The Right-Wing Immigration Paradox

How Meloni’s Italy shows that immigration isn’t necessarily a Left–Right divide — only a difference in motives.

We’re used to thinking of immigration as a partisan issue:

The Left welcomes it; the Right resists it.

But in Italy today, that distinction has collapsed.

Giorgia Meloni’s government, the self-proclaimed defender of national borders, is presiding over one of the largest expansions of migrant labour inflows in Italian history.

Despite all the rhetoric about “stopping the boats,” neither irregular nor regular immigration has decreased. The slogans may be nationalist, but the policies are deeply neoliberal.

1. The myth of the “anti-immigration” Right

When Meloni took power in 2022, she promised to end “mass illegal immigration.”

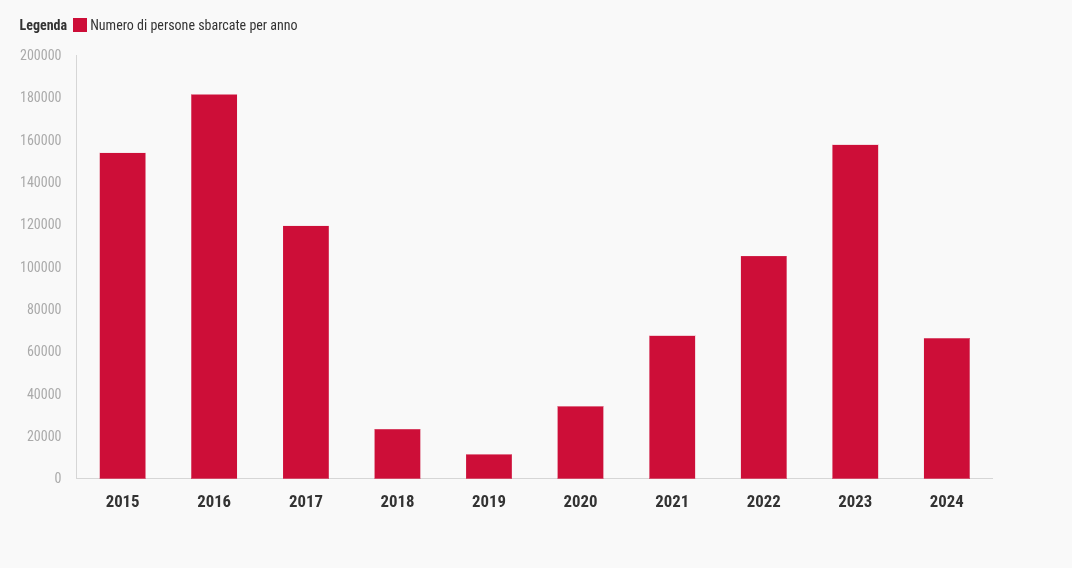

In practice, irregular arrivals by sea have remained high. 2023 saw over 150,000 arrivals — the highest number since 2016 — and although 2024 brought a partial slowdown, there was no return to the low levels of the Salvini era (2018-2019).

That matters because it shows what a truly hardline interior policy did look like.

Under Matteo Salvini, Interior Minister and vice premier in 2018–2019, irregular sea arrivals fell to historic lows — around 23,000 in 2018 and 11,500 in 2019 — through an aggressive campaign of port closures, NGO criminalisation, and cooperation with Libyan authorities.

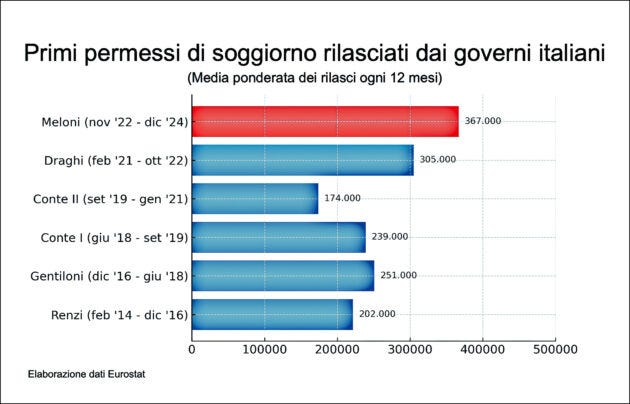

This chart shows the number of residence permits by government:

Whatever one thinks of the methods, the numbers prove a simple point:

A right-wing government can reduce irregular immigration — if it truly wants to.

Meloni, by contrast, has largely normalised irregular inflows while expanding legal channels on a massive scale.

2. From 69,700 to 497,550: the quiet explosion of legal migration

To grasp the scale of this shift, compare the Decreto Flussi before Meloni’s tenure with the one she just approved.

Pre-Meloni (DPCM 21 December 2021, published 17 January 2022):

Total quota: 69,700 workers.

Seasonal work: 42,000 places.

Non-seasonal & self-employed: 27,000 places, of which 20,000 were for subordinate work in transport, construction, and tourism-hospitality — limited to citizens of countries with bilateral migration agreements.

Now fast-forward to Meloni’s Decreto Flussi 2026–2028, approved June 2025:

Total authorised entries: 497,550 over three years.

