Intelligence Isn't Really Sexy

Evidence From Dating Apps, Experiments, and Genetics

TL;DR

Recent research overturns a core claim in evolutionary psychology: that intelligence is a strong sexual attractor.

Speed-dating & lab studies: Intelligence is detectable but doesn’t boost sexual appeal; attractiveness dominates.

Dating app data: Intelligence has a tiny positive effect, but it’s ~7× weaker than looks; no sex differences.

Population genetics: Higher intelligence and education predict greater risk of lifelong sexlessness.

Big picture: Intelligence may aid long-term compatibility and parenting, but in initial mate choice, it is not a decisive attractor. Looks and social traits win.

The Puzzle

There’s a puzzle at the heart of human mating psychology. Evolutionary psychology textbooks confidently assert that intelligence is a key female mate preference. Surveys support this: when asked, women consistently say they want clever, accomplished partners. Yet a growing body of empirical evidence suggests something more complex is happening in actual mating contexts.

In the past few years, multiple studies using different methods—speed dating experiments, dating app analyses, and population-level genetic data—have converged on a surprising pattern. While intelligence does have a small positive effect on mate appeal in controlled settings, this effect is dramatically weaker than the impact of physical attractiveness. And at the population level, higher intelligence paradoxically predicts worse mating outcomes, not better ones.

The Direct Evidence: Lab and Field Experiments

In 2021, Driebe and colleagues tested whether intelligence translates into sexual appeal in face-to-face contexts. Using both speed-dating sessions and video-clip ratings, they found that intelligence was accurately perceived—smarter people were correctly identified as such—but this perception didn’t boost their appeal. The effect was slightly negative, though small.

What did matter was humor. Men who were funnier were judged more appealing, but humor wasn’t correlated with general intelligence. Physical attractiveness, meanwhile, dominated everything else. Each unit increase in attractiveness boosted sexual appeal by 1.15 units—a massive effect dwarfing all other factors. Attempts to signal intelligence (like reading newspaper headlines) only helped if the person was already physically attractive.

