Cold Winters, Academic Achievement and Income in Italy

Climate, ancestry, and cognitive outcomes at the municipal level

In a previous post I tested variants of the Cold Winters hypothesis using ancient DNA and cross-population comparisons. Those analyses suggested a recurring pattern: populations exposed to harsher winter environments tend to have higher cognitive polygenic scores, albeit the effect was relatively small.

The real question is methodological: are we confusing ancestry structure with selection? When you work with aDNA you are not comparing nations or ethnic groups. You are comparing individuals and archaeological populations that differ in date, geography, and mixture history, using polygenic scores and principal components computed from the genomes themselves.

The worry is that apparent climate effects can arise because colder and warmer regions have different ancestry compositions, and polygenic scores can correlate with ancestry for many reasons unrelated to selection (drift, migration, sampling, imperfect GWAS portability, and so on). The hard problem is separating an ecological gradient from population structure.

At the same time, there is also the opposite risk: overcontrolling. If selection really acted in certain environments, then ancestry and climate will partly line up, and aggressively partialling out structure can erase part of the signal.

This tension motivates looking at a simpler setting: a single country with shared institutions, where we can ask whether climate still predicts outcomes once demographic history is taken seriously.

Measuring winter severity directly: gradi-giorno

