The Four Races of Europe (Part I): The Aryan paradox

How Deep Ancestry Still Affects Us

For much of the 20th century, physical anthropologists tried to divide Europeans into a few “races” based on skull shape, stature, hair and eye color. Carleton Coon’s classic The Races of Europe (1939), for example, described Europe in terms of Nordic, Mediterranean, and Alpine types (plus a zoo of subtypes like “Dinaric” and “Atlanto-Mediterranean”).

Those schemes were based almost entirely on morphology (what people looked like) and were developed before anyone could read genomes. They mixed real population structure with a lot of guesswork and value-laden language.

Today, with tens of thousands of ancient and modern genomes, we can reconstruct Europe’s population history with far more precision. The picture that emerges is both simpler and deeper:

Most present-day Europeans are a four-way admixture of

Anatolian Neolithic farmers

Western hunter-gatherers (WHG)

Natufian / Levant–Mesopotamian–related ancestry

Pontic–Caspian Steppe herders (Yamnaya-like)

These are not “races” in the 19th-century sense of relatively stable, pure lines. They are deep ancestral populations that remained partially separated for thousands of years before mixing in the Holocene. Ancient DNA lets us actually see these lineages in time and space.

In this post I’ll:

Sketch how old racial typologies (Nordic/Alpine/Mediterranean) relate to these genomic ancestries.

Describe the four ancestral clusters recovered by ancient DNA.

Show how modern traits in Europeans still reflect these ancestries, with results from Pankratov et al. (2024) and my own analyses of ~4,000 ancient genomes.

From Coon’s “Three Races” to Four Ancestral Lineages

Coon and his predecessors worked with crania, photos and calipers, not SNP chips or whole genomes. In his 1939 book, he expanded William Z. Ripley’s tripartite classification of Europeans (Nordic, Alpine, Mediterranean) into a more elaborate typology, but the core idea remained: Europe = a few morphologically defined “races”.

Interestingly, some elements of that older picture overlap with what genomes now show:

“Paleolithic” vs “Mediterranean” types: “Coon argued that the ‘white race’ in Europe was of dual origin, arising from mixtures between robust Upper Paleolithic survivors in central and northern Europe and later, more gracile Mediterranean populations that expanded northward during the Neolithic from the Mediterranean and Southwest Asia.

Modern ancient-DNA work indeed finds that Mesolithic Western hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers from Anatolia/Near East are two of the three/four major sources of European ancestry (Lazaridis et al., 2014).

But there are also major differences:

Coon had no access to ancient genomes, so he couldn’t see the Steppe / Yamnaya input that later transformed much of Europe in the Bronze Age. That wasn’t discovered until large-scale ancient DNA studies in the 2010s (Haak et al., 2015).

His categories were phenotype-first and often subjective; modern work is built on allele frequencies and explicit population models.

Old racial typologies treated these groups as relatively stable, while we now know Europe’s history is one of continuous admixture and replacement.

So in a sense, what Coon tried to do by eye, modern genetics now does with far higher resolution, and the answer is not “Nordic vs Alpine vs Mediterranean,” but four deep ancestral sources with complex overlaps.

The Four Deep Ancestries of Europe

1. Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF)

Time: ~8,500–5,000 BCE

Region: Central and Western Anatolia

Key evidence: Early genomes from Neolithic Anatolia and Central Europe show an incoming farmer population genetically close to Near Eastern early agriculturalists (Lazaridis et al., 2014).

These farmers carried the Neolithic package of wheat, barley, goats, sedentary villages, and expanded into the Balkans and then across Europe, often replacing or absorbing local hunter-gatherers.

Today, Anatolian Farmer ancestry is especially high in:

Sardinia

Southern Italy and Sicily

Aegean Greece

Parts of Iberia

These groups are the closest living proxies to the Early European Farmers (EEF) identified by Lazaridis et al. (2014).

2. Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Time: ~15,000–5,000 BCE

Region: Western and Central Europe

Key evidence: Mesolithic genomes from La Braña (Spain), Loschbour (Luxembourg) and Scandinavian sites form a tight cluster distinct from both Near Easterners and later farmers (Fu et al., 2016).

