Human–Chimp DNA Similarity: 99%, 95%, or 85%?

TL;DR

The familiar claim that humans are about 99% chimpanzee is based on a real measurement, but it applies only to a narrow type of comparison. It usually means ~98–99% identity for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in DNA regions that align cleanly.

It gets repeated as if it described the entire genome, but whole genomes differ not only by SNVs. They also differ a lot by insertions/deletions, duplications, inversions, and repeat-rich regions that often do not align one-to-one.

When you include those harder regions and ask a stricter question, the fraction of bases with an exact one-to-one match can drop to roughly ~84–85% on autosomes in telomere-to-telomere era comparisons.

The scythe of egalitarianism and blank-slatism does not stop at human differences. It also likes to erase differences between humans and other primates. That is why the claim “humans are 99% chimpanzee” is repeated so often. It sounds authoritative, scientific, and final. It reassures people that biological differences are tiny and therefore unimportant.

Humans and chimpanzees really are genetically close. What gets distorted is the meaning of the famous percentage. The 99% figure comes from a limited, alignment-based comparison, yet it is often repeated as if it described the entire genome.

The slogan is not confined to casual internet memes. Museums and major science outlets routinely repeat versions of it. For example, the American Museum of Natural History asks: “If human and chimp DNA is 98.8 percent the same, why are we so different?” and National Geographic states that chimpanzees share 98.7 percent of our genetic blueprint.

Where the 99% figure actually comes from

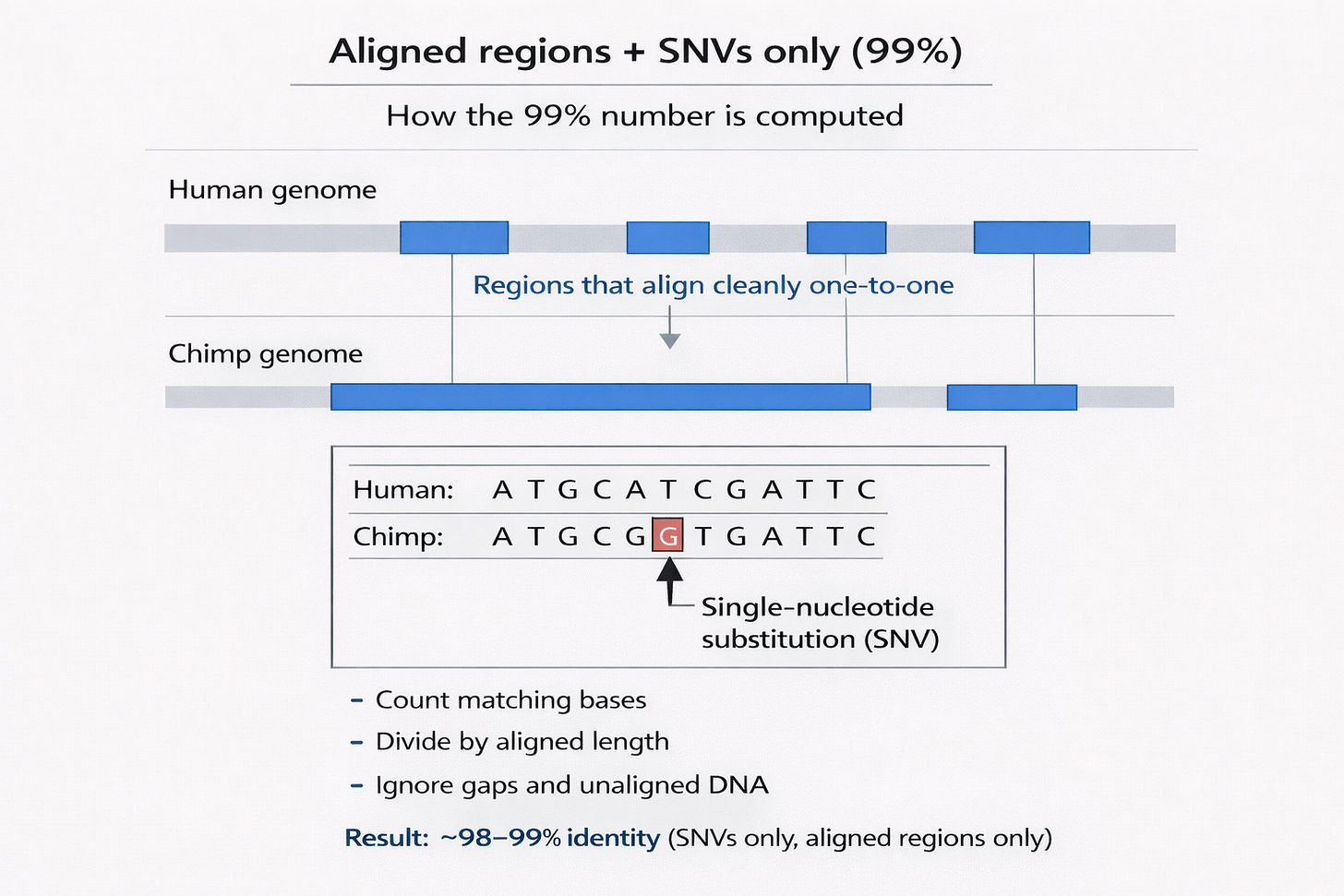

The famous number comes from a very specific type of comparison.

