Was Don Quixote Schizophrenic?

What Cervantes Got Right About Psychosis, Sleep, and the Mind

A Literary Diagnosis Through Modern Psychiatry and Genetics

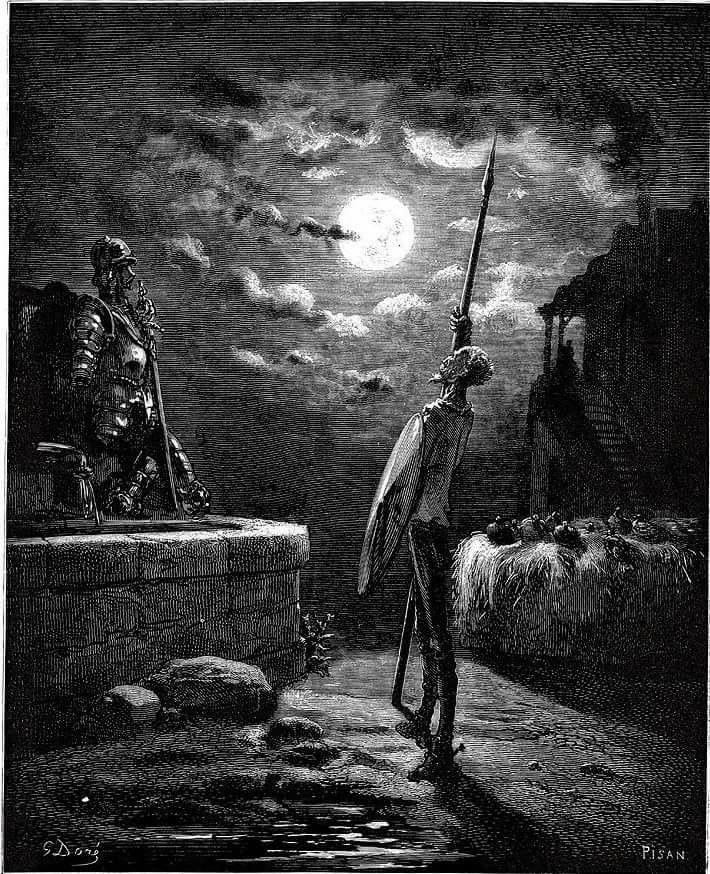

Don Quixote is not an obscure case study. It is one of the most translated and widely read novels in history, often ranked alongside the Bible in global reach and described as a founding work of modern fiction. Cervantes did not just invent a memorable mad knight. He created a character whose inner life has been dissected for four centuries by critics, philosophers, and psychologists.

I also came to Don Quixote from a very specific angle. I have always been drawn to chivalric literature: knight-errant quests, courtly love, impossible vows, the entire world of Amadís and Orlando that Cervantes was parodying. Reading Don Quixote with that background, his “madness” feels less like a comic device and more like a carefully observed clinical portrait, hidden inside a satire of knightly romances.

Diagnosing a fictional character with a modern psychiatric label is always hazardous. Yet Don Quixote is unusually tempting. Cervantes offers not only vivid descriptions of delusion, but also detailed clues about sleep, body habitus, and behavioral rigidity, features that modern psychiatry and genetics now study quantitatively.

This essay does not claim that Don Quixote “had schizophrenia” in a clinical sense. Rather, it asks a narrower and more defensible question:

Do the traits Cervantes emphasized cluster today in individuals with elevated genetic risk for schizophrenia?

1. The core phenotype: fixed false beliefs and loss of reality testing

Cervantes leaves little ambiguity about Don Quixote’s mental state. In the very first chapter, he explains both the content and the rigidity of his beliefs:

“So little sleeping and so much reading dried up his brain, that he lost his wits.”

(Don Quixote, Part I, Ch. 1)

And later:

“Everything he saw he at once converted into something else, as his disordered imagination suggested.”

(Part I)

These are not fleeting misinterpretations. Don Quixote persists in beliefs that are impervious to counter-evidence, a defining feature of delusions in modern psychiatry.

At minimum, this places him somewhere on the psychosis spectrum. Whether that spectrum point is schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or another psychotic syndrome is the question we now explore using ancillary traits.

2. Sleep: deprivation, circadian disruption, and psychosis

Cervantes repeatedly emphasizes chronic night-time wakefulness, not merely poor sleep quality:

“He spent his nights from sunset to sunrise reading… and from so little sleeping and so much reading he lost his judgment.”

(Part I, Ch. 1)

Later, Don Quixote is described as sleeping only a “first sleep”, failing to return to rest, while Sancho sleeps soundly—a classic description of fragmented or curtailed sleep.

Importantly, the text does not describe habitual daytime napping, nor does it portray Don Quixote as lethargic. This distinction is important because modern genetic evidence distinguishes insomnia, chronotype, and napping as separate traits.

Experimental sleep deprivation induces psychosis-like symptoms

A controlled experimental study (Petrovsky et al., 2014) showed that one night of total sleep deprivation in healthy volunteers led to:

Increased perceptual distortions

Increased cognitive disorganization

Reduced prepulse inhibition, a well-replicated biomarker of schizophrenia

This directly supports Cervantes’ intuition: severe sleep loss can precipitate psychosis-like states, even in individuals without a psychiatric diagnosis.

Crucially, this does not mean sleep deprivation causes schizophrenia. It means sleep deprivation can push cognition toward the psychotic end of the spectrum.

2.3 Genetics and Mendelian randomization: insomnia vs chronotype

Large-scale genetic studies refine this picture.

