Brain Drain Is Mostly a Myth. The Real Problem Is Who Comes Back.

And the Slow Disappearance of Italy’s Native Population

1. What people get wrong about brain drain

Every year Italian media has been running the same headline for several decades: we are losing our best brains. The phrase “brain drain” (“fuga di cervelli”) is used as if it was a simple, self-evident fact. More graduates leave, therefore Italy is bleeding human capital.

This is exemplified by this recent Tweet, showing a seeminly catastrophic increase in the number of people with university degrees who emigrated:

But “brain drain” actually has a standard meaning:

Brain drain = emigration of highly trained or qualified people from a country.

Even this definition is not enough if you look only at a single raw number. At least two things are missing:

It ignores the emigration of low-educated citizens, which can raise average human capital at home.

It ignores returns: Italians who leave and later come back.

In this article I focus entirely on Italian citizens. The ISTAT data I use (Tavola 12) track:

Italian citizens who leave Italy and move abroad (outbound), and

Italian citizens who return from abroad and register again in Italy (inbound).

No foreign citizens are included, either among emigrants or among arrivals. This gives a clean measure of brain drain in the strict sense: how much human capital Italy loses and regains when its own citizens move out and come back.

Immigration of foreign citizens is an important topic, but it is outside the scope of this post.

2. Who leaves, who returns

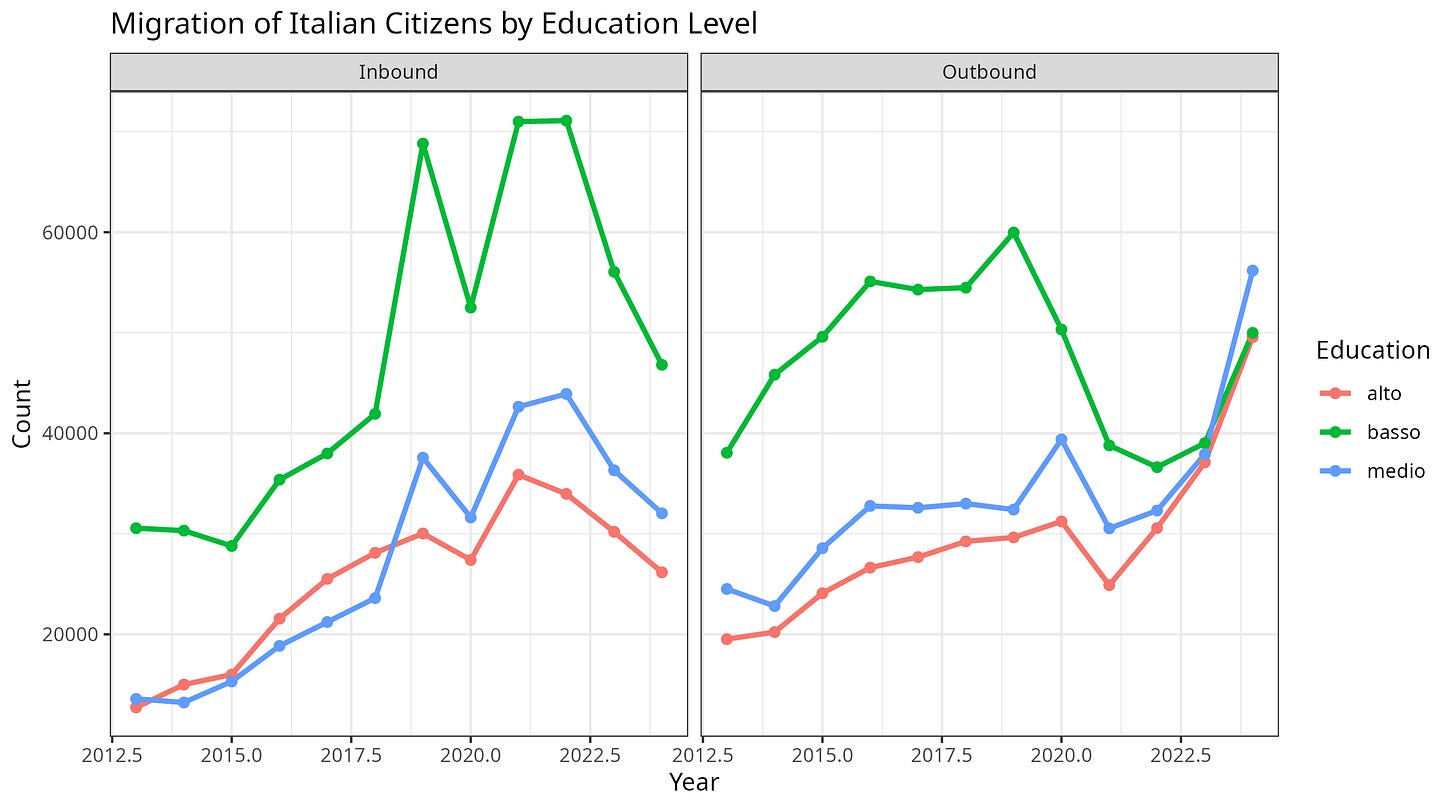

This plot shows, for 2013–2024:

Left panel: Italian citizens moving back to Italy from abroad (inbound, i.e. returns).

Right panel: Italian citizens moving out of Italy to abroad (outbound).

Colors:

Green line: low education (high school drop-outs)

Blue line: medium education (high school diploma)

Red line: high education (university degree or higher)

What you see:

Outbound flows of Italian citizens rise for all education levels. Italy exports a lot of people, not just graduates.

Low-educated Italians are always the largest group in absolute terms.

Inbound flows of returning Italians are non-trivial and involve all three education levels. Many Italians do come back, including graduates.

If you only plot the red line on the outbound side and call it “brain drain,” you are not looking at the other side of the coin. The key questions are:

Among Italian citizens, how many graduates leave compared to low-educated citizens?

Among Italian citizens, how many graduates come back compared to low-educated citizens?

For paid subscribers I unpack what “brain drain” really looks like once you compare graduates to school dropouts, adjust for the rising education of younger Italians, and then combine outbound and inbound flows into a single net “brain balance” index. The result is a very different story from the usual media panic, and it points to where Italy’s real human-capital problem actually sits.