Researchers take the parts of the human and chimpanzee genomes that can be aligned cleanly, meaning stretches of DNA where you can line up one base in humans with one base in chimps. Within those aligned regions, they count only single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), which are one-letter differences in DNA. For example, humans might have an A at a given position while chimps have a G, or humans have a C where chimps have a T.

When you count only these one-letter differences within aligned DNA, humans and chimps differ by roughly 1.2 to 1.6 percent, which implies 98 to 99 percent identity by this definition. This substitution-based estimate was reported in the landmark chimp genome comparison paper and has been broadly consistent across later analyses that use similar alignment-based methods (The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005).

The figure below illustrates how this “~99%” number is computed: it is a base-by-base identity calculation restricted to regions that align cleanly one-to-one, where most positions match and occasional single-nucleotide substitutions (SNVs) account for the remaining difference

What this number tells us is simply that in conserved, alignable DNA, humans and chimpanzees are extremely similar. However, it does not tell us how similar the entire genome is.

Insertions and deletions

Single-letter substitutions are only one way genomes differ. Large parts of the difference between species come from insertions and deletions, where chunks of DNA exist in one genome but not in the other.

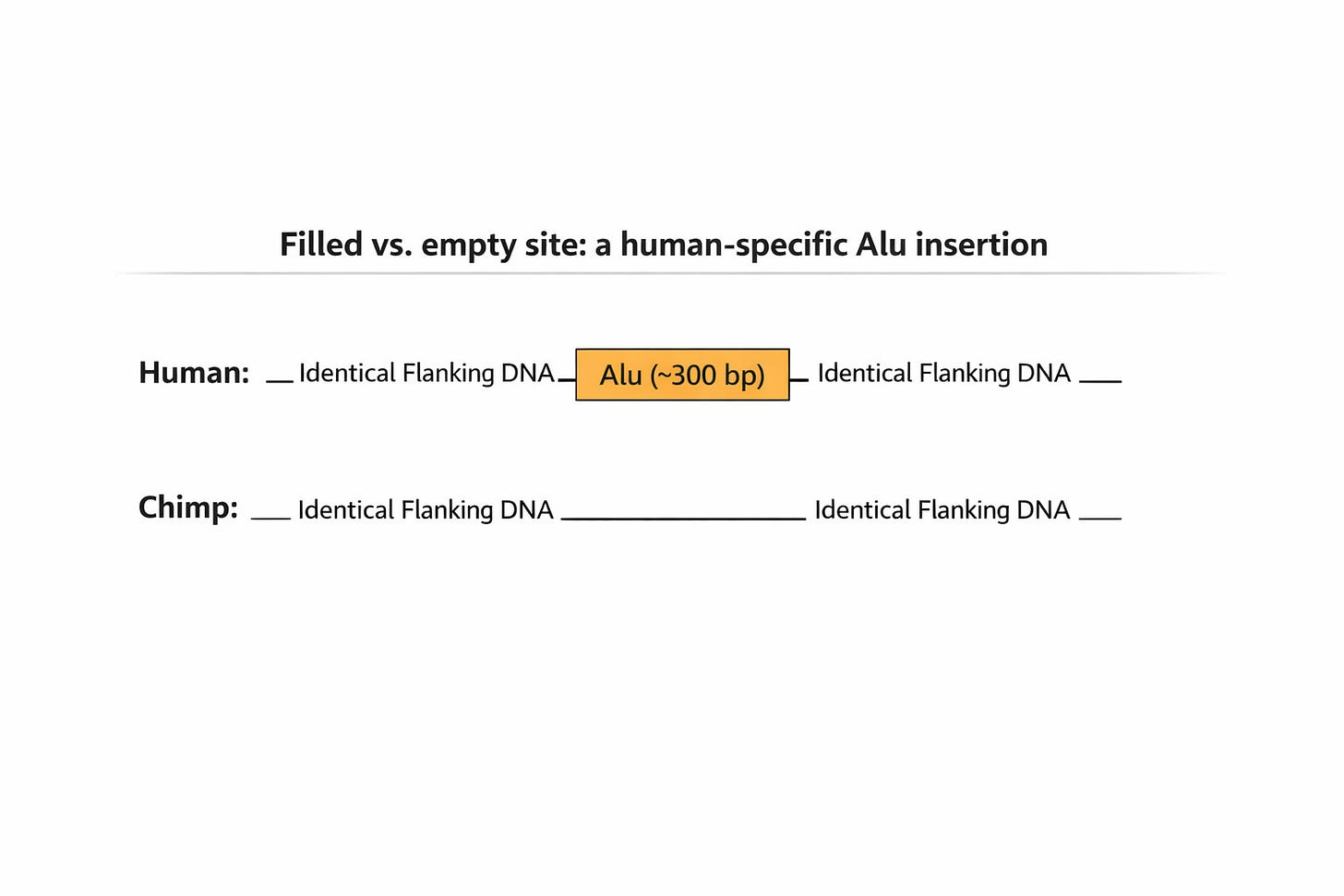

A concrete example is the PV92 locus on human chromosome 16. At this position, many humans carry an insertion of an Alu element, a short mobile DNA sequence about 300 base pairs long. The orthologous region in chimpanzees lacks this sequence entirely and represents the ancestral “empty site.” The DNA flanking the insertion aligns cleanly between species, but the inserted segment itself has no one-to-one counterpart in the chimp genome.