Recent Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses using UK Biobank sleep GWAS instruments (Wang et al., 2022) found:

Morningness (vs eveningness) is associated with lower schizophrenia risk

Daytime napping and long sleep duration show bidirectional associations with schizophrenia

Insomnia, by contrast, often shows no clear causal effect on schizophrenia in MR frameworks

This distinction matters for Don Quixote:

The novel strongly supports extreme night-time wakefulness (behavioral eveningness or circadian disruption)

It does not clearly support habitual napping

His sleep pattern is consistent with circadian misalignment plus sleep deprivation, not classical insomnia complaints

Thus, Don Quixote aligns better with the circadian/behavioral sleep traits genetically linked to schizophrenia than with insomnia per se.

3. Body habitus: thinness, BMI, and schizophrenia genetics

Low Body Mass Index (BMI) has been indicated as a risk factor for Schizophrenia (Sørensen et al., 2006) and patients with SCZ tend to be underweight (Inamura et al., 2012; Sugawara et al., 2018).

Cervantes repeatedly emphasizes Don Quixote’s physique:

“He was of a spare habit, gaunt-featured, and very lean.”

(Part I, Ch. 1)

3.1 Genetic correlation between BMI and schizophrenia

Several large-scale analyses report negative genetic correlations between schizophrenia liability and BMI or adiposity-related measures, meaning:

Alleles that increase schizophrenia risk tend, on average, to be associated with lower BMI.

This does not imply that being thin causes schizophrenia, nor that all individuals with schizophrenia are thin (many gain weight due to antipsychotics). But genetically, baseline liability points in that direction (Bahrami et al., 2020; Rødevand et al., 2023)

In a fictional, untreated pre-modern individual like Don Quixote, the genetic correlation direction is at least concordant with the phenotype Cervantes describes.

4. Pulling the threads together

So what can we actually say about Don Quixote, once we put Cervantes’ text next to modern psychiatry and genetics?

First, the novel itself gives us a surprisingly coherent clinical picture. Across hundreds of pages we see persistent, systematized delusions that do not yield to contradictory evidence, a sustained failure of reality testing, long stretches of night-time wakefulness, clearly fragmented sleep, and repeated hints that the knight is strikingly thin and undernourished. Cervantes did not know the DSM, but he drew a protagonist whose mind and body look very much like a chronic psychotic state.

Second, contemporary science makes this portrait feel less accidental. Experimental work shows that severe sleep deprivation can induce transient psychosis-like experiences in healthy subjects. Large genetic studies find that some circadian traits, such as eveningness and daytime napping, share part of their genetic architecture with schizophrenia, and that higher genetic liability to schizophrenia is associated with lower BMI. Taken together, these lines of evidence make it plausible that Don Quixote’s insomnia and gauntness are not just colorful literary flourishes, but features that sit comfortably inside a modern risk profile for psychotic disorders.

At the same time, there are clear limits to what we can claim. We cannot say that insomnia on its own causes schizophrenia, only that sleep disruption interacts with vulnerability in complicated ways. We cannot pretend that Don Quixote’s particular mix of symptoms uniquely identifies schizophrenia, as if no other diagnosis could fit. And we certainly cannot use genetics to “diagnose” a fictional hidalgo four centuries after the fact. What we can do is more modest and, in some ways, more interesting: show that Cervantes intuitively assembled a character whose traits line up with patterns that are now visible in psychiatric epidemiology and genetic data, without pretending that this alignment turns a literary analysis into a medical chart.

Conclusion

Cervantes did not write a DSM case report. But remarkably, he portrayed a constellation of traits that modern psychiatry and genetics now recognize as clustered rather than random:

psychosis, disrupted circadian behavior, sleep loss, and altered metabolic traits.

Calling Don Quixote “schizophrenic” is anachronistic. But saying that Cervantes intuitively described a mind drifting into psychosis through mechanisms that modern science now partially understands is not.

In that sense, Don Quixote is not a diagnosis, but he is a strikingly modern case study.

References

Bahrami S, Steen NE, Shadrin A, et al. (2020). Shared Genetic Loci Between Body Mass Index and Major Psychiatric Disorders: A Genome-wide Association Study. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(5):503–512. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4188

Inamura Y, Sagae T, Nakamachi K, Murayama N. Body mass index of inpatients with schizophrenia in Japan. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(2):171-181. doi:10.2190/PM.44.2.h

Petrovsky, N., Ettinger, U., Hill, A., Frenzel, L., Meyhöfer, I., Wagner, M., Backhaus, J., & Kumari, V. (2014). Sleep deprivation disrupts prepulse inhibition and induces psychosis-like symptoms in healthy humans. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 34(27), 9134–9140. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0904-14.2014

Rødevand, L., Rahman, Z., Hindley, G. F. L., Smeland, O. B., Frei, O., Tekin, T. F., Kutrolli, G., Bahrami, S., Hoseth, E. Z., Shadrin, A., Lin, A., Djurovic, S., Dale, A. M., Steen, N. E., & Andreassen, O. A. (2023). Characterizing the Shared Genetic Underpinnings of Schizophrenia and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. The American journal of psychiatry, 180(11), 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20220660

Sørensen HJ, Mortensen EL, Reinisch JM, Mednick SA. Height, weight and body mass index in early adulthood and risk of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(1):49-54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00784.x

Sugawara N, Maruo K, Sugai T, et al. Prevalence of underweight in patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:67-73. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.10.017

Wang, Z., Chen, M., Wei, Y. Z., Zhuo, C. G., Xu, H. F., Li, W. D., & Ma, L. (2022). The causal relationship between sleep traits and the risk of schizophrenia: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 399. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03946-8