The Origins and Spread of Blond Hair in Europe: Insights from Ancient DNA

Were Vikings really blond? Were Romans as dark-haired as Hollywood suggests? And where in Europe did blond hair first appear?

In my last post - The Origins and Spread of Blue Eyes in Europe: Evidence from Ancient DNA - I explored how over 4,000 ancient genomes revealed the surprising history of Europe’s most iconic eye color. Vikings, Romans, steppe pastoralists, and Ice Age hunter-gatherers all played their part in the story of how blue eyes spread across the continent.

This time, I turn to another striking trait: blond hair. Just as with eye color, ancient DNA lets us test popular stereotypes such as: “Were Vikings really blond? Were Romans mostly dark-haired?” and trace when and where the first blond individuals appeared in the archaeological record.

But while eye color genetics is relatively simple - largely controlled by a single switch in the HERC2/OCA2 region, together with some fine tuning genetic variants - blond hair is far more complex. It is a highly polygenic trait, influenced by hundreds of variants across the genome. A major GWAS of hair color in the UK Biobank (Morgan et al., 2018, Nature Communications) identified more than 200 genetic signals explaining ~73% of SNP heritability, with no single gene dominating the way MC1R does for red hair.

In other words: there is no single “blonde gene.” Instead, blond hair emerges from the combined action of many small-effect variants. By scoring thousands of ancient genomes on these polygenic signals, I reconstructed how blond hair frequencies shifted across Europe’s deep past.

The Results: Surprising Revelations

I estimate blond hair frequency using a continuous blond-hair polygenic score (PGS) and a transparent probabilistic classifier, rather than the proprietary HIrisPlex-S system. Specifically, I fit a two-component Gaussian mixture to individual PGS values - one “darker-haired” mode and a “blond-like” tail - and assign each person a posterior probability of belonging to the blond-like cluster. Individuals with ≥90% posterior probability are called “likely blond,” and population-level % blond is simply the share above that cutoff. This approach is reproducible, avoids black-box models, and respects the polygenic nature of the trait.

