The Ice Age Factor: A New (yet Ancient) Genetic Axis of Personality Across Populations

Some people move through life like a quiet lake: hard to rattle, slow to anger, always smoothing over conflicts. Others are more like a thunderstorm: intense, reactive, loud, drawn to stimulation and drama. Most of us live somewhere in between, but we all recognize the types.

We usually explain this with childhood, culture, maybe a bit of “that’s just how I am.” My new study (Piffer, 2025) adds something disquieting and beautiful on top of that: it suggests there is a genetic personality factor that varies across human populations and has, until now, been invisible.

This factor is not one of the usual Big Five. It’s built from three of them—Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism—and it behaves in a very particular way. Populations who score higher on it have, in genetic terms, more Agreeableness and less Extraversion and Neuroticism. In plain language: more cooperative, less stimulation-seeking, less prone to worry and emotional overreaction. Populations who score lower tend in the opposite direction.

It looks, at first glance, a bit like the so-called General Personality Factor (GFP) that psychologists have argued about for years: some overarching “good personality” dimension (Rogoza et al., 2023). But what I’m describing here is different in three important ways.

First, it draws on only three traits—A, E and N—instead of the full five. Second, Extraversion loads negatively on it: a higher score means lower Extraversion, which is not what many GFP models assume. Third, and crucially, it appears most clearly between populations. This is a factor of ancestries, not (yet) of individuals. We don’t know whether the same structure exists within a single country or ethnic group as a clean, individual-differences dimension.

In other words: this isn’t “GFP but rebranded.” It’s a newly identified genetic factor that emerges when you look across human groups and ask how their A, E, and N polygenic scores move together.

A climate-shaped temperament axis

Once you extract this factor, you can score each population on it. A pattern emerges that is hard to ignore.

Many East Asian and Central/Inner Asian populations sit toward the high end of the factor: genetically more agreeable, less extraverted, and less neurotic on this composite. Most European and South Asian groups cluster in the middle. Several African and some Middle Eastern/North African populations sit nearer the low end.

The differences are small in absolute terms but the pattern is consistent enough that it demands an explanation. The one that best fits the data is not a recent cultural quirk, but something much older and slower: climate and ecology during the Late Pleistocene, especially the long, brutal winters of the Ice Age.

Imagine trying to survive eight months of darkness and cold with a small band of humans. Food is scarce, mistakes are costly, and you cannot simply storm off from the group. In such conditions, temperaments that minimize destructive conflict and emotional chaos have an edge. Being impulsive, thrill-seeking, and chronically anxious is not just bad for your mood; it can be fatal for everyone around you.

Over thousands of generations, even tiny selective advantages for people who are more cooperative, less impulsive, and less prone to emotional meltdowns could accumulate. The factor in this study looks very much like a residue of that process: a climate-shaped temperament axis running through our genomes.

Watching the factor drift through 40,000 years

The fun part of this study is that we aren’t stuck with a single snapshot of modern genomes. With ancient DNA, we can watch this temperament factor move through both time and latitude.

In ancient Western Eurasia, I computed polygenic scores for Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism in thousands of samples, some going back more than 40,000 years. Then I did two things at once:

