Is Italy's Native Population Being Replaced?

How collapsing native births, immigration and mixed families are reshaping the cradle.

Over the last quarter century Italy has gone from a country where almost every newborn had two Italian parents to one where a growing share of babies has at least one foreign parent. At the same time, the total number of births has collapsed.

Debates about “population replacement” usually focus on immigration. But if you look at the data, the story is more complicated and, in some ways, more unsettling: a sharp fall in births to two Italian parents, a rise (and then partial decline) in births to two foreign parents, and a steady, persistent increase in children born to mixed Italian–foreign couples.

In this post I walk through ISTAT birth statistics by parental citizenship from 1999 to 2024 and show how these trends fit together. The charts later on make the pattern hard to ignore: Italy is not being transformed by one sudden wave, but by the combination of native collapse, immigration, and the quiet growth of mixed families.

1. What the data measure

The ISTAT tables classify births in four groups, according to the citizenship of the parents:

Both Italian parents

Both foreign parents

Italian father, foreign mother

Foreign father, Italian mother

In the third and fourth plots I keep all four groups. In the first two plots I merge the two mixed categories into a single group called “Italian + foreign parent”.

Note that this is a classification by citizenship of the parents, not by “ethnicity” of the child. Many children born to foreign parents will later become Italian citizens. So when I use shorthand like “native” I am really referring to births to two Italian-citizen parents.

What comes next is the part people argue about: the actual numbers, the curves, and the demographic shifts nobody shows in public debates.

If you want to see the full breakdown, the charts, and the implications, unlock the rest below.