Population means

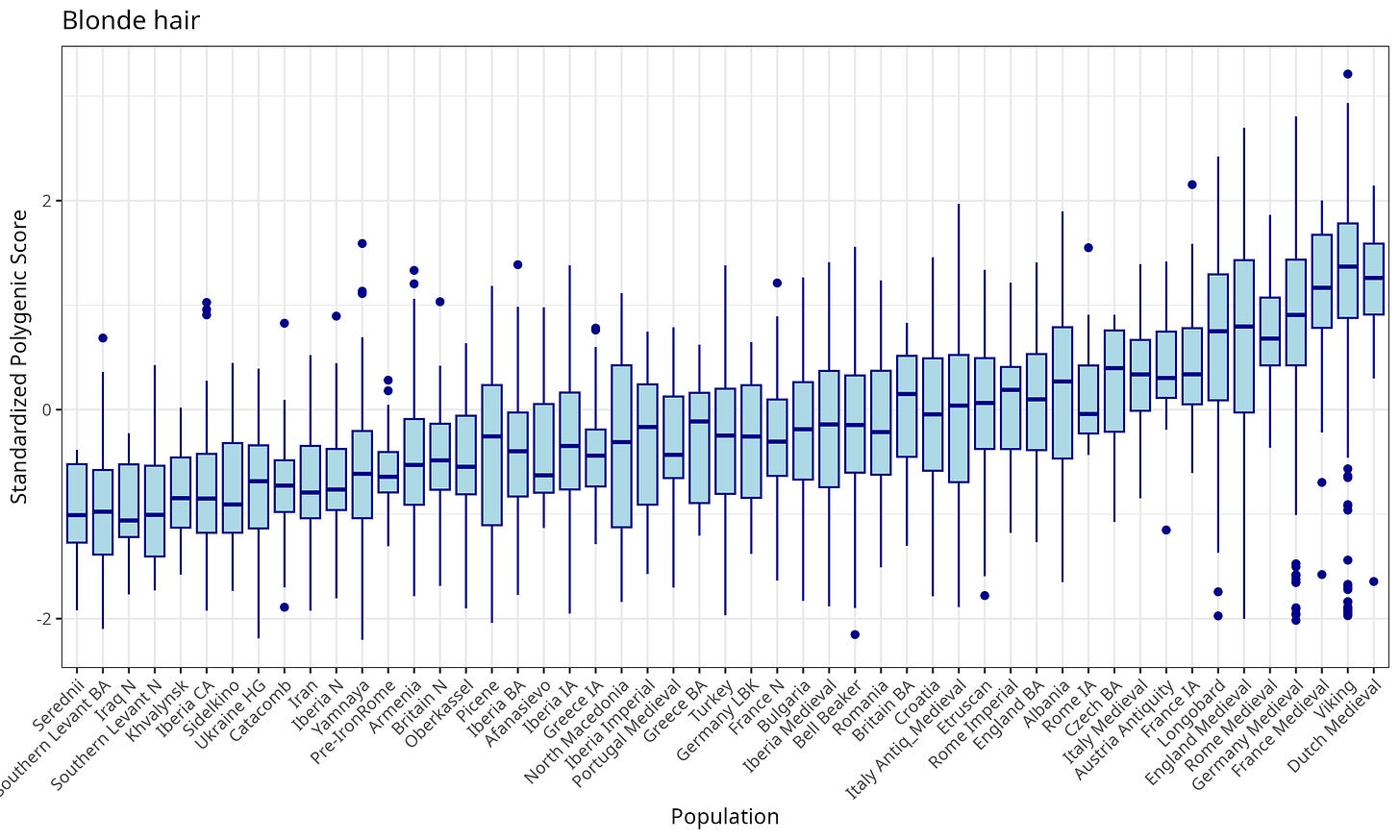

Before turning PGS into “likely blond” calls, it helps to see how the blond-hair polygenic score is distributed within each population. Figure 1 shows standardized scores (z) as boxplots for all groups with n ≥ 10, ordered from darker-leaning to blond-leaning. This reveals which populations are shifted toward higher blond scores (right side) and which cluster below zero (left side), setting up the mixture-model calling that follows.

To complement the individual-level boxplots, I summarize each population by its mean standardized blond-hair PGS. Higher means indicate a right-shifted distribution (more blond-leaning genotypes); lower means indicate a left-shift (darker-leaning).

Figure 1. Blond hair polygenic score

Who clusters on the blond side?

The clearest blond-leaning groups are the Dutch Medieval and Vikings, followed by Medieval France, Medieval Germany, and Medieval Rome. Medieval England and the Longobards also sit well above average, with Iron Age France, Antiquity Austria, and Medieval Italy rounding out the lighter end.

In the middle or mixed:

Bell Beaker communities land just below the overall average—matching their modest blond rate (~9%). Iron Age Rome is slightly above average, whereas Imperial Rome sits almost exactly at the midpoint, reflecting the cosmopolitan mixture that diluted lighter-hair signals.

Who clusters on the dark side?

At the opposite extreme are Serednii, the Southern Levant (Neolithic/Bronze Age), and Iraq Neolithic, along with Khvalynsk, Iberia Chalcolithic, Sidelkino, Ukraine hunter-gatherers, Catacomb, and Iran—all strongly dark-leaning in the PGS.

What about the steppe and Iberia?

Classic Steppe/Eneolithic groups - Yamnaya, Afanasievo, Khvalynsk - sit on the dark side of the distribution, reinforcing that the steppe itself was neither blond nor blue eyed (as demonstrated in the previous post). Iberia trends negative across time: from Neolithic through Bronze/Iron Age and still below average in the medieval period, consistent with the low blond calls seen in the barplot.

Keep reading for: Are blue eyes and blond hair tightly coupled across cultures and time? How blond were the Vikings really? Why does Imperial Rome look so different? And which ancestries (Western Hunter-Gatherers, Neolithic Farmers, Steppe/Yamnaya)push the blond PGS up or down?