These are descendants of Ice Age Europeans who survived in refugia during the Last Glacial Maximum and re-colonised Europe as the ice retreated. They had:

Characteristic allele combinations for dark skin and light (often blue) eyes in some individuals

Distinct cranial morphologies relative to early farmers

High mobility and small group sizes

Modern Europeans don’t have “pure WHG,” but Northern and Western Europeans, especially in the Baltics, Scandinavia, and parts of the British Isles, carry elevated WHG ancestry relative to the European average (Lazaridis et al., 2014).

3. Natufian / Levant–Mesopotamian–Related Ancestry

Time: ~14,000–7,000 BCE (Natufians and Early Levantine farmers)

Region: Levant (Israel, Jordan, Lebanon) and later Mesopotamia

Key evidence: Genomes from Natufian hunter-gatherers and Pre-Pottery Neolithic Levantines form a distinct cluster, with substantial “Basal Eurasian” ancestry and limited WHG-like input (Pankratov et al., 2024).

Europeans don’t usually receive this ancestry directly from Natufians, but indirectly through:

Anatolian Neolithic farmers, whose Near Eastern ancestors had substantial Levant/Iran-related ancestry

Caucasus- and Iran-related components mixed into Steppe populations

This helps explain why Southern Europeans (Greeks, southern Italians, some Iberian regions) sit genetically closer to Near Eastern populations than WHG-rich northern Europeans do.

In my own admixture analysis, I label this component “Levant–Mesopotamia Neolithic”, separate from the “Anatolian Farmer” cluster, because they peak in slightly different ancient cultures and regions.

4. Steppe / Yamnaya Ancestry

Time: ~3,300–2,600 BCE (Yamnaya horizon) and later

Region: Pontic–Caspian Steppe (modern Ukraine/Russia)

Key evidence: Haak et al. (2015) and subsequent work show that Late Neolithic Corded Ware and Bell Beaker groups in Central and Western Europe derive a large share of their ancestry from Yamnaya-like Steppe herders—about 75% in early Corded Ware Germans (Haak et al., 2015).

This Steppe ancestry:

Is linked to the spread of Indo-European languages into much of Europe

Combines Eastern European hunter-gatherer and Caucasus/Iran-related ancestries

Becomes ubiquitous in many regions after ~2,500 BCE

Today, Steppe ancestry is especially high in:

The Baltic states

Poland, Belarus, and parts of Russia

Scandinavia

Much of Britain and Ireland (via Bell Beaker expansion) (Olalde et al., 2018).

The Aryan paradox

There is a striking puzzle that emerges when we compare ancient DNA, modern European biobanks, and pigmentation evolution over the last 10,000 years. I refer to it as the Aryan paradox.

Recent work by Pankratov et al. (2024) shows that deep ancestry components such as WHG, Farmer, and Steppe, are still associated with many complex traits in present-day Europeans, even when comparing siblings. These are robust, genome-wide ancestry signals that correlate with height, pigmentation, bone density, heart rate, immune traits, and more. They demonstrate that Europe’s ancient admixture layers continue to shape trait architecture today.

At the same time, traits like eye, hair, and skin colour have undergone exceptionally rapid evolution during the Holocene. As I showed in two earlier Substack posts on