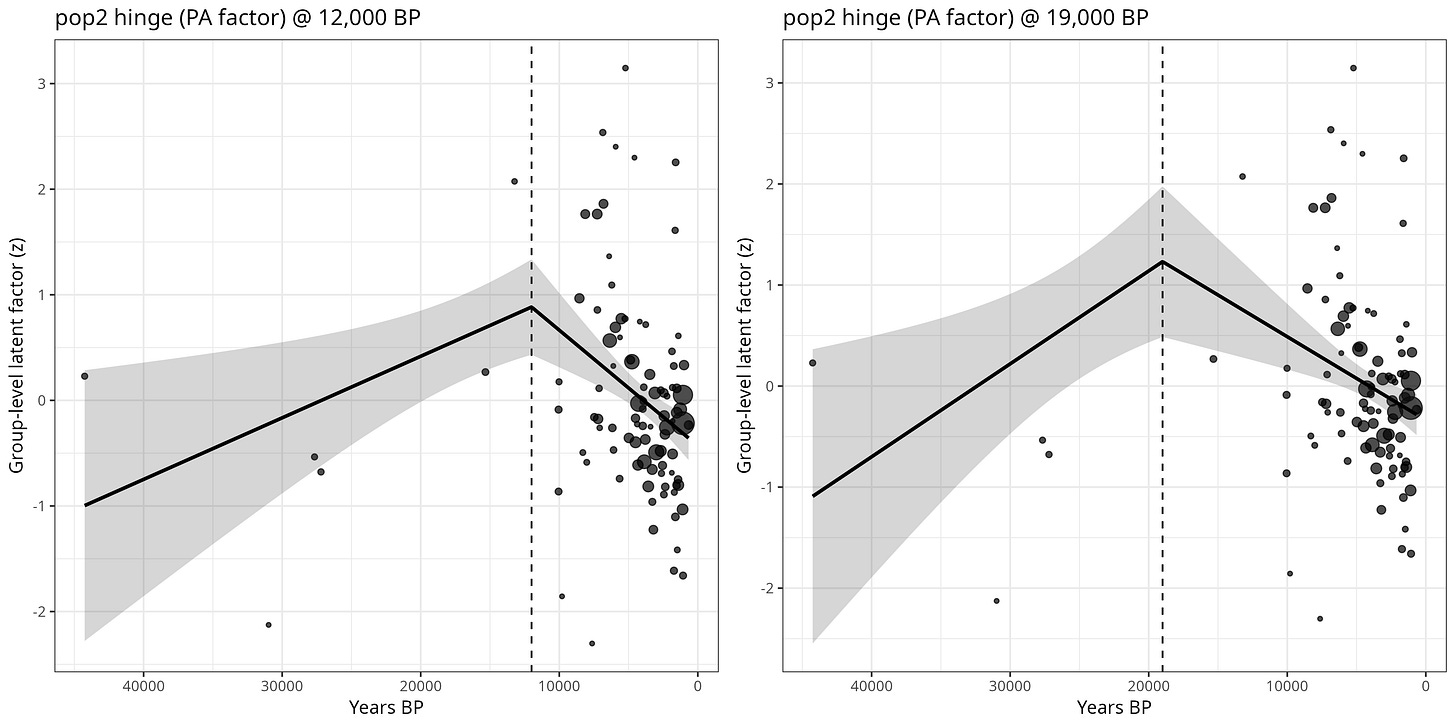

I modeled time with hinge regressions at 19,000 and 12,000 years before present, which correspond to the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the onset of the Holocene.

I included latitude and coverage as covariates, so we can see whether colder, more northerly sites already show a psychological gradient, independent of age.

The trait-level story is very clean. In Western Eurasian ancient DNA, Extraversion and Neuroticism polygenic scores decline as you go north: higher-latitude samples have lower Extraversion and lower Neuroticism, even after adjusting for time and data quality. Agreeableness doesn’t show a strong latitude effect on its own, but Extraversion and Neuroticism do exactly what an Arctic-adaptation story would predict, quietly draining away with every degree of latitude.

When you collapse all three traits into the new A–E–N factor and run the hinge regressions, you get that dramatic biphasic curve: before the Ice Age ends, the factor rises with sample age; after the big climate breakpoints it swings into reverse and starts declining. On top of that temporal pattern, there is a persistent spatial cline: the factor is higher at higher latitudes, roughly +0.06 standard deviations per degree north. Cold, northerly Western Eurasian sites show more of the “calm, cooperative, emotionally stable” profile, warmer and more southerly sites less of it.

So you see two things at once:

over time, the Ice Age ramps this temperament up and the Holocene lets it unwind;

in space, even within the Ice Age, the colder and more northern you go, the stronger the profile becomes.

In Eastern Eurasia, the story bends. The ancient sample is mostly Holocene, so there’s no clean pre-/post-LGM hinge test, and once you control for ancestry components, latitude stops doing much in the ancient East Asian dataset. There is no neat north–south gradient in Extraversion and Neuroticism there, unlike Western Eurasia. Instead, it’s specific ancestries—Northeast Chinese, Tibetan, Jōmon, Siberian, Arctic—that push the agreeableness–emotional-stability composite upward. That suggests that by the time we can observe them, Eastern lineages are already carrying the Ice-Age-shaped profile, and later Holocene dynamics are more about who your ancestors were than exactly how far north you lived.

A factor of populations, not personalities (yet)

At this point it is very tempting to say: “So this is my personal all-in-one personality score.” That would be premature.

The factor I’m talking about is most robustly defined between populations. It’s a way of summarizing how ancestries differ in their genetic loadings on Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism. Whether the same structure exists neatly within a single population, as a meaningful individual-differences dimension, is still an open question. That needs to be tested with careful psychometrics and within-group genetic data.

So when I say East Asians tend, on this factor, to be more genetically tilted toward calmness and cooperativeness than many other groups, I’m describing a small average shift. Within any population, you can find people at every point along the axis, from glacially steady to electrically reactive.

What this work does show, I think, is that our nervous systems are not floating free of evolutionary history. They carry faint, statistical echoes of the climates and ecologies in which our ancestors survived, or failed to.

Test how “hot”/”cold” your personality is

If you’re curious where you land on this axis, I’ve built a short personality test that takes your Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism, collapses them into a single composite, and shows your place on a bar that runs from deep blue to bright red.

The details, and the test itself, are for subscribers.

Members can take the test below.