Why Some Populations Are Taller

The variable missing from most height explanations

Most people have the right intuition about height: better nutrition and better childhood health make people taller. Over the last century, as living standards improved, average stature rose across much of the world, and in several rich countries it continued rising well into the late 20th century.

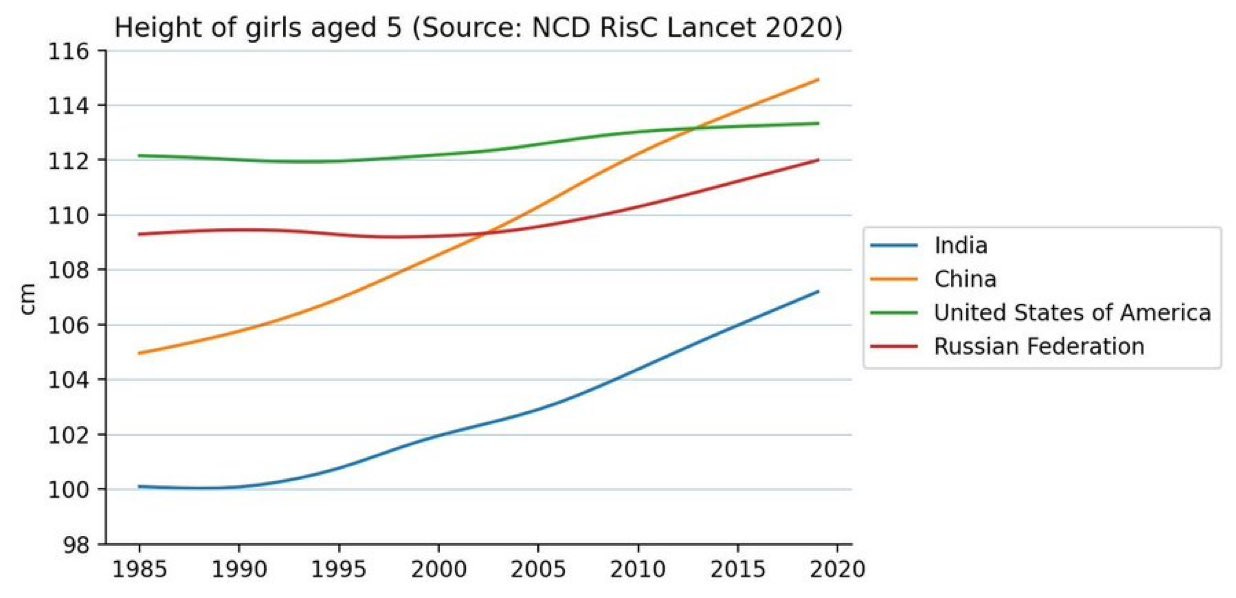

A concrete way to see environment at work is to look early in life. The figure below plots average height at age 5 for girls in China, India, the United States, and Russia across time. China is the key case: Chinese girls were once shorter in this comparison, then gained rapidly and now sit near the top. Such changes cannot be genetic on a generational timescale. They reflect improvements in childhood conditions—nutrition, disease burden, sanitation, and healthcare. This focus on early childhood is deliberate. Twin studies shows that the heritability of height increases with age, while environmental influences are strongest in infancy and early childhood (Jelenković et al. 2016). As a result, height at age 5 is a useful proxy for population-level environmental conditions, before the genetic contribution to adult stature fully expresses itself. China’s catch-up is also consistent with dramatically improved living standards and protein intake, helped by relatively cheap calories and a low birth rate that made it easier for families to invest in child growth.

So far, most public discussion of global height differences has been built on cross-sectional correlations: countries with higher GDP, higher protein intake, and lower infant mortality tend to be taller. That evidence is real, but it leaves out a variable that matters a lot for height.

That variable is genetics.

Adult height is highly heritable within populations (twin and family studies typically put adult height heritability around 80–90% in Western samples), which means genetic differences explain a large share of why people differ in height inside the same cohort.

The key question, then, is not whether nutrition matters. It clearly does. The question is whether between-population height differences are purely environmental, or whether part of the gap reflects differences in genetic predisposition as well.

In our paper, we test this directly by adding polygenic scores for height to the usual living-standards predictors across dozens of populations (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024).

The missing variable: genetic predisposition for height

In economic history and development research, height is often treated as a proxy for living standards, implicitly assuming that populations are genetically interchangeable for stature. Our paper makes the basic point directly: using height as a development indicator across populations relies on a “blank slate” assumption about genetic potential that may not hold.

To address this, we add genetic data in the simplest workable way: polygenic scores (PGS), which summarize thousands of trait-associated variants into a single index of genetic predisposition.