and

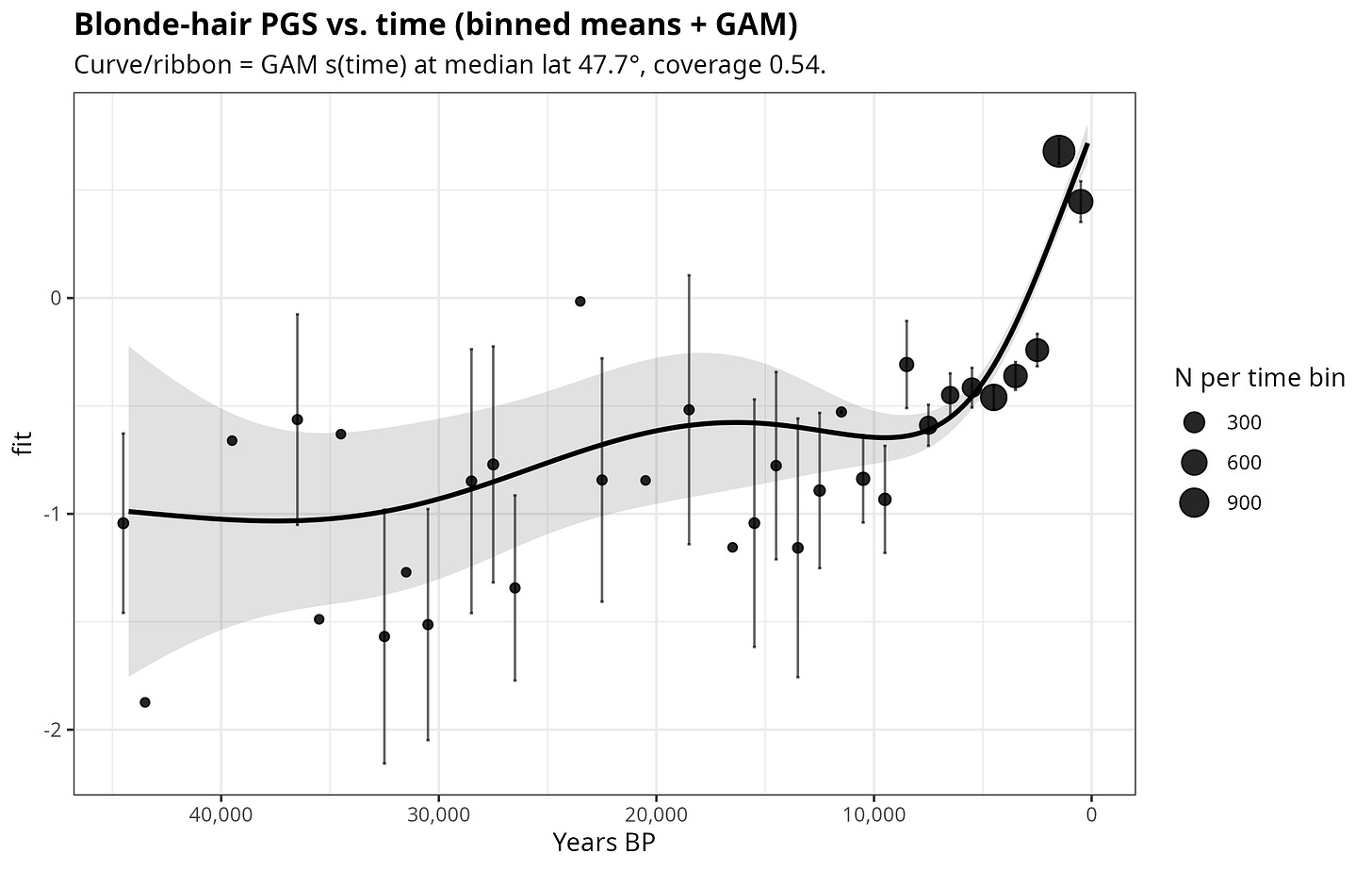

some pigmentation alleles have changed frequency enormously in just a few thousand years. Blue eyes spread among Mesolithic and post-Mesolithic Europeans due to early selection; the key light-skin alleles at SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 rose sharply in the Neolithic and Bronze Age; and hair-colour variants underwent strong recent selection in northern Europe.