2. The shrinking majority

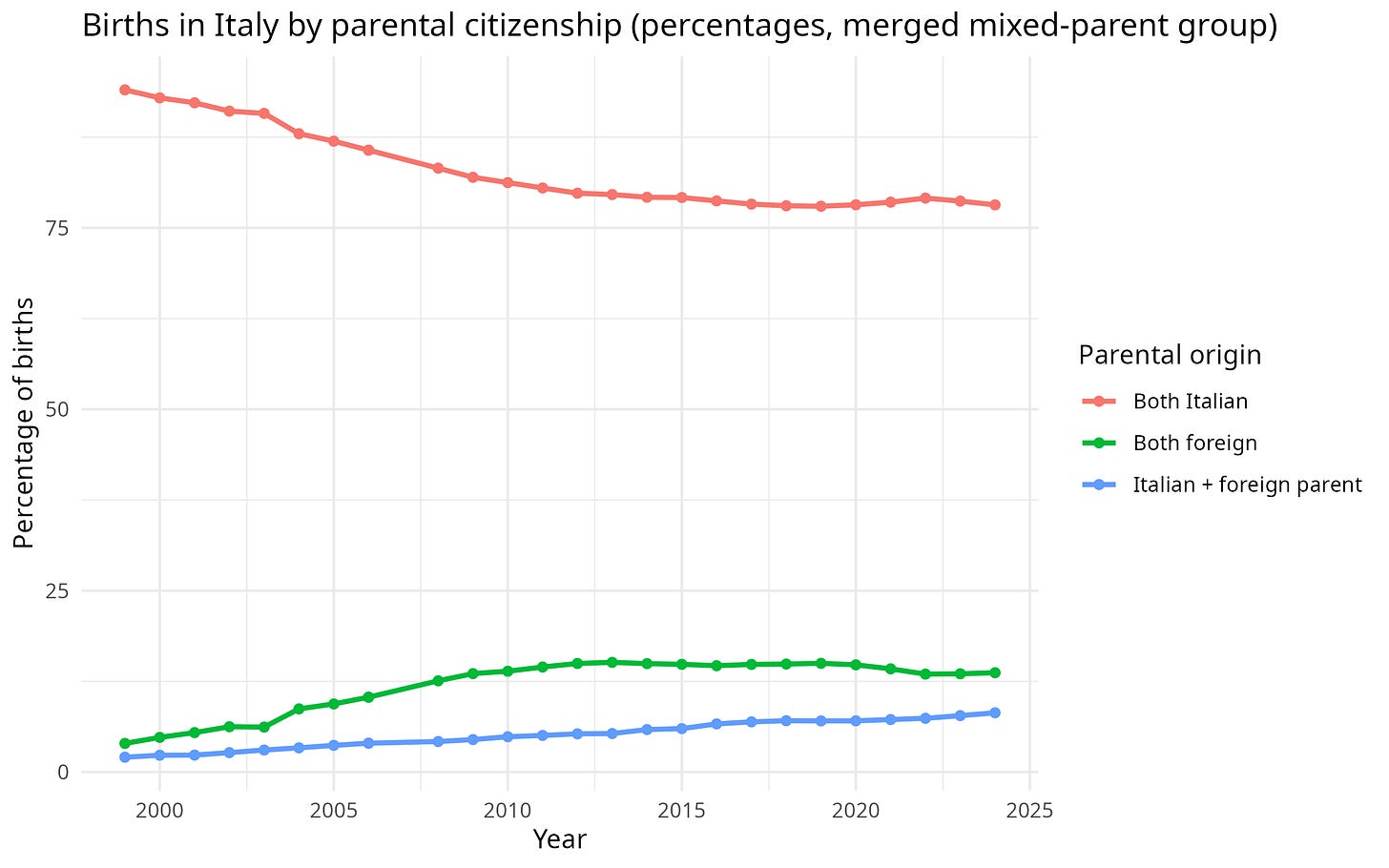

Look at Figure 1 (percentages, merged mixed group).

In 1999, births with two Italian parents are above 90% of the total.

Their share then falls almost every year until around the mid 2010s, and stabilises around 78–80%.

Figure 1.

So the majority is still large, but clearly shrinking. Even if the line has flattened recently, it is about ten to twelve percentage points lower than at the start of the series.

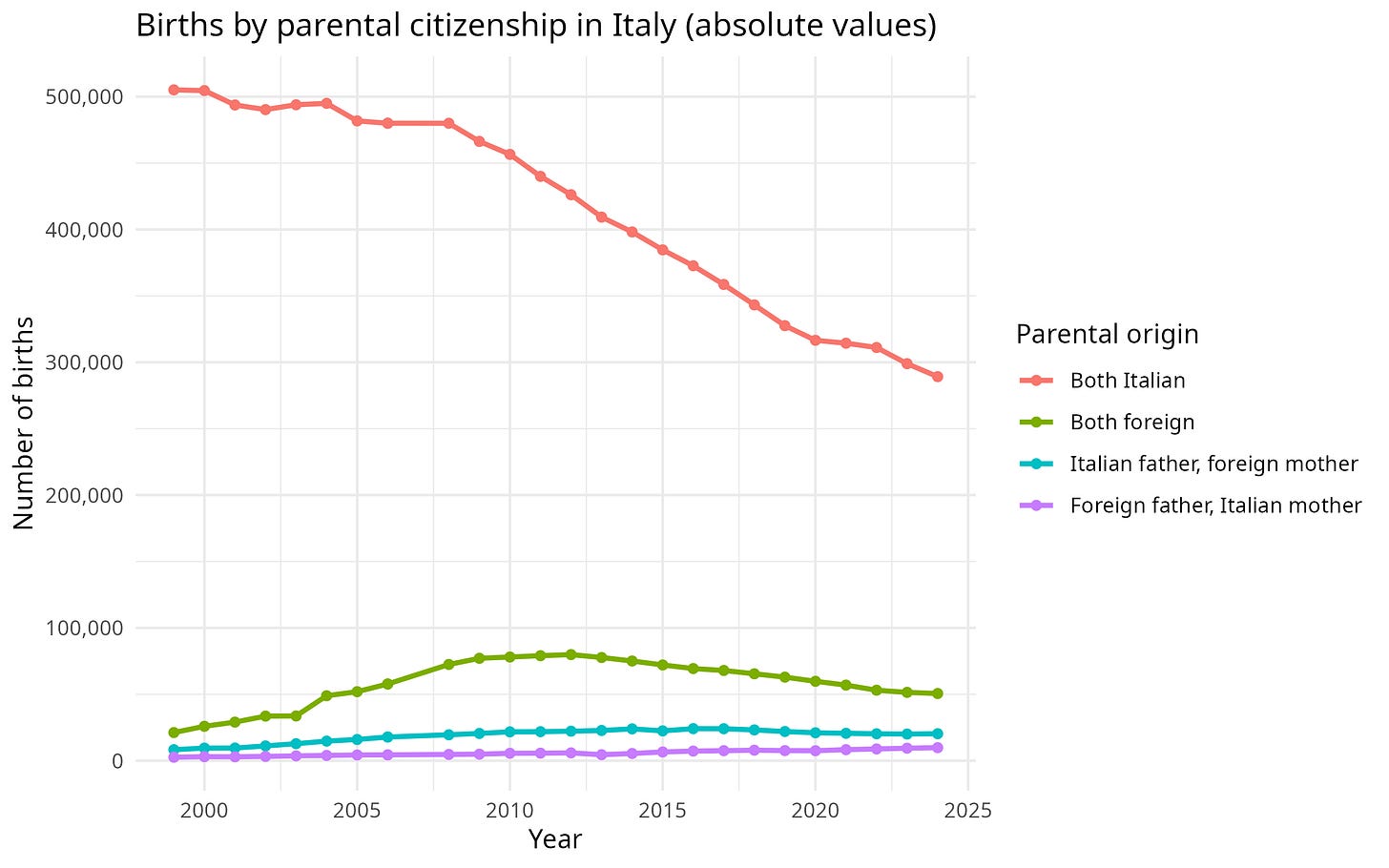

The same pattern appears in absolute numbers in Figure 2.

