The Rise of Rome and the Rise of Polygenic Scores

Why did Rome, rather than any of its many rivals in Iron Age Italy, become the core of an empire?

A muddy settlement on the Tiber turns into a machine that can raise armies, write laws that outlive empires, build roads that stitch a continent together, and carry water for millions through aqueducts, while running a Mediterranean-wide bureaucracy for centuries. The usual explanations are familiar: institutions, military discipline, geography, luck. All true, and none of them feels fully satisfying on its own. Many societies possessed some of these advantages. Rome was unusual in how consistently it turned them into scalable institutions.

There is another angle that is rarely discussed, mostly because until recently it was not testable. What if part of Rome’s advantage was carried in its people, as average differences in traits linked to learning, planning, and administration?

Ancient DNA makes it possible to ask that question directly. Using the AADR dataset and educational attainment polygenic scores, Iron Age and Republican-era Romans come out unusually high. Besides exceeding earlier Italian groups, they sit at the top of the entire ancient European distribution, even after accounting for sample age and genomic coverage.

That by itself does not explain the rise of Rome. But it does suggest a sharper hypothesis: Rome’s institutions may have been built and operated by a population that, on average, was unusually well suited to master and scale complex social systems.

Why bring genetics into this at all?

A useful precedent for thinking this way comes from economic history. One influential argument is that England’s escape into sustained modern growth may have been helped not only by markets and institutions, but also by slow-moving demographic change. Over many centuries, higher-status groups in preindustrial England often had more surviving children, and their descendants gradually spread through the wider population. If the traits associated with economic success were partly heritable, this process could slowly shift the population distribution of characteristics linked to human capital and competence, making complex economic systems easier to sustain at scale. This is the core mechanism proposed by Gregory Clark in A Farewell to Alms.

This is not a genetic determinist claim. Institutions are a major factor. The point is that institutions are operated by people, and the returns to good rules depend in part on the distribution of skills and dispositions in the population. Even modest shifts in population-level human capital could change how effectively institutions function, how quickly they scale, and how resilient they are under stress.

My recent work with Prof. Connor - which I summarized in a previous post - tries to bring this hypothesis into the molecular era by asking a direct question: do ancient populations differ in polygenic signals for educational attainment in a way that tracks historical differences in complexity and state capacity?

In earlier work, we reported that Republican Romans had higher cognitive polygenic scores than both pre-Roman Italians and later Imperial-period Romans. Here I place Roman samples into a wider European reference frame using AADR, rather than comparing them only within Italy and across a few periods.

The “Republican Rome” label here refers to the AADR group Italy_IA_Republic (ca. 2830–2250 years BP, roughly ~880–300 BCE), which spans the late Iron Age through the early and middle Republic; for the purposes of this analysis, it is best understood as a continuous central Italian Iron Age population rather than a sharp archaeological break between “Regal/Kingdom” and “Republican” phases.

The data

This post uses AADR v62, a large public compilation of ancient human genomes with archaeological labels (site, culture, and date). Each individual has genotype data on the standard 1240k capture panel, which targets about 1.24 million SNPs widely used in ancient DNA.

The outcome I analyze is an EA polygenic score. Here EA stands for educational attainment, a GWAS-based phenotype that broadly captures genetic influences on years of schooling and closely related cognitive and behavioral traits. A polygenic score (PGS) is a single number computed by summing many genetic variants across the genome, each weighted by its GWAS effect size. It is not a measure of an individual’s achieved education in the past. It is a genetic predictor derived from present-day samples.

To reduce dependence on any single GWAS, I compute two educational attainment polygenic scores using genome-wide significant SNPs (p < 5 × 10⁻⁸) from two large studies: Lee et al. (2018), which I refer to as EA3, and Okbay et al. (2022), which I refer to as EA4. I then average EA3 and EA4 within each individual to obtain a single combined EA score per person, and Z-standardize this combined score across individuals so results are reported in standard deviation units and are comparable across analyses.

Ancient DNA varies in data quality, so I also compute coverage as the fraction of the 1.24 million 1240k target SNPs that are actually observed in each sample. This matters because missingness can distort polygenic scores if it differs systematically across groups or time periods.

Finally, I run the analyses at two levels:

Individual level: each person is one data point

Group level: each population label is summarized by its mean values

Throughout, I control for two core confounders whenever appropriate: sample age (Years BP) and coverage. I also restrict comparisons to groups with at least 10 individuals to avoid unstable means driven by tiny samples.