What we analyzed

Genetic data: whole-genome sequencing for 51 populations, plus a larger dataset combining WGS and array data for 89 populations.

Height genetics: multiple PGS built from different GWAS designs, including a multi-ancestry GWAS PGS (MIX-Height) and a within-family sibship GWAS PGS (SIB-Height).

Environment and living standards: Human Development Index (HDI), calories, protein supply, infant mortality, wasting, and related indicators.

Phenotype (observed height): primarily from the large NCD-RisC meta-analysis, with additional sources for subregions not covered.

Genetics and environment both matter, and the best model uses both

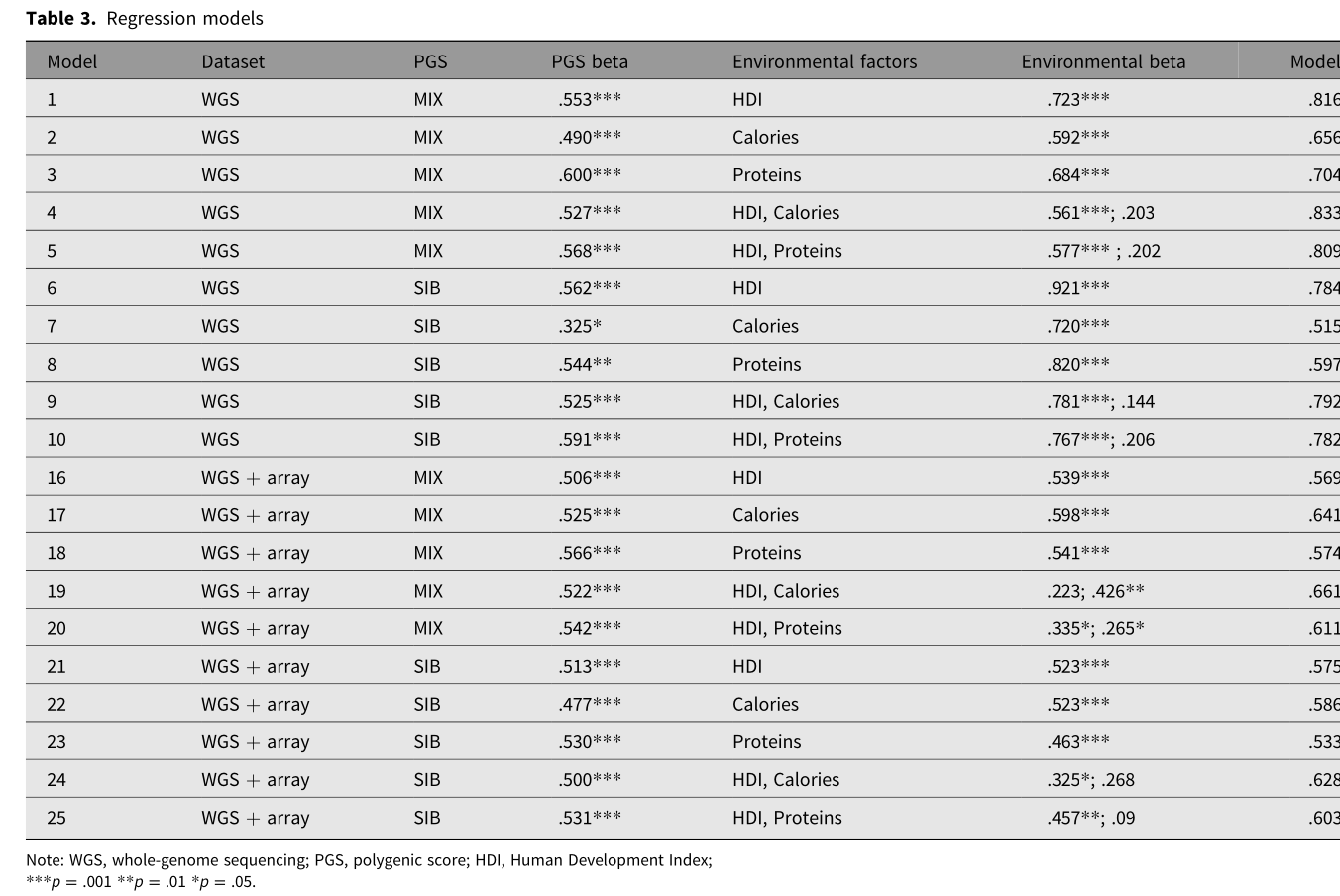

Tables 3–5 show how height PGS and living-standard variables behave into the same regressions, so it is possible to see whether each adds anything once the other is already in the model.