Births to two Italian parents decline from just over 500 thousand in the late 1990s to under 300 thousand today.

This is a drop of roughly 40% in a single generation.

Figure 2.

The “slow replacement” is therefore not only relative. It is also absolute. There are far fewer Italian-Italian births than twenty-five years ago.

Why the red line drops faster in levels than in percentages

One thing that can be confusing in these charts is that the absolute number of babies with two Italian parents collapses, while their percentage among all births falls more gently.

The reason is simple: it’s not only Italian–Italian births that are going down – total births are going down.

At the end of the 1990s Italy had a little over half a million babies a year with two Italian parents, plus a relatively small number from mixed and foreign couples. Today there are far fewer babies with Italian parents, but there are also fewer births overall. Mixed and foreign births softened the decline a bit, especially in the 2000s, but they never became large enough to offset the collapse of native births, and they too started to fall after 2010.

In absolute terms, the collapse is brutal: there are hundreds of thousands fewer Italian–Italian babies than a generation ago.

Italian births were collapsing in percentage terms before 2010 because foreign births were rising; after 2010 foreign births stopped rising and began falling too, so the Italian percentage stabilized.

3. Foreign parents: rise, peak, and retreat

In the same figures, the green line shows births where both parents are foreign citizens.

In 1999 they are a small minority of births, around 4–5% of the total.

Their share climbs steadily for more than a decade, peaking around 15% in the early 2010s.

After that peak it declines slightly and seems to settle around 13–14%.

In absolute terms the story is similar.

Foreign-foreign births rise from about 20 thousand to almost 80 thousand at the peak.

Since then they have fallen back to roughly 50 thousand.

This pattern fits what we know from immigration flows. The big wave of immigration into Italy happened in the 2000s. Fertility among recent immigrants tends to be high at first, then converges downward, both because the first cohorts age and because their fertility norms move closer to the host country. I have analyzed this process in a previous post:

The curves of the foreign-foreign group show exactly that: a wave that swells, crests, and begins to recede.

4. Mixed couples: the quiet but steady climb

The blue line in the first two figures represents births with one Italian and one foreign parent, merging both directions (Italian father + foreign mother and foreign father + Italian mother).

Here the story is different.

In percentage terms, the mixed-parent share starts at about 2–3% at the end of the 1990s.

It rises almost monotonically and reaches 8–9% by the early 2020s.

In absolute numbers, mixed births grow from around 10 thousand to well over 30 thousand. There is no clear sign of a peak yet.

Figures 3 and 4, which split the mixed category into the two directional pairings, add some nuance.

Both types of mixed couple become more common over time.

If we split the mixed group into the two directions – Italian father + foreign mother versus foreign father + Italian mother – an extra pattern appears.

Across the whole period, births with an Italian man and a foreign woman are clearly more common than those with an Italian woman and a foreign man. Both lines rise over time, but the “Italian father / foreign mother” line is always on top.

This tells us something about how integration actually works on the ground:

Italian men are more likely to form families with foreign women than Italian women are with foreign men.

Italian women, on average, still tend to have children with Italian partners.

A good share of “foreign origin” in the next generation is therefore coming via foreign mothers joining Italian men, not only via immigrant couples where both parents are foreign.

So the mixed-parent group is not just a neutral bridge category. It reflects a gendered pattern of partnership: foreign women are integrated into Italian family networks faster than foreign men are, and Italian men are the main “gateway” for that assimilation route.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The important point is that mixed unions are the most steadily growing component of the system. Even as births to two foreign parents start to plateau or decline, births to Italian–foreign couples keep increasing.

This is exactly what you would expect in a country that has moved from “new immigration” to “settled immigration”. First you see a rise in foreign–foreign couples as migrants marry within their own communities. Then, as years pass, you see more unions across citizenship lines.

5. A slow, uneven transition

Taken together, the four plots show a slow transition from a homogeneous birth structure to a more mixed one.

The native core is shrinking in both relative and absolute terms.

The foreign-born fringe expanded quickly, then slowed down.

The mixed middle is low but slowly and steadily growing, knitting the two together.

It looks less like population replacement, and more like a slow-motion melting pot.

Yes, it appears that Italy and most other European countries are intent on destroying their culture. But most people aren't very bright!