against generalized anxiety disorder. For example, this show the increase in light skin pigmentation polygenic scores among East Asians (Piffer, 2025).

Two competing theories attempt to explain why our recent evolution feels so purposeful, yet they lead us to a remarkable convergence. Whether we view these changes as pragmatic survival adaptations or steps toward an abstract ideal of human "goodness," both perspectives ultimately compel us toward selecting for the same traits in our future.

Theory A: The Pragmatic Survival Lens

The first explanation frames our evolutionary changes as purely practical adaptations to the radically new environments we created. Dense settlements, agriculture, and social hierarchies demanded biological solutions, and natural selection provided them through brutal trial and error.

This perspective offers compelling evidence. Disease resistance genes spread because dense populations created pandemic conditions—those who survived plague, smallpox, and malaria passed on protective variants. Dietary adaptations like lactase persistence and enhanced amylase production emerged because agriculture introduced new foods that required new digestive capabilities. Cognitive and behavioral modifications helped humans navigate complex social hierarchies and delayed gratification systems that agricultural societies demanded.

Under this lens, these traits weren't inherently "good" in any moral sense—they were contextually advantageous. Disease resistance genes only mattered when diseases were present. Grain-processing abilities only helped when grains became dietary staples. These adaptations were reactive responses to environmental pressures we inadvertently created, not steps toward an idealized human form.

The adaptation theory treats our evolution like any other niche specialization. We don't consider polar bear fur "eugenic progress"—it's simply an adaptation to Arctic conditions. Similarly, humans adapted to the unique niche of agricultural civilization, developing the biological tools necessary to survive within the structures they built.

However, this mechanistic view faces significant challenges. It struggles to explain why we perceive certain evolutionary outcomes as "improvements" rather than mere changes. The theory also glosses over the trade-offs: genetic diversity lost, new diseases of civilization that emerged, and mental health challenges potentially linked to our biological mismatch with modern environments.

Theory B: The Abstract Good Lens

The second explanation suggests our evolution feels eugenic because it appears to align humanity with universal principles of "good"—increased complexity, intelligence, cooperation, and well-being. Under this view, evolution, whether blind or not, inadvertently progressed toward outcomes we intrinsically value.

This perspective points to the remarkable trajectory of human development. The same evolutionary period that produced disease resistance and dietary adaptations also enabled advanced abstract reasoning, complex language, sophisticated cooperation, science, art, and extended lifespans. These outcomes seem to represent genuine progress toward a "better" state of human existence.

Proponents argue that traits like deep empathy, artistic expression, and advanced reasoning may not have offered immediate survival advantages in early agricultural villages, yet they persisted and flourished. Their prevalence suggests selection for something beyond mere survival—perhaps an inherent human potential or purpose that evolution was unconsciously fulfilling.

This theory faces the devastating critique of the naturalistic fallacy. Just because evolution produced certain outcomes doesn't make them morally "good." Evolution also produced parasites, predation, and extinction. The definition of "good" remains entirely subjective and culturally contingent. Using evolutionary outcomes to define moral goals is circular logic—we select the results we prefer and declare them the intended destination.

Moreover, this view ignores the contingent nature of our evolutionary path. Different environmental pressures or random events could have led to vastly different biological and societal outcomes. There was no destined "good" endpoint, and attributing purpose to a blind, amoral process projects human meaning onto mindless natural selection.

The Convergent Pull: Same Traits, Different Reasons

Despite their philosophical differences, both theories lead us to the same practical conclusion. They both compel us toward selecting for remarkably similar traits, though for different reasons.