As shown in table 3, across both PGS constructions (MIX and SIB) and across both datasets (WGS-only vs WGS+array), two patterns repeat.

First, the PGS coefficient is consistently large, and it remains large even when the model includes HDI, calories, or protein supply. Second, combining genetics with a living-standard measure typically yields the highest fit.

The mixed WGS+array dataset has lower overall R² than WGS-only, but the qualitative pattern is the same: genetics contributes a lot, and environmental variables still help.

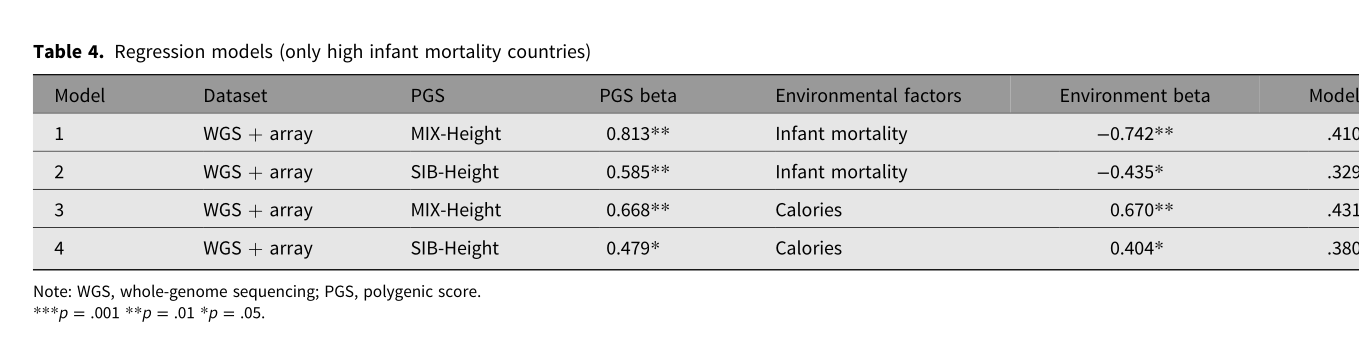

In high infant-mortality settings, constraints show up clearly

When we restrict the sample to countries with high infant mortality, environmental conditions exert a strong negative effect on height, while the polygenic score remains positively associated with stature. In other words, even in harsh environments that substantially depress growth, genetic differences continue to predict who is taller and who is shorter (Table 4 below).

Calories also predicts height in this group, but infant mortality appears to capture a broader dimension of early-life conditions, encompassing disease burden and overall developmental stress rather than nutrition alone.

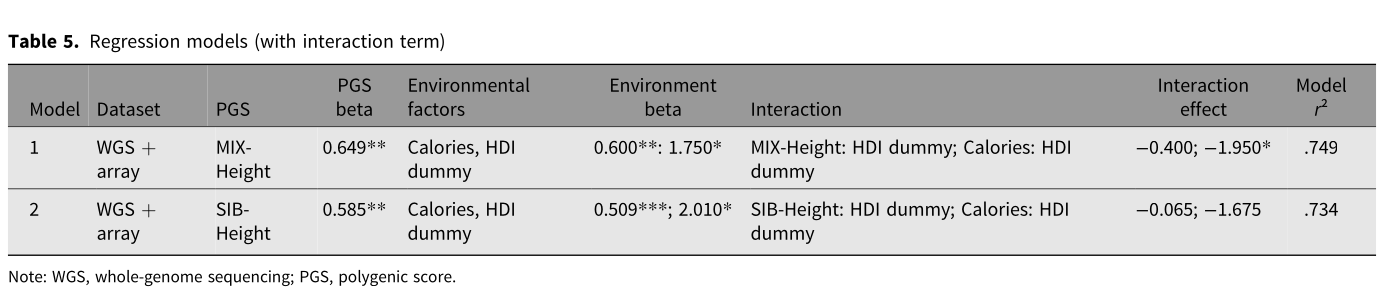

Calories matter less once development is high

To test whether these relationships change once countries reach high development, we then introduced an HDI dummy and interaction terms. The key pattern is clear (Table 5 below): the calories × high-HDI interaction is negative, indicating that calories are strongly predictive at low levels of development but much less informative once countries enter the high-HDI regime.

The “African paradox”: tall stature despite poor childhood conditions

Angus Deaton (2007) - a Nobel laureate in Economics - famously highlighted what he called an “African paradox”: some African populations are relatively tall despite poorer childhood health and nutrition than much richer countries. He saw it as a paradox because he grossly underplayed the importance of genetics due to his own biases. But once genetic differences are taken into account, the paradox resolves.