Cases like PV92 are common. Thousands of human-specific insertions, many involving mobile elements such as Alu or LINE-1, are present in the human genome but absent at the corresponding locations in chimpanzees. Depending on the method, these regions are either treated as gaps, heavily penalized, or excluded altogether from similarity calculations.

The figure below illustrates this point schematically, showing how cleanly aligned flanking regions coexist with insertions that break simple base-by-base alignment.

When indels are included, divergence rises substantially. As early as 2002, Roy Britten showed that once you count indels alongside substitutions, divergence in sampled human–chimp comparisons rises to around 5 percent, implying about 95 percent similarity, not 98 percent (Britten, 2002).

Already at this stage, the famous number depended on what you chose to count.

Structural omissions

The bigger omission is structural. A significant fraction of the genome simply does not align neatly between humans and chimps. This includes duplicated regions, rearrangements, inversions, repeat-rich areas, centromeres, and telomeres.

Earlier genome assemblies were incomplete and biased toward regions that aligned well to the human reference. That bias inflated similarity estimates by construction. If a region could not be aligned, it was often excluded from the calculation entirely.

This is where modern genomics changes the picture.

What changed in 2025

In 2025, a major Nature paper finally delivered complete telomere-to-telomere assemblies for multiple ape genomes, including chimpanzee (Yoo et al., 2025).

These assemblies resolve regions that were previously missing or collapsed, especially repetitive and structurally complex DNA. For the first time, humans and chimps can be compared without pretending that large parts of their genomes do not exist.

Several facts are now clear.

First, SNV divergence in alignable regions is still about ~1.5%, so the familiar 98–99% identity remains accurate for that narrow metric.

Second, whole-genome comparison is harder because a substantial fraction of sequence does not map cleanly one-to-one between the species. Depending on the method, roughly 12–13% of human sequence has no simple one-to-one counterpart in chimpanzee, largely because of duplications, indels, and other structural rearrangements.

If you instead ask the stricter question, “What fraction of bases have an exact one-to-one match?”, the estimate drops to roughly 84–85% on autosomes. This is the telomere-to-telomere lesson: the classic number survives, but it applies to a filtered subset of the genome.

What about non-coding DNA?

Non-coding DNA makes up about 98 percent of the genome, and it is often treated as if it were either irrelevant or wildly divergent. Neither is correct.

For single-nucleotide substitutions, non-coding regions that can be aligned show divergence rates similar to the rest of the genome, around 1.4 to 1.6 percent. Coding regions are slightly more conserved because of stronger purifying selection, but the difference is modest.

The dramatic drop in global similarity does not come from an explosion of point mutations in non-coding DNA. It comes from structural variation, including indels, duplications, and lineage-specific sequence.

Calling this DNA “junk” misses the point. Many of these regions are regulatory.

Small sequence differences can matter a lot

Even if you focus only on SNVs, it does not follow that small percentages imply small biological effects.

Single-nucleotide changes in promoters, enhancers, or transcription factor binding sites can shift gene expression in specific tissues or developmental stages. Copy number changes can alter dosage. Regulatory networks can amplify small upstream changes into large phenotypic effects.

That is why humans and chimps can be very close at the level of aligned sequence while still being very different organisms.

A precise statement would be something like this:

Humans and chimpanzees are about 98 to 99 percent identical for single-nucleotide substitutions in the parts of the genome that align cleanly. When insertions, deletions, and structurally complex regions are included, similarity is lower. With complete genomes, the fraction of bases that match one to one across the entire genome is closer to the mid-80 percent range, depending on how similarity is defined.

Conclusion

The 99% percent claim survives because it is rhetorically useful. It compresses a complicated reality into a comforting number. But genomes are not compared by slogans.

Humans are not “basically chimps” plus a rounding error. We are closely related primates whose genomes differ in subtle ways in conserved regions and in substantial ways in structure and regulation.

References

R.J. Britten (2002).Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels,Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.99 (21) 13633-13635,https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.172510699

The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. (2005). Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature, 437, 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04072

Yoo et al., (2025). Complete sequencing of ape genomes, Nature 641:401–418. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08816-3.

That's one nifty algorithm right there: "Let's align the DNA blocks so they fit nicely, and then let's celebrate they indeed fit 99% nicely." :)

Always wanted to know what that number meant, thank you.