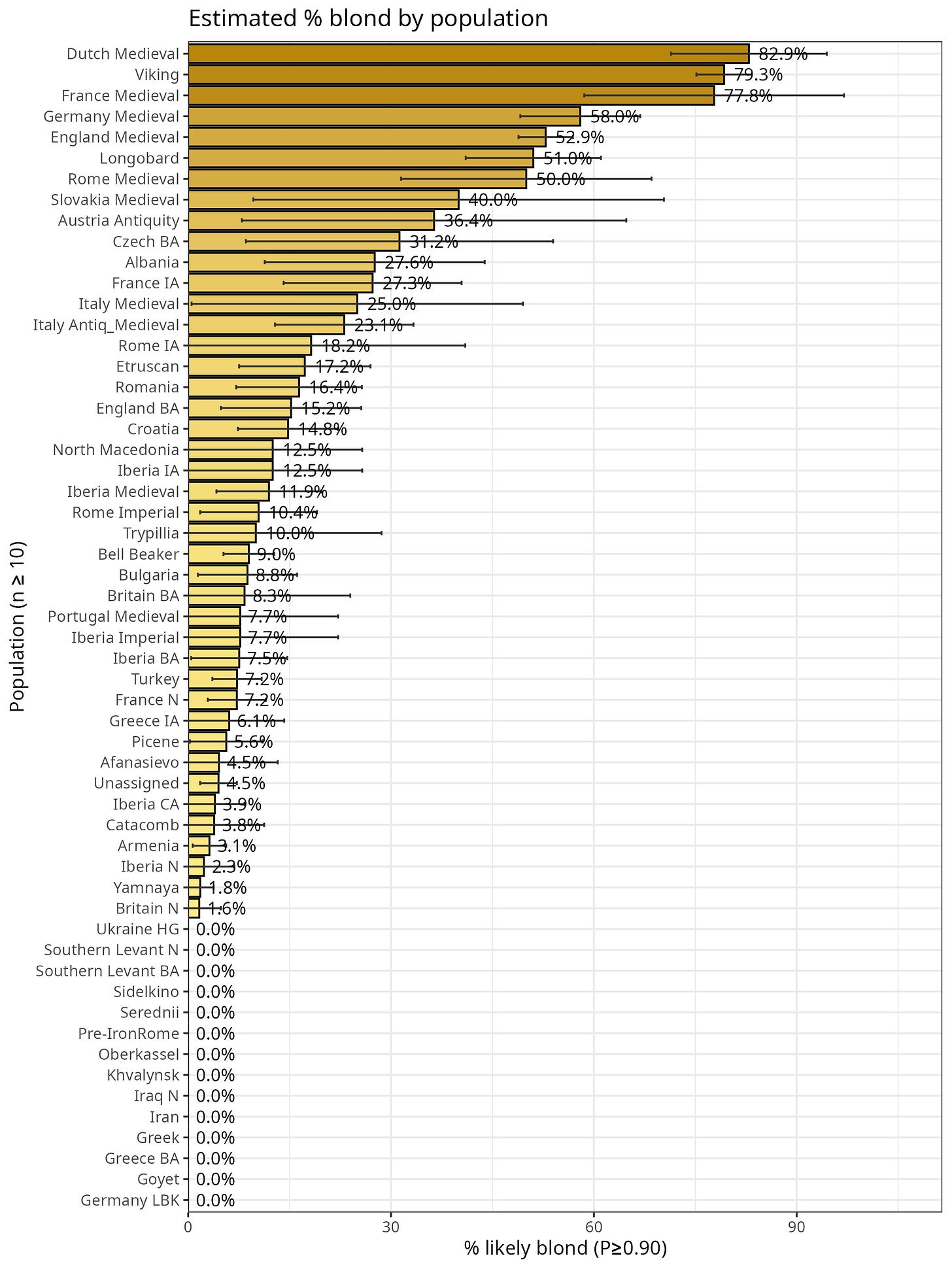

This leads to a paradox. The Yamnaya herders, who contributed so much ancestry to modern northern and eastern Europeans, and who are often imagined as archetypal “Aryans”, were genetically predicted to have mostly dark hair, brown eyes, and moderately pigmented skin. Ancient DNA confirms this: they were not especially blond or pale by modern northern European standards.

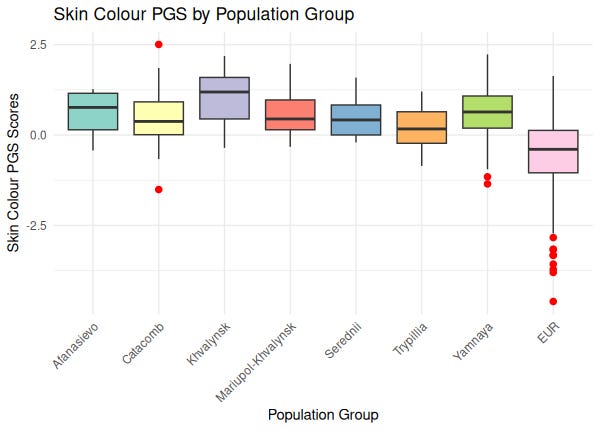

As shown in the plot below (Piffer, 2025), the Yamnaya didn’t have genetically lighter skin than Eastern European hunter-gatherers or farmers, but modern Europeans (EUR) have much ligher skin:

They also had low frequencies of blonde hair:

Consistent with this, Pankratov et al. (2024) show in modern European biobanks that the Steppe-related ancestry was associated with with tall stature , large waist and waist/hip ratio, but also with darker hair and skin pigmentation,

Yet today, the European populations with the highest proportion of Yamnaya ancestry, such as Baltic and some Scandinavian groups, are among the blondest and fairest-skinned in the world.

