Your Genome Is an Archaeological Site, But We’re More Than a Mosaic of Ancestries

How ancient layers persist, and how selection reshaped them

When people talk about ancient ancestry, they usually talk about populations. Italians have roughly this much Neolithic farmer ancestry. Northern Europeans tend to have more Steppe-related ancestry. Parts of the eastern Mediterranean tend to show more ancestry ultimately related to ancient Near Eastern and Caucasus/Iran Neolithic–adjacent sources. These summaries are convenient, but they quietly hide a fact that matters more than the averages: ancient ancestry is not evenly distributed across individuals.

Two people born in the same country, in the same decade, and living in the same city can still carry noticeably different amounts of Western Hunter-Gatherer, early farmer, or Steppe-related ancestry. Thousands of years of mixing blurred those contrasts, but it did not erase them. Ancient migrations survive today not as clean labels stamped onto whole nations, but as uneven layers inside individual genomes.

Biology does not act on population averages. Selection acts on individuals, and individuals inherit different subsets of ancient genetic variation. When we collapse everything to national or regional means, we throw away real signal and sometimes manufacture false ones. Variation in traits linked to health, longevity, and polygenic scores can exist within a country partly because deep ancestry still varies between people inside that country.

In this post, I argue that your genome is best understood as an archaeological site: a stack of layers belonging to different evolutionary periods, reshuffled and fragmented, but still present in uneven amounts from one country to the next, and even from person to the next! Using evidence from three recent studies that infer genome-wide ancient ancestry across many present-day populations, I show why deep ancestry did not become fully homogeneous with time, how we can detect the remaining individual-level variation, and why taking these layers seriously changes how we interpret genetic associations and evolutionary signals today.

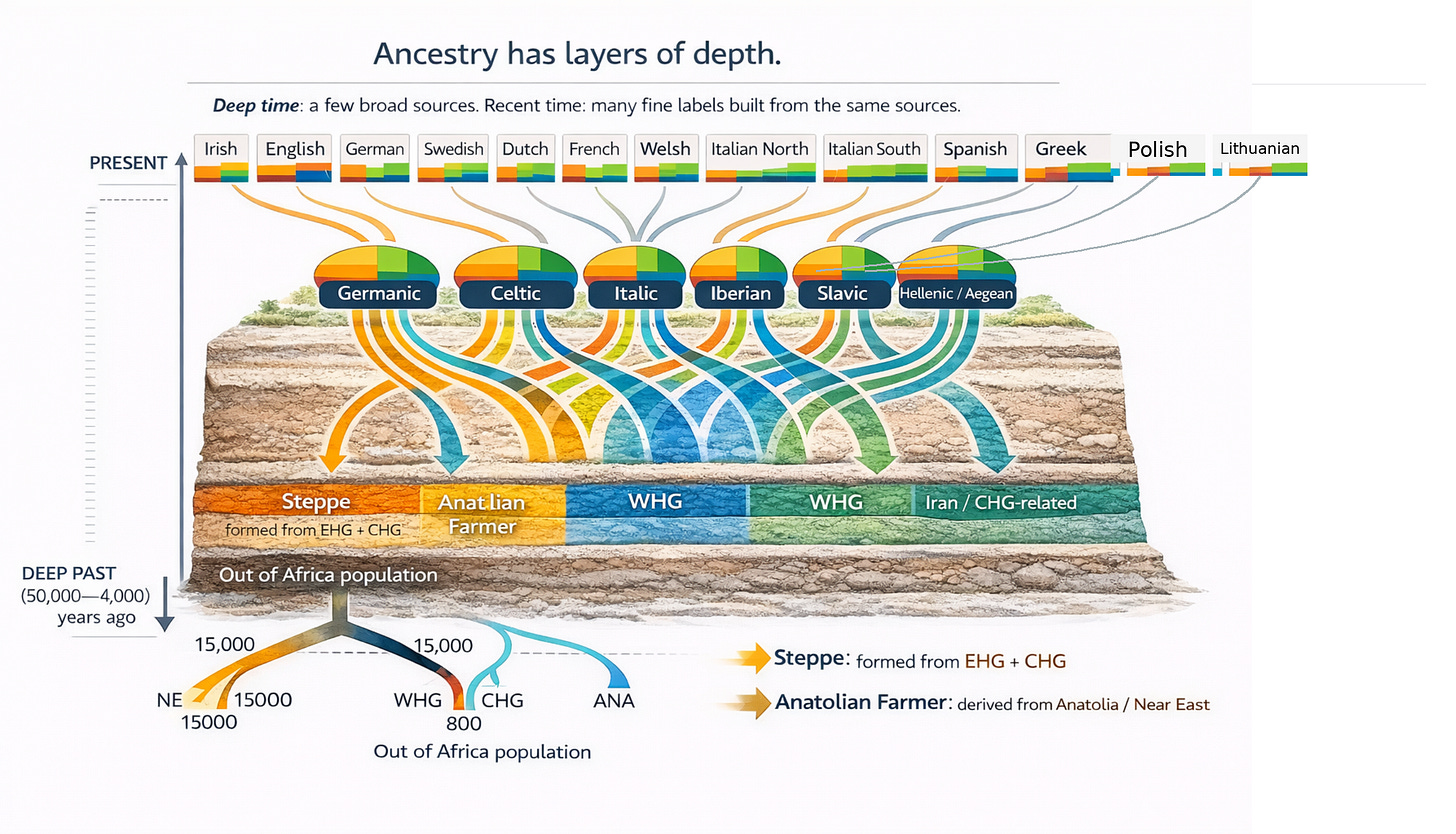

To make this intuition concrete, Figure 1 visualizes ancestry as a set of layers with different depths in time. The top row shows present-day national populations, the middle row groups them into broader recent ancestry families, and the lower layers represent increasingly deep ancestral sources shared across Europe and West Eurasia. The flowing streams emphasize that recent population labels are built from the same ancient components, combined in different proportions and at different times.