Annual quotas: 164,850 (2026), 165,850 (2027), 166,850 (2028).

Breakdown: 267,000 seasonal workers (mostly agriculture/tourism) + 230,550 non-seasonal and self-employed.

That’s a seven-fold increase compared to the last pre-Meloni plan.

And this under a government that campaigned against “mass immigration.”

The Ministry of Labour justified it as necessary to meet “manpower indispensable to the national economic and productive system and otherwise not available.”

Translation: our economic model requires a steady flow of foreign labour to keep costs low.

3. A government of “closed ports” that keeps the gates wide open

This is the central contradiction of Meloni’s Italy:

Symbolically, the government waves the flag of border sovereignty.

Materially, it organises one of Europe’s largest inflows of migrant workers.

The “illegal migrant” at sea is condemned; the bracciante in the tomato fields is celebrated — especially when photographed for the Ministry of the Interior’s website.

The message is clear: migration is acceptable when it serves employers.

5. The real reason for the “quiet embrace” of foreign labour

Government press releases talk about demographic decline and labour shortages.

But the real driver is political economy.

Meloni’s social base includes farmers, industrialists, and small-business owners — constituencies built on cheap, disposable labour. Italians understandably walk away from jobs when pay and conditions are substandard; rather than raising wages and protections, employers press for a steady inflow of workers with weaker bargaining power.

Agricultural labourers in southern Italy — many of them African or South Asian migrants — still toil under the caporalato system: unregulated gangmasters, sub-minimum wages, 10-hour days in extreme heat, and makeshift housing.

These are the conditions that make Italian produce competitive — and that domestic workers naturally reject.

Brain drain & high-skill talent: what Meloni did (and didn’t)

Italy’s “brain drain” isn’t new, and Meloni didn’t invent the only generous tool that actually targets researchers: the 2010 tax break that lets professors and researchers exclude most of their income if they move back to Italy. It survives, but it’s niche — a band-aid, not a strategy.

What did change under Meloni is the broader impatriati regime (for non-academics): from 2024 it became less generous and more restrictive, a clear signal that high-earning returnees aren’t the priority.

And for foreign highly skilled talent? Italy leans on the revamped EU Blue Card (outside Flussi quotas), but bureaucracy and credential recognition still choke volumes. There’s no US-style fast track with scale and clear permanent-residence pathways.

Bottom line: the government’s migration machine is built around low-/mid-wage inflows to satisfy employers — not around competing globally for scientists, engineers, or PIs. Even on talent, the policy logic mirrors the rest of the post: cheap labour over brains.