The resolution is simple but important. Deep ancestry components shape genomes in broad, stable ways, and within modern populations their effects can still be detected (as Pankratov et al. show). But between populations, the relationship between ancestry and appearance can be radically altered by recent, trait-specific selection.

Steppe ancestry itself did not cause extreme blondness or very fair skin. Instead, after the Steppe expansions mixed into Europe, powerful selection on pigmentation genes in northern environments shifted allele frequencies far beyond what the original Yamnaya carried. Thus you can have:

• A deep ancestry component (Steppe) that still influences many complex traits,

yet

• A present-day phenotype (extreme depigmentation) that the original ancestral population did not exhibit.

This is the Aryan paradox: the people with the strongest genetic link to the Steppe herders do not resemble them physically, because key pigmentation traits evolved rapidly after the admixture events, not before them.

For example, the blond hair PGS went up significantly over the last 10K years:

Height as the counterexample

It is worth stressing that height is the major exception to this decoupling between ancestry and phenotype. Unlike pigmentation, where between-group patterns have been reshaped by powerful recent selection, height still tracks Steppe/Yamnaya ancestry both within populations and between populations. This was already hinted at in early ancient-DNA studies, which noted that Bronze Age groups with substantial Steppe ancestry were taller than preceding Neolithic farmers. Modern biobank analyses confirm it: populations with higher Steppe ancestry such as northern and northeastern Europeans tend to be taller on average, and within countries the Steppe component predicts height even after controlling for geography, socioeconomic structure, and in some cases within-family comparisons. In other words, selection has not scrambled the relationship between Steppe ancestry and stature the way it did for pigmentation. Height remains a trait where the deep ancestral signal survives intact at both levels: within populations and across Europe as a whole.

My Admixture Analysis of ~4,000 Ancient Western Eurasians

To tie the literature together, I performed an admixture-based clustering analysis on ~4,000 ancient Western Eurasian genomes spanning:

Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers

Neolithic and Chalcolithic farmers

Bronze Age Steppe and Beaker-associated groups

Iron Age and Medieval individuals

Using a four-way model, I consistently recovered the same four components:

Levant–Mesopotamia Neolithic

Anatolian Farmer

WHG

Steppe

When I averaged ancestry proportions by archaeological culture, I found this pattern:

Mesolithic Europe: almost pure WHG

Early Neolithic Central Europe: overwhelmingly Anatolian Farmer, with minor WHG

Near Eastern Neolithic and Chalcolithic: Levant–Mesopotamia + related farmer lineages dominate

Early Bronze Age Steppe (Yamnaya and related): high Steppe + Caucasus-/Near Eastern–related ancestry

Corded Ware / Bell Beaker: large Steppe component with varying Farmer/WHG mixes

Iron Age/Medieval: stabilized regional mixtures that foreshadow modern European genetic structure

These ancient patterns are the “roots” of the clines we see in present-day Europeans.

Do These Ancestries Still Matter Today?

Evidence from European Biobanks

A natural question is: do these ancestral components still influence modern traits? Or are they just neutral labels that only matter for geneticists?

A recent paper by Pankratov et al. (2024) directly answers this, using hundreds of thousands of individuals from the UK Biobank and complementary analyses in the Estonian Biobank (Pankratov et al., 2024).

They:

Model each modern individual’s genome as a mixture of WHG, Anatolian Neolithic / Early European Farmer, and Steppe (Yamnaya) ancestry.

Regress dozens of complex traits (27+ in earlier work, extended here) on these ancestry components.

Use siblings to show that the associations are not simply due to environmental confounding: differences in ancestry between siblings correlate with differences in traits.

