Why Africans Can Look Closer to the Human–Chimp Ancestor Under Some Metrics

“Closer” here means closer to the inferred human–chimp ancestral state and the result depends on frequency thresholds.

Across online forums and social media, a claim periodically surfaces: “Africans are genetically closer to chimpanzees than other humans are.” The claim is typically presented as if it reveals something profound about human evolution or biological hierarchy.

The claim takes multiple forms. Some versions appeal to phenotypic differences such as cranial measurements, facial morphology, or other anatomical features. Others cite genetic data. This post addresses only the genetic version: what ‘closer to chimp’ means when measured by allele frequencies at polarized sites. I won’t be discussing morphological or phenotypic comparisons here. What I will show is that when the genetic claim is traceable to real data at all, it describes a subtle pattern in allele frequency distributions that follows straightforwardly from human demographic history.

Once the claim is translated into that language, it becomes much easier to evaluate, and it becomes clear why it can be true under some metrics while being misleading under others.

What “closer to chimp” means if the data are allele frequencies

In this post, “chimp” is just an outgroup used to label each SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism) as ancestral or derived at the human–chimp split (more precisely: the allele inferred to be present in the human–chimp last common ancestor). Once you do that, a human population’s derived allele frequency (DAF) is simply the frequency of the non-ancestral state at that site.

If you then build a frequency-weighted distance to the outgroup, the logic is straightforward: chimp is typically fixed for the ancestral allele, so the distance grows mainly when the derived allele becomes moderately common or high-frequency in humans. Rare derived variants contribute very little to a mean-DAF style metric, while common derived variants contribute a lot.

So “closer to chimp” in these summaries usually reduces to a simpler statement:

Lower mean DAF at polarized sites = closer to the inferred ancestral state (because the outgroup is ancestral at those sites).

Under that interpretation, “Africans look more ancestral” means: at many polarized loci, the ancestral state is at higher frequency in AFR, equivalently the derived state is at slightly lower frequency, which can reduce a frequency-weighted distance to the outgroup, especially when you focus on alleles that are present at non-trivial frequency.

Disclaimer (ancestral state): In 1000 Genomes, the “ancestral allele” label (INFO/AA) is inferred from multi-primate alignments/ancestral reconstruction (Ensembl EPO) rather than read off chimp alone. In other words, “chimp” here is shorthand for the inferred human–chimp ancestral state at each site. Like any polarization step, this annotation is not perfect, so a small amount of misassignment is expected.

The first thing to check is whether the pattern is real or an artifact

A major trap is SNP ascertainment bias. Many SNP arrays were built from discovery panels that were not globally representative. That can distort the allele-frequency spectrum differently across populations.

A nice demonstration is in Kim et al. (2018): using 1000 Genomes whole-genome sequencing (WGS), mean DAF for non-disease SNPs is similar across continental groups, but using common genotyping arrays, derived allele frequencies in African populations can look markedly lower than in non-Africans because of how the SNPs were chosen (Kim et al., 2018).

This is important because a large fraction of online discourse unknowingly compares array-ascertained SNP sets and treats the result as “genome-wide biology.”

What whole-genome data actually support

Africans have more variant sites overall

The 1000 Genomes Phase 3 paper reports that individuals from African-ancestry populations harbor the greatest numbers of variant sites per genome, as predicted by out-of-Africa demography (The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2015).

Africans are enriched for rare derived alleles

The cleanest way to express the “chimp similarity” intuition is through the unfolded site frequency spectrum (SFS), which tracks the distribution of derived allele frequencies.

Keinan et al. (2007) explicitly report that West Africans (YRI) have more rare derived alleles than expected under a constant-size model, consistent with population expansion, while non-Africans show a deficit of rare derived alleles consistent with a bottleneck.

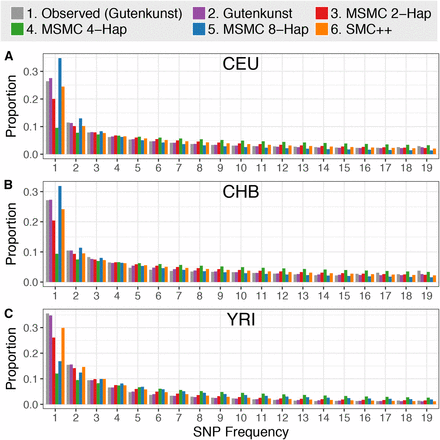

A separate analysis using 1000 Genomes data plots the unfolded proportional site-frequency spectrum (SFS) for CEU (Utah residents with Northern/Western European ancestry), CHB (Han Chinese in Beijing), and YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria), showing clear differences in the shape of the spectrum across these populations (Beichman, Phung, & Lohmueller, 2017) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The quantity that really matters in these debates is not the unweighted count of derived variants, but the frequency-weighted summary, such as mean derived allele frequency (mean DAF) across a fixed set of polarized sites. Mean DAF is what an allele-frequency-based resemblance-to-outgroup statistic is tracking, because it weights common alleles more than rare ones. In contrast, simply counting derived variants gives the same weight to a singleton and to a 40%-frequency allele, which can create a misleading impression that the population with more rare variants is “more derived,” even when those variants contribute little to mean DAF.

Africans have more singletons in the unfolded SFS, so an unweighted “how many derived sites exist” count will inflate their apparent “derivedness,” while mean DAF can still be lower if much of that extra mass sits in the rare bins.

The WGS literature emphasizes that the out-of-Africa bottleneck changes genotype configurations, with African genomes more likely to be heterozygous for derived alleles and non-African genomes more likely to be homozygous for derived alleles (Kim et al., 2018).

Below the paywall: I compute mean DAF on a shared locus set across 1000 Genomes superpopulations, split the result into three panels (zeros vs DAF ≥ 1%), and test the differences . This is where the “Africans look more ancestral” pattern becomes sharp, and why the DAF ≥ 1% lens is the more phenotype-relevant one.