Low wages as policy: why Italy needs cheap labour

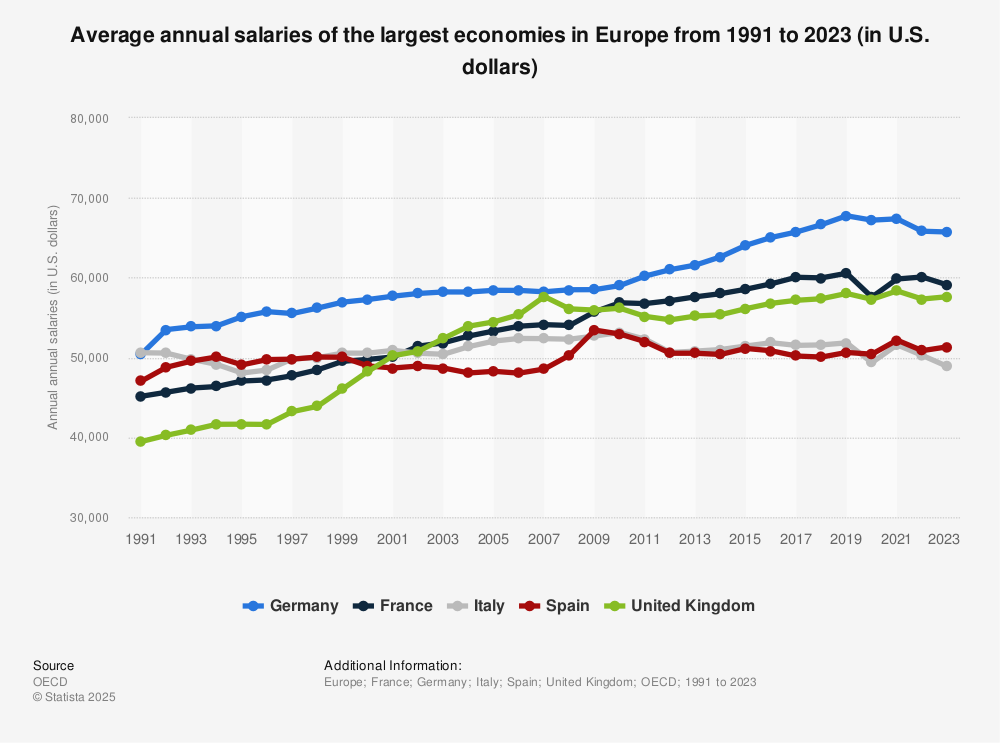

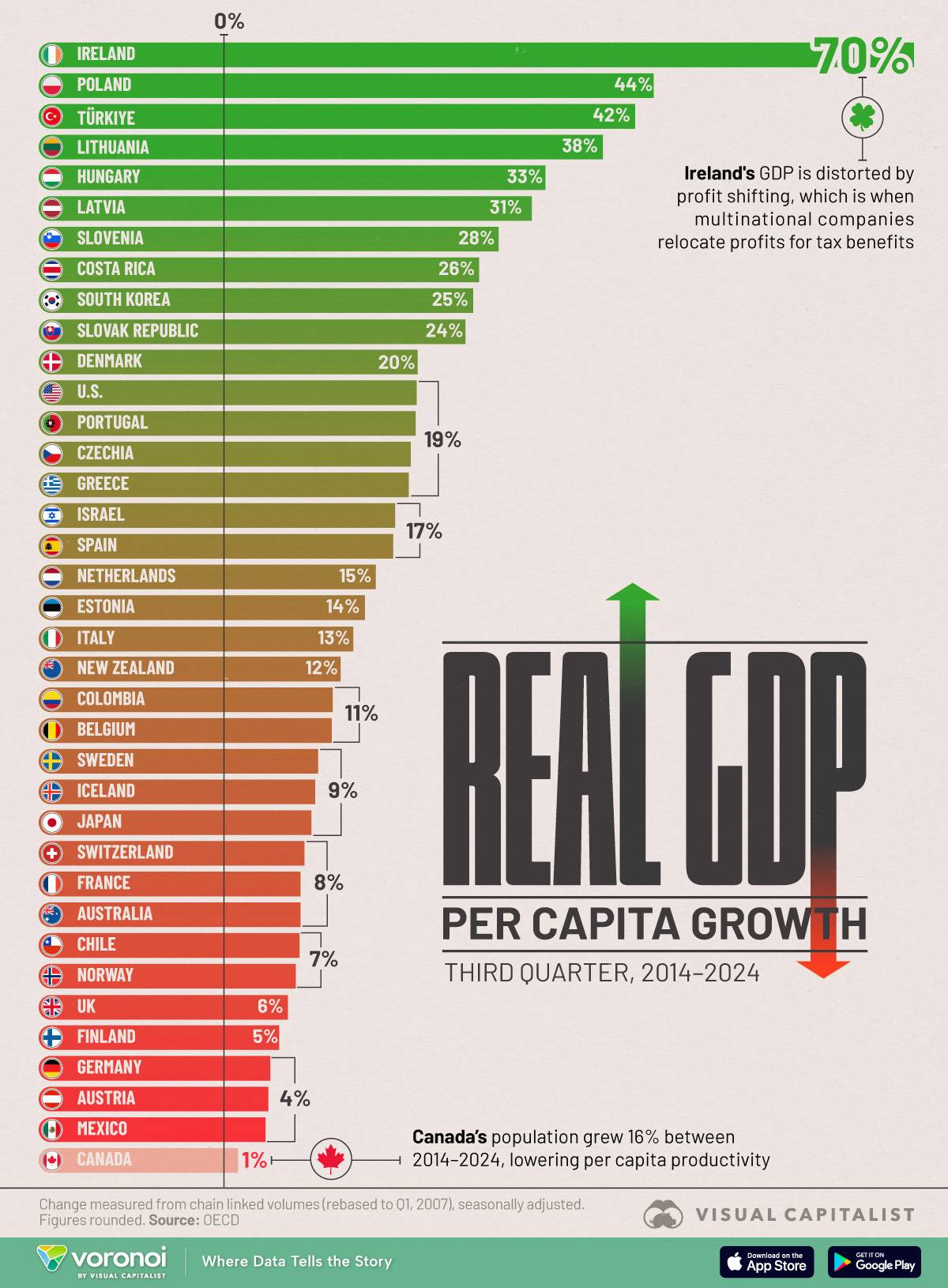

Salaries have stalled compared to other EU countries:

This is in contrast to per capita GDP, which has increased more than in Germany or France:

Italy’s economy has leaned on low wages for years. While GDP per capita has increased, salaries have lagged most EU peers.

Wage suppression ≠ lack of growth: Firms captured the gains; workers didn’t. That’s why employers lobby for migrant inflows that hold pay down rather than investing to make these jobs decent.

Dual labour market: a core of protected insiders vs. a growing periphery of temporary/seasonal, low-paid, outsourced workers (many of them migrants).

Small-firm equilibrium: fragmentation, weak capital investment, and low productivity upgrades mean the path of least resistance is cheap labour over technology.

Political alignment: the Decreto Flussi scales up exactly the kind of labour the system runs on—seasonal, replaceable, price-sensitive—locking the country deeper into a low-wage competitiveness trap.

Bottom line: Italy doesn’t just “have” low wages; it chooses them.

6. The neoliberal heart of “sovereigntist” politics

What Meloni has built is a two-tier migration regime:

Irregular migration demonised for populist theatre.

Regular migration expanded for business convenience.

It’s immigration without ideology — a functional machine for maintaining low wages in key sectors (agriculture, tourism, care work, logistics).