He also found that the environment didn’t predict height differences in high infant mortality countries. We found the opposite:

Among populations with high infant mortality, both genetic scores and environmental measures still matter, and the tall stature can be partly attributed to a higher genetic predisposition for height.

This runs against the idea that genetics is irrelevant in low-income/high-mortality settings, or that nutrition/health stop predicting height there.

Is there evidence of selection on height-related variants?

Are cross-population differences in height genetics roughly what neutral drift would produce, or are they unusually large?

To get at that, we used two standard tests.

QST–FST comparison

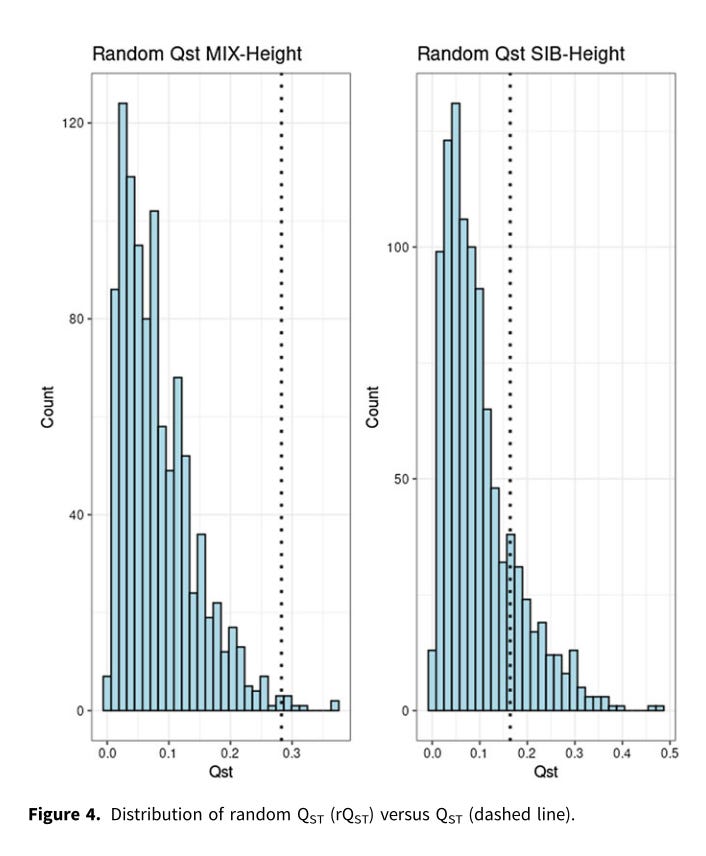

We wanted to test whether the cross-population differences in height genetics look like what neutral drift would produce. The idea is simple: compare how differentiated the height PGS is across populations to how differentiated “neutral” loci are. QST is the between-population divergence of a trait-like measure (here, the height PGS), while FST summarizes genome-wide neutral differentiation. If the PGS is more differentiated than neutral markers, that pattern is consistent with divergent selection rather than drift alone.

In our QST–FST analysis, the QST/FST ratio is above 1 for both MIX-Height and SIB-Height, but only MIX-Height reaches significance (Monte Carlo p ≈ 0.008; SIB-Height p ≈ 0.179). A complementary test provided similar results. When we compare FST at height GWAS loci to neutral loci, the enrichment is significant for MIX-Height (p < 0.001) but not for SIB-Height (p ≈ 0.10).

The large, multi-ancestry PGS shows clearer signals consistent with selection tests in these datasets. The within-family PGS looks weaker because it’s an intrinsically harder signal to estimate: siblings don’t differ that much genetically, so within-family GWAS has less variance to work with, on top of smaller sample sizes.

Conclusion

The main result is straightforward: models that treat height as purely environmental are leaving explanatory power on the table. When genetic height scores are included alongside living-standard measures, both terms remain important, and the combined models explain substantially more of the cross-population variation in adult stature.

This changes how height should be used in cross-country comparisons. Average height is not a clean thermometer for “living standards” in the way it is often treated in economic history and development work. It reflects early-life conditions, yes, but also genetic differences in height predisposition across populations. Once both are in the model, persistent height gaps look less mysterious, and paradoxes are resolved.

References

Deaton, A. (2007). Height, health, and development, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (33) 13232-13237, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0611500104

Jelenkovic, A., Sund, R., Hur, YM. et al. (2016). Genetic and environmental influences on height from infancy to early adulthood: An individual-based pooled analysis of 45 twin cohorts. Sci Rep 6, 28496. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28496

Piffer D, Kirkegaard EOW (2024). Polygenic Selection and Environmental Influence on Adult Body Height: Genetic and Living Standard Contributions Across Diverse Populations. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(6):265-282. doi:10.1017/thg.2024.43