Online Dating in the Real World

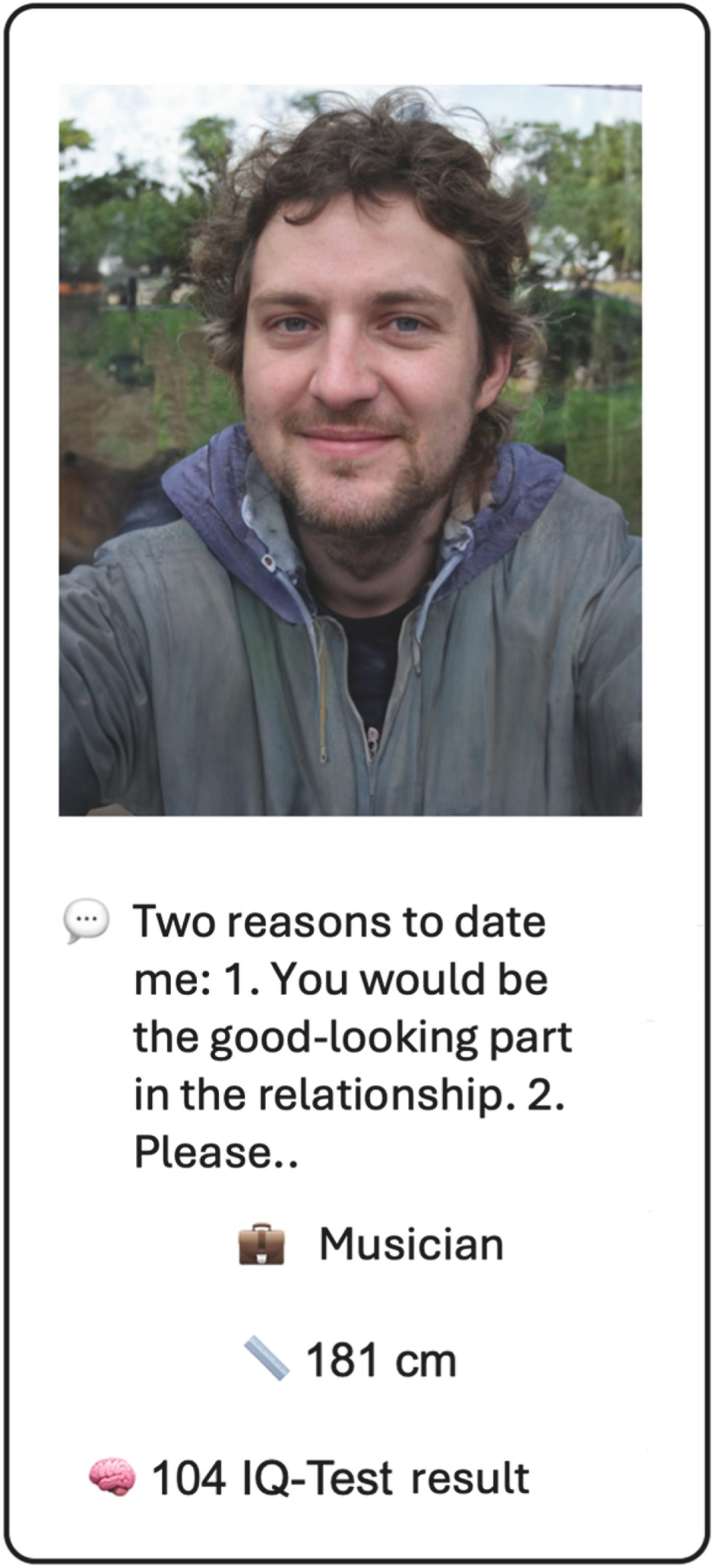

A 2025 study by Witmer, Rosenbusch, and Meral brought these findings into the modern dating landscape. Instead of using real profiles, the researchers constructed synthetic ones. Each profile combined an AI-generated photo (from This Person Does Not Exist and Ideogram) with attributes like height, occupation, and a short biography (adapted from anonymized Tinder texts).

To test the effect of intelligence, some profiles also displayed a verified IQ score between 80 and 120. These numbers were fictional but presented as if they came from an app feature. This allowed the researchers to isolate the impact of “showing intelligence” on mate choice, without relying on self-report.

Participants made over 5,000 actual swiping decisions on these controlled profiles, enabling a causal test of multiple features: physical attractiveness, height, occupation, biography quality, IQ score, and similarity to the viewer.

The results were unambiguous. Physical attractiveness had by far the strongest effect (β = 0.80). Intelligence did have a positive influence (β = 0.12)—importantly, not a negative one—but its impact was roughly seven times smaller. Biography quality (β = 0.11) and height (β = 0.05) also mattered slightly, while occupation was essentially irrelevant.

Perhaps most striking: there were no sex differences. Men and women prioritized these traits in the same way, directly contradicting the familiar evolutionary psychology narrative that women uniquely value intelligence and resources while men chase beauty.

The study also found evidence for homophily—people were slightly more likely to swipe right on profiles similar to themselves in intelligence (β = 0.08), attractiveness (β = 0.06), and height (β = 0.06). But these similarity effects were modest compared to the raw impact of attractiveness itself.

Homophily vs. Assortative Mating: Why the Gap?

These small homophily effects help explain why intelligence shows assortative mating in established couples (correlations of 0.3–0.4) despite mattering so little at first contact. But first, it’s crucial to clear up a common misconception.

A frequent mistake is to conflate assortative mating with a preference for “more” of a trait, for instance, assuming women want men who are smarter or taller than average. In reality, assortative mating and homophily are about similarity, not superiority. People tend to end up with partners who resemble them, not necessarily partners with “more” of some trait.

The key to understanding assortative mating is recognizing that it doesn’t primarily emerge from initial attraction. Instead, it’s largely a product of structured social environments.

People meet in stratified settings—schools, universities, workplaces—that already cluster individuals by education and ability. Within those constrained pools, relationships are more likely to form and persist when partners are similar. The modest homophily observed at the swipe level gives similarity a small push, but assortative mating in long-term couples is magnified by years of structured interaction, not initial mate choice.

Beyond the Lab: Sexlessness in the Real World

One might object that lab studies and dating apps don’t capture long-term relationship formation, where intelligence might matter more. But a 2025 paper in PNAS by Abdellaoui and colleagues extends the evidence to real-world reproductive outcomes—and reveals something harder to dismiss.

Analyzing data from nearly 400,000 UK Biobank participants plus an Australian sample, they investigated correlates of lifelong sexlessness (never having had a sexual partner). Their findings were stark: sexlessness was positively associated—both phenotypically and genetically—with higher educational attainment and intelligence.

People carrying alleles linked to higher IQ were more likely to end up sexless. This is precisely the opposite of what we’d expect if intelligence functioned as a powerful sexual ornament. Even if intelligence doesn’t actively attract mates, we might expect it to buffer against sexlessness by compensating for other disadvantages. The fact that it doesn’t—that it’s actually associated with increased risk—suggests intelligence is simply not operating as a significant positive force in the mating market.

The authors are appropriately cautious, noting that these correlations are complex and culturally mediated. But from an evolutionary fitness perspective, lifelong sexlessness is an ultimate dead end. The alignment of higher intelligence with increased risk of this outcome is difficult to square with the notion that brains function as powerful courtship displays.

Glasses as a Case Study in Looks vs. Brains

Up to this point, we’ve seen that intelligence has surprisingly little direct appeal in the mating market. But one of the most striking findings comes next: why something as mundane as wearing glasses in childhood predicts lifelong sexlessness — and what this reveals about the trade-off between looks and brains. I will also discuss the implications for dysgenic fertility.