A baseline pattern in Europe: later samples score higher

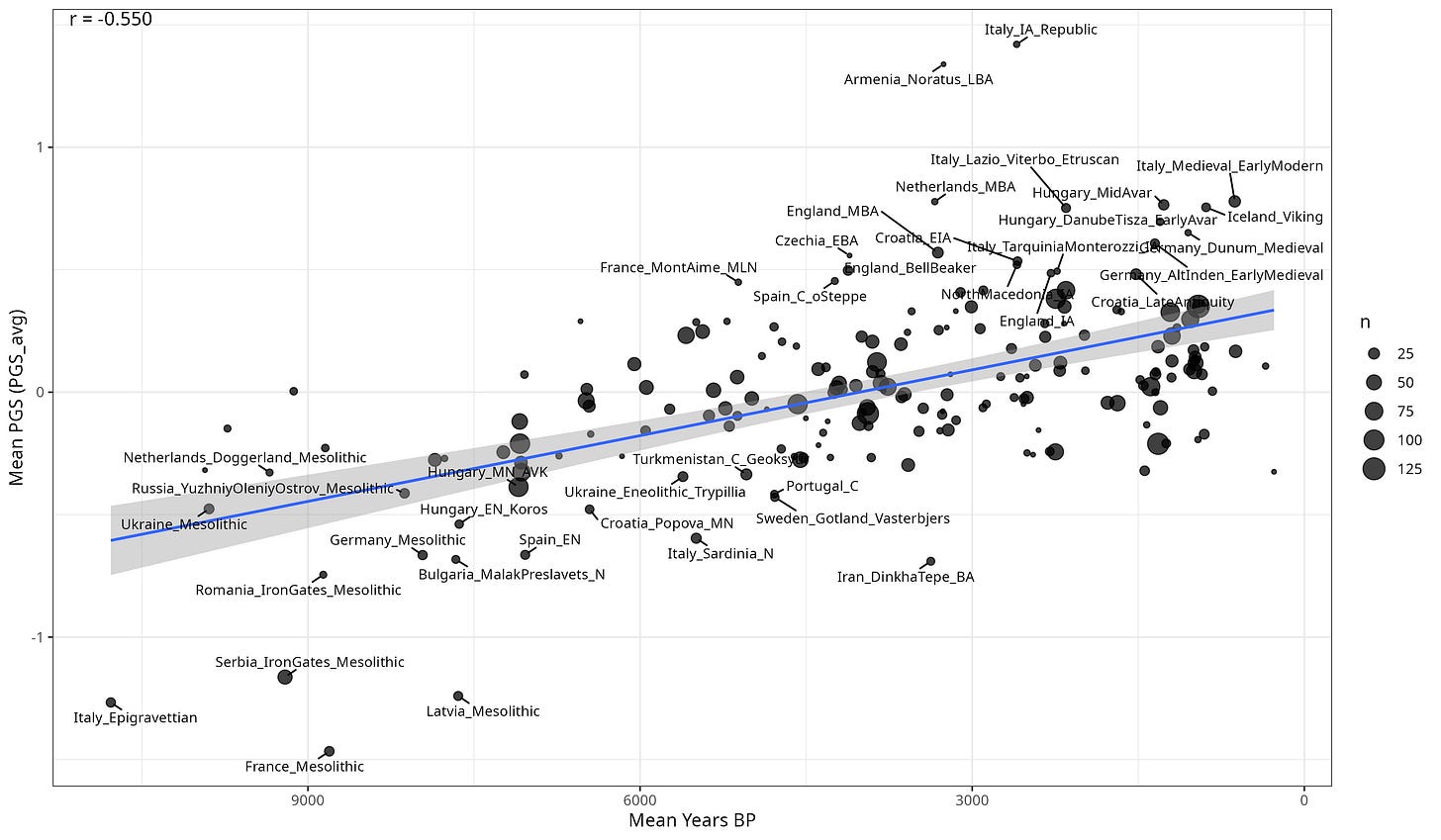

Before focusing on Rome, it is necessary to establish the background trend. Across ancient European populations, educational attainment polygenic scores increase toward the present. At the group level, the correlation between mean Years BP and mean Educational Attainment (EA) polygenic score is about −0.55. Older groups tend to score lower, and more recent groups tend to score higher.

Figure 1 shows this pattern using population means. Years BP is plotted on the x-axis and reversed, so the present lies on the left and the deep past on the right. The slope is clearly negative, indicating a long-term increase in EA polygenic scores across Europe.

Figure 1. Educational polygenic scores rise toward the present across ancient Europe

Italy_IA_Republic lies well above the regression line, indicating a large positive residual relative to the Europe-wide age trend.

This background trend is important, because it sets the baseline expectation for any late population. The real question is whether Rome is simply late, or unusually high even for its time.