The main findings were:

Height and pigmentation: not surprisingly, these show strong stratification across ancestries, consistent with prior signals of selection.

Cardiovascular and hematological traits: heart rate, platelet count, monocyte percentages and bone mineral density also vary systematically with ancestral components, suggesting that post-Neolithic selection shaped not just “surface” traits but deeper physiology.

The associations are robust inside countries and across biobanks, implying that this isn’t just geography or socio-economic structure.

My Own Results: Linking Ancient Ancestry to Modern Traits

In the second part of this series, I will present my own analyses linking these four ancestries to modern polygenic traits.

Using:

~4,000 ancient individuals as ancestral references

Polygenic scores and allele-frequency–based predictors for traits such as height, pigmentation, and cognitive/behavioural traits

Ancient cultures grouped by their mean proportions of Levant–Mesopotamia, Anatolian Farmer, WHG, and Steppe ancestry.

I will show:

How polygenic height scores track the rise of Steppe ancestry in Bronze Age populations.

How pigmentation-associated variants shift as Anatolian Farmer and Levantine components spread into WHG-dominated Europe.

How more abstract traits (e.g., educational attainment PGS) align with these same ancestral gradients in later periods.

These analyses, combined with the results of Pankratov et al., suggest a coherent picture:

The four ancestral lineages of Europe are not just historical ghosts. They still influence the trait landscape of modern Europeans in systematic, measurable ways.

Conclusion

Ancient DNA has replaced racial typology with something both more accurate and more interesting:

Europe is not a story of three static “races”; it is a dynamic mixture of at least four deep ancestral populations.

These components still matter: work like Pankratov et al. (2024) shows that they help shape the complex trait landscape in contemporary Europeans, from height and pigmentation to heart rate and bone density.

My own analyses of thousands of ancient genomes show how these ancestries rose and fell through time, and how their genetic legacies line up with modern trait architectures.

References

Fu, Q., Posth, C., Hajdinjak, M., Petr, M., Mallick, S., Fernandes, D., Furtwängler, A., Haak, W., Meyer, M., Mittnik, A., Nickel, B., Peltzer, A., Rohland, N., Slon, V., Talamo, S., Lazaridis, I., Lipson, M., Mathieson, I., Schiffels, S., Skoglund, P., … Reich, D. (2016). The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature, 534(7606), 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17993

Haak, W., Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N. et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207–211 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14317

Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Mittnik, A. et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513, 409–413 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13673

Olalde, I., Brace, S., Allentoft, M. E., Armit, I., Kristiansen, K., Booth, T., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Mittnik, A., Altena, E., Lipson, M., Lazaridis, I., Harper, T. K., Patterson, N., Broomandkhoshbacht, N., Diekmann, Y., Faltyskova, Z., Fernandes, D., Ferry, M., … Reich, D. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature, 555(7695), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25738

Pankratov, V., Mezzavilla, M., Aneli, S. et al. Ancestral genetic components are consistently associated with the complex trait landscape in European biobanks. Eur J Hum Genet 32, 1492–1499 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01678-9

Piffer, D. (2025). Why Were the Yamnaya so Successful? An Evolutionary Polygenic Approach. Mankind Quarterly, 65(4), 510-532

Thanks for the interesting and informative article.

Europe? This sounds like West Eurasia, not Europe. Natufian is a more basal older substrate that comes in by proxy through EEF and Steppe. Not a separate component in Europe.

If you're looking for a potential 4th, a more interesting example would be the ANE/Uralic/Nganasan pulse into northeast Europe that is a significant contributor to Finns and others in that region who are still very much European, but have a distinct signal that pulls them in an orthogonal direction on PCA plots.

This is just off the top of my head so I might be wrong, but I feel like there isn’t good justification for unpacking Natufian in this way by forcing a K=4 cluster analysis... like if we're unpacking, why not unpack Steppe into EHG and CHG, and EHG into WHG and ANE, with ANE also coming in via the earlier mentioned Nganasan/Uralic admixture into Finns, Estonians, etc.

I feel like the main 3 from Lazaridis 2014 are the best, and if we start unpacking we'll end up with 5 to 7, not those 4.