Importantly, the relative proportions shown in the figure are purely illustrative. They are not meant to represent precise ancestry fractions for any population. The goal is conceptual rather than quantitative: to show how a small number of deep ancestral sources give rise to many modern populations, and how these sources persist as overlapping layers rather than disappearing through complete homogenization.

What matters is not the exact thickness of any layer, but the structure itself: ancestry is stratified in time, unevenly distributed across individuals, and recombined into many fine-grained modern labels from a shared set of deep components.

A chunky blend, not a clear juice

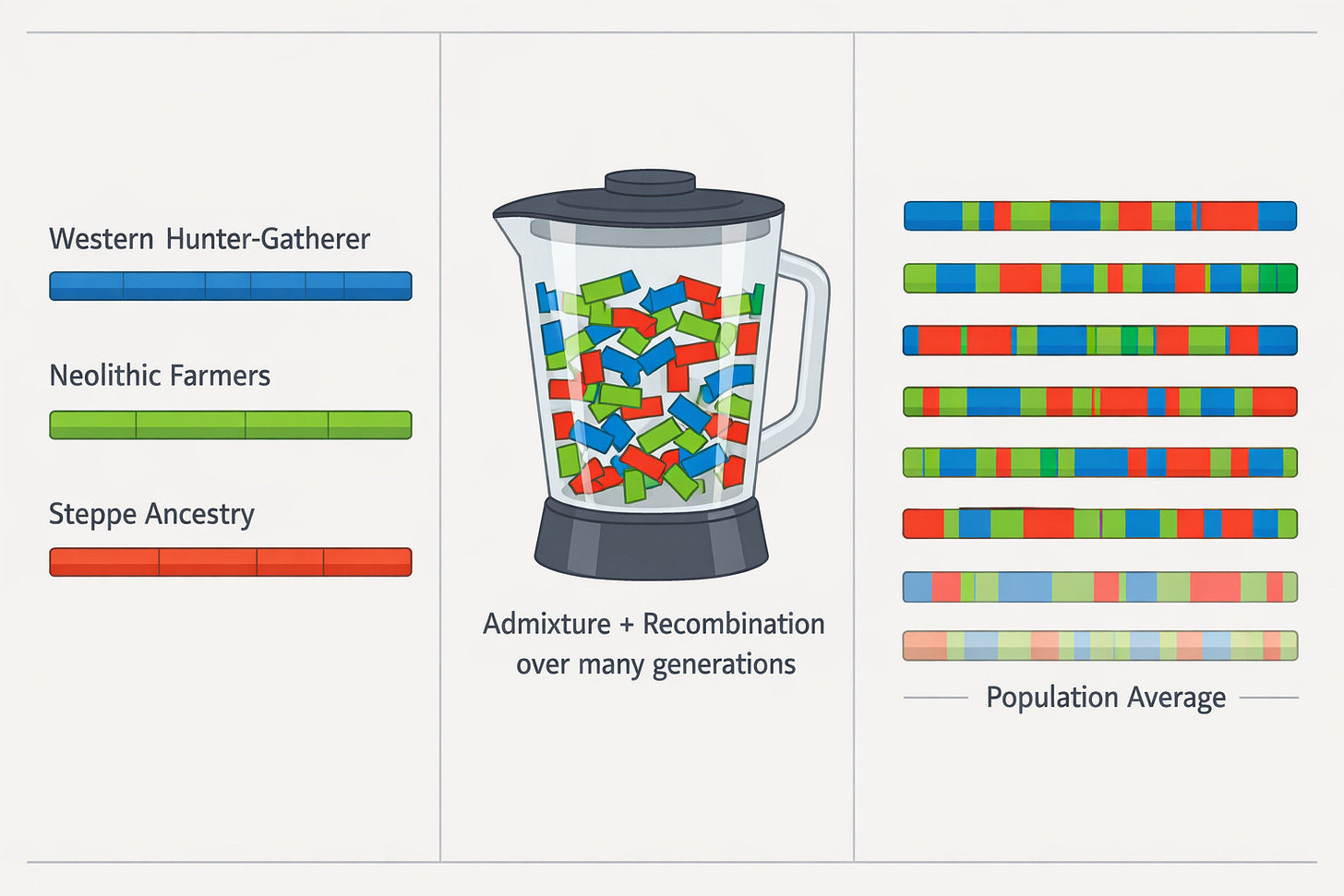

Even after hundreds of generations, deep ancestry can still vary among individuals because mixing does not blend genomes into a uniform average. DNA is inherited in discrete chunks from a limited set of recent ancestors, not as a smooth population-wide mixture. Two people can share the same national background yet inherit different combinations of ancient segments simply because their family histories followed different paths. Recombination breaks ancestry into smaller pieces over time, but it never guarantees that everyone ends up carrying the same mix. Add in geography, social structure, and non-random mating, and individual genomes remain uneven mosaics of ancient lineages long after population averages have stabilized.

Think of deep ancestry as a chunky blend, not a clear juice. Admixture chops ancient DNA into smaller pieces over time, but it does not dissolve it. Each person inherits a different handful of fragments from a limited set of ancestors, so individual genomes remain uneven mosaics long after population averages stabilize. This is shown in the figure below: