There Was Never a Sapient Paradox

A critique of the standard model of behavioral modernity and the assumptions behind it.

TL;DR

The standard story in anthropology says that anatomically modern humans appeared early, around 200 thousand years ago, but behaved like modern humans only much later. This is called the “sapient paradox”. The new study by Jakobsson et al. (2025) gives important new genomes from ancient southern Africans, but it still relies on the same binary idea: same anatomy means same cognitive potential. Culture is supposed to explain everything.

This article argues that the paradox is artificial. Behavior is a spectrum, not a switch. Cognition evolves, genes evolve, polygenic scores shift, and different human populations did not necessarily have the same cognitive potential. The Jakobsson et al. paper accidentally exposes its own assumption: that all present day populations are cognitively identical. Once this assumption is questioned, the paradox disappears.

Key genetic terms

Fixed.

A genetic variant is fixed in a population when every individual carries the same version of the allele. Frequency is 100 percent. There is no variation at that position in the population.

Polymorphic.

A variant is polymorphic when two or more alleles are present in the population. The frequency might be 20 percent, 50 percent, or 70 percent, but not 100 percent.

The paradox that is not

A new Nature paper by Jakobsson et al. (2025) presents high coverage genomes from ancient southern Africans dated between 10,000 and 150 years ago. These genomes show remarkably deep variation within Homo sapiens, including many amino acid changing variants that global datasets had missed. Importantly, some variants previously claimed to be fixed in all modern humans are actually polymorphic in ancient and present day Khoe San. This includes the TKTL1 variant that had been proposed to increase neocortical neurogenesis and contribute to modern human cognitive abilities. Jakobsson et al. show that the supposedly human specific allele is far from fixed in southern African populations.

This weakens any simple model where a single coding mutation created recognisably modern cognition. But the paper remains tied to the traditional framework of the sapient paradox, which claims that there is a mysterious gap between anatomical modernity and behavioral modernity.

They write:

“As behavioural and cognitive traits are largely heritable, southern Africa’s deep Homo sapiens genomic record could aid in disentangling the ‘sapient paradox’, whereby anatomical modernity purportedly predates modern behaviour. However, this may not be straightforward, because some genes governing cognition and anatomy evolved rapidly in the early human lineage, and genetic variants governing rapid neuron developments thought to be fixed in humans are highly variable in some populations .”

According to that model, early Homo sapiens already looked like us but did not behave like us, and the late arrival of symbolic and technological complexity is treated as a puzzle that needs a special explanation.

The paradox exists only because behavior is treated as a binary category.

Behavior is not a switch. It is a spectrum. Some behaviors require minimal cognitive complexity. Others require more. Striking flakes is simpler than making composite tools. Composite tools are simpler than long distance networks. Networks are simpler than symbolic notation systems. Human behavioral evolution progressed across many small steps that did not appear simultaneously in every population.

Genetics reinforces this spectrum view. Large GWAS studies show that traits related to cognition, such as intelligence and educational attainment, are highly polygenic and influenced by thousands of variants with tiny effects (Lee et al. 2018; Savage et al. 2018; Davies et al. 2018). There is no sharp genetic boundary that marks a cognitive revolution.

Ancient DNA adds even more support. Multiple time series show directional selection on cognitive related polygenic scores over the Holocene.

These results indicate that average cognitive potential was not constant across Homo sapiens. Instead, it likely shifted gradually in response to demographic and environmental pressures. Early populations may have had lower average polygenic scores for cognition than some later populations. There is nothing paradoxical about this.

Culture amplifies these differences further. Early forager groups were small, fragmented and vulnerable to cultural loss. Large, interconnected populations generate more cumulative culture. The archaeological record therefore reflects both cognitive potential and cultural scaffolding. Early Homo sapiens may not have had either the same cognitive architecture or the same cultural environment as later populations.

The Jakobsson et al. genomes fit perfectly within this polygenic and cultural model. They show that Homo sapiens retained large reservoirs of functional variation. They reveal that variants once thought to be universal are actually polymorphic. And they expose an assumption that quietly structures the traditional interpretation of the sapient paradox.

The Hidden Assumption: All Human Populations Have the Same Cognitive Potential

One passage in Jakobsson et al. makes the assumption explicit. Discussing TKTL1, they write:

“The derived variant has been reported to be almost fixed (99.97 percent) in modern humans in contrast to Neandertals and Denisovans who carry the ancestral variant, but the ancestral variant is common among modern day Khoe San (32 percent), and among the 7 ancient southern African complete genomes (27 percent). Thus, superficially, the derived variant of TKTL1 appears to be almost fixed in modern humans. Yet, its ancestral variant is common in some populations that are under represented in genomic investigations. The derived variant therefore represents a false positive that is unlikely to be important for the development of complex modern human neurological characteristics.”

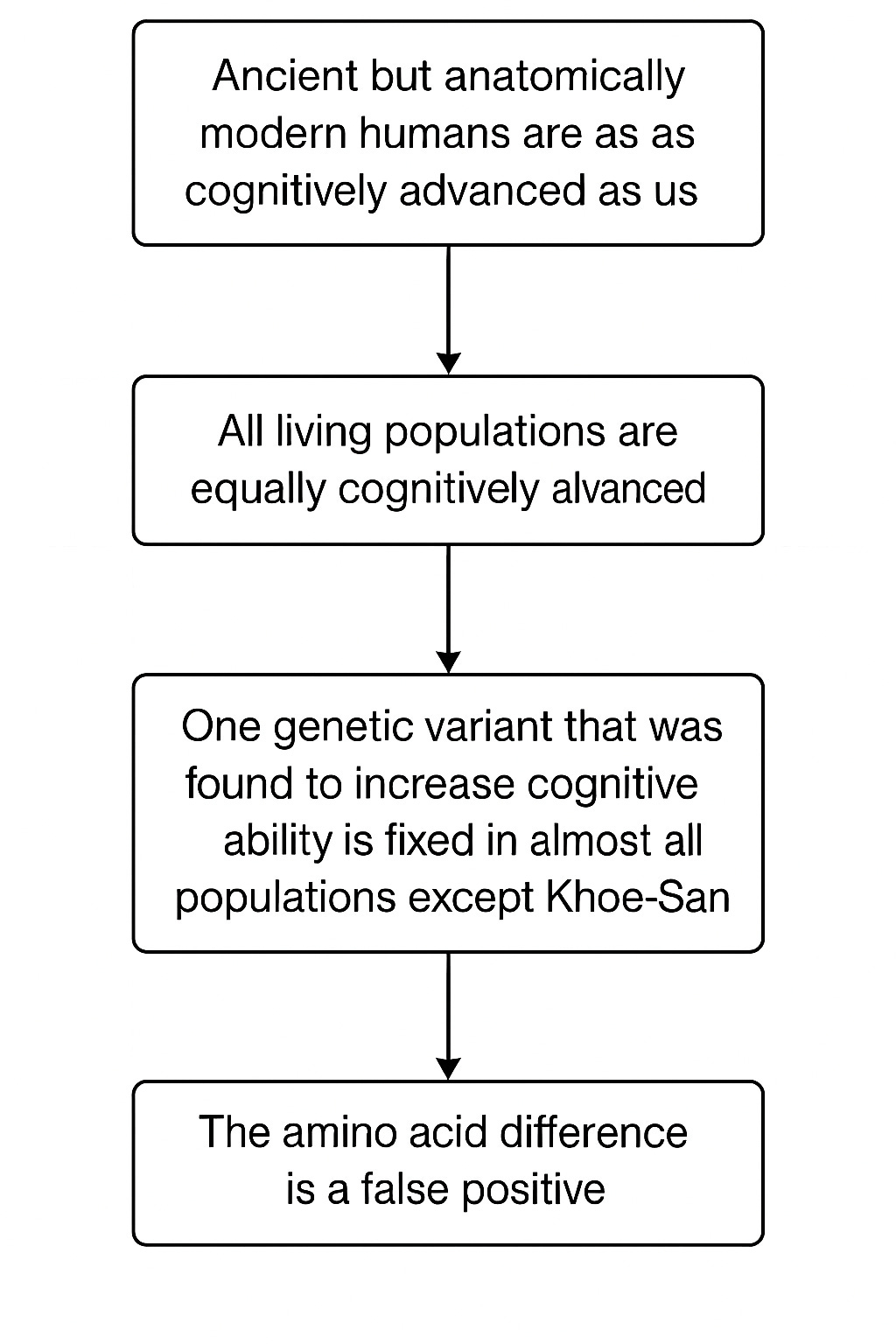

The argument is:

All Homo sapiens populations have equal cognitive potential

A variant that increases cognition must therefore be fixed in all of them

If the variant is not fixed everywhere, it cannot be important

The variant is a false positive

This is a syllogism, not evidence. And the key premise is simply assumed to be true.

Here is the diagram that illustrates this reasoning:

The logic works only if we assume two things at once. First, that all present day populations have the same cognitive level. Second, that selection has acted in the same way on all cognition relevant variants in every population, so that any genuine cognition increasing allele must be close to fixation everywhere. Under those assumptions, a variant that is common in one group but not fixed in all others cannot be important and can be dismissed as a false positive. Both assumptions are at odds with a polygenic view of cognition. Studies that compare polygenic scores across populations show that alleles associated with cognitive and educational outcomes are not at the same frequency everywhere. Some alleles are higher in some groups and lower in others. What matters for the trait is the weighted sum across thousands of variants, not the presence or absence of a single allele. In such a system there is no reason to expect every beneficial variant to be fixed in every population, and no reason to treat a polymorphic variant as irrelevant.

A more empirical approach would treat cognitive related variation as something that can differ between populations, just like height, pigmentation, metabolism or disease resistance. Cognitive traits are polygenic, and polygenic traits evolve. There is no a priori reason to expect uniformity.

The TKTL1 finding is not necessarily a false positive. It is a reminder that cognitive relevant genetic variation within Homo sapiens is real, deep and structured.

Where This Leaves the Sapient Paradox

Once we discard the assumption that cognition was identical across all ancient and modern populations, the paradox collapses. There is no mysterious 100,000 year delay between anatomy and behavior. There is only a long, uneven, polygenic and cultural trajectory.

Jakobsson et al. provide valuable data, but their interpretive framework is tied to a binary model that masks the continuous nature of cognitive and cultural evolution.

Genes changed. Culture changed. Populations diverged.

Behavioral complexity rose unevenly across space and time.

There was never a sapient paradox. There was only evolution.

Thanks. Logic is always essential.