The Unabomber’s Blind Spot: Why Humans Evolved Past His Theories (But His AI Warnings Still Matter): Insights from ancient DNA

A brief autobiographical note

Introduction

I first encountered Industrial Society and Its Future in a period of quiet dissatisfaction with modern life—a feeling I had long tried to rationalize away. Reading Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto, I felt something profound stir: not agreement with his methods, but recognition in his diagnosis. His critique of modernity—the idea that we are Stone Age minds suffocating in an artificial, technological world—resonated deeply. It echoed a feeling I had carried since adolescence: that something essential had been lost in our headlong rush toward progress.

That reading reawakened a dream I had shelved years earlier, when I was still a teen —to live closer to nature, to seek out simplicity not as an aesthetic, but as a way of life. Within a year, I had bought a small hut in the mountains and began spending more and more time there. Kaczynski's words didn’t create that longing, but they gave it structure, urgency, and a kind of philosophical clarity—a clarity that was deepened by my own lived experience: the quiet rhythm of seasons, the self-sufficiency of splitting wood for winter, the way the isolation sharpened my senses and dissolved the noise of modern life. Yet, as time passed and I delved deeper into evolutionary psychology and new genetic research, I began to question the very premise that had once felt so undeniable.

Kaczynski’s assumption that we are psychologically frozen in the Stone Age—hopelessly mismatched to modern life—turns out to be only part of the story. New findings from ancient DNA and polygenic scoring suggest that humans have been rapidly adapting to civilization, in both body and mind.

This essay is my attempt to reconcile those two truths: the visceral resonance of Kaczynski’s critique, and the scientific evidence that complicates it. It’s also a reflection on why the dream of “going back” is not just impractical—it may no longer even be desirable.

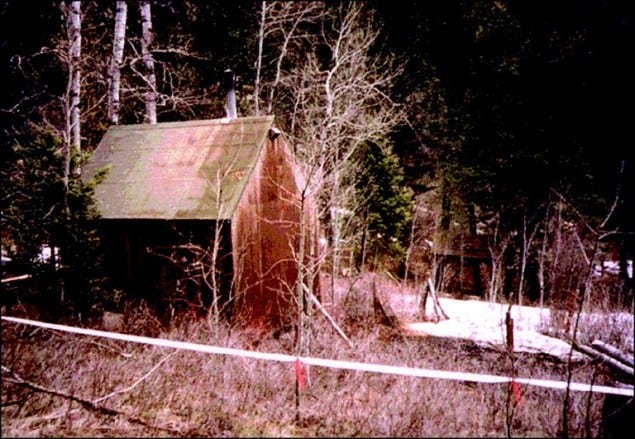

Ted Kaczysnki’s cabin in Lincoln, Montana

Kaczynski’s Core Thesis: Evolutionary Mismatch

In paragraph 33 of his manifesto, Kaczynski lays out what he calls the “power process.” Humans, he writes, need goals, effort, and achievement in order to feel psychologically healthy. Modern society short-circuits this process, offering artificial goals and meaningless work while stripping people of autonomy.

This premise aligns with what evolutionary psychologists call the mismatch hypothesis—the idea that our minds evolved in hunter-gatherer settings and are ill-suited for modern, industrial life. Kaczynski takes this further: not only are we mismatched, he argues, but technological society is so fundamentally incompatible with our nature that it must be destroyed.

However, Kaczynski never clearly articulates what “going back” means. Is he proposing a return to pre-industrial village life? Agrarian society? Hunter-gatherer bands?

The Genetic Counterargument: Humans Have Evolved With Civilization

The Polygenic Revolution

Recent breakthroughs in ancient DNA and polygenic scoring—particularly studies published in 2024 and 2025 (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024; Piffer, 2025; Akbari et al., 2024) tracing European and Asian genomes from the Paleolithic through the modern era—show that humans have not stood still since the Stone Age.

Declining Mental Illness Risk: Polygenic scores for traits like schizophrenia, neuroticism, and depression have declined over time, suggesting selection against psychological vulnerability in increasingly complex societies.

Rising Cognitive Capacity: At the same time, scores associated with intelligence, educational attainment, and autism spectrum traits have increased. Human populations appear to have been selected for traits advantageous in cognitively demanding environments.

Focus and Information Filtering: Schizophrenia, notably, involves difficulty filtering stimuli. As its prevalence declined genetically, humans may have become better adapted to function in dense, information-rich modern settings.

This genetic evidence directly challenges Kaczynski’s static model of human nature. We are not Stone Age brains projected into the future—we are the products of millennia of biocultural co-evolution.

What Kaczynski Got Right: The Acceleration Problem and the Rise of AI

While Kaczynski’s view of human nature was overly static, he correctly identified a critical temporal mismatch: the pace of technological change is far outstripping our ability to adapt to it, whether biologically, socially, or psychologically.

The Compression of Adaptive Timeframes

Agriculture: ~10,000 years of co-evolution

Industrial society: ~250 years of adaptation

Digital age: ~30 years of adjustment

AI revolution: Unfolding in real time

Even if we’ve been evolving with civilization, the acceleration curve is undeniable. Evolution by natural selection—especially for complex behavioral traits—cannot keep up with exponential shifts in our cognitive environment.

This is where Kaczynski’s critique regains surprising power. He saw clearly that acceleration itself, not just industrialism, was destabilizing—and that each wave of innovation would create more disruption than the last.

Kaczynski’s Warnings About AI and Automation

One of the most striking examples of his foresight is his discussion of artificial intelligence and automation. Writing in the mid-1990s—before machine learning, GPTs, or widespread internet usage—he predicted that humans would become increasingly controlled by intelligent systems, even as we imagined ourselves in charge.

Neither scenario, he argued, would preserve genuine human freedom. If the machines make the decisions, humans become irrelevant. If humans remain in control, that control will rest with an elite few.

On the Rise of AI and Intelligent Machines

Kaczynski anticipated the potential rise of artificial intelligence, though he left some room for uncertainty. As he wrote, “But suppose now that the computer scientists do not succeed in developing artificial intelligence, so that human work remains necessary.” This cautious phrasing shows that while he considered AI a likely outcome, he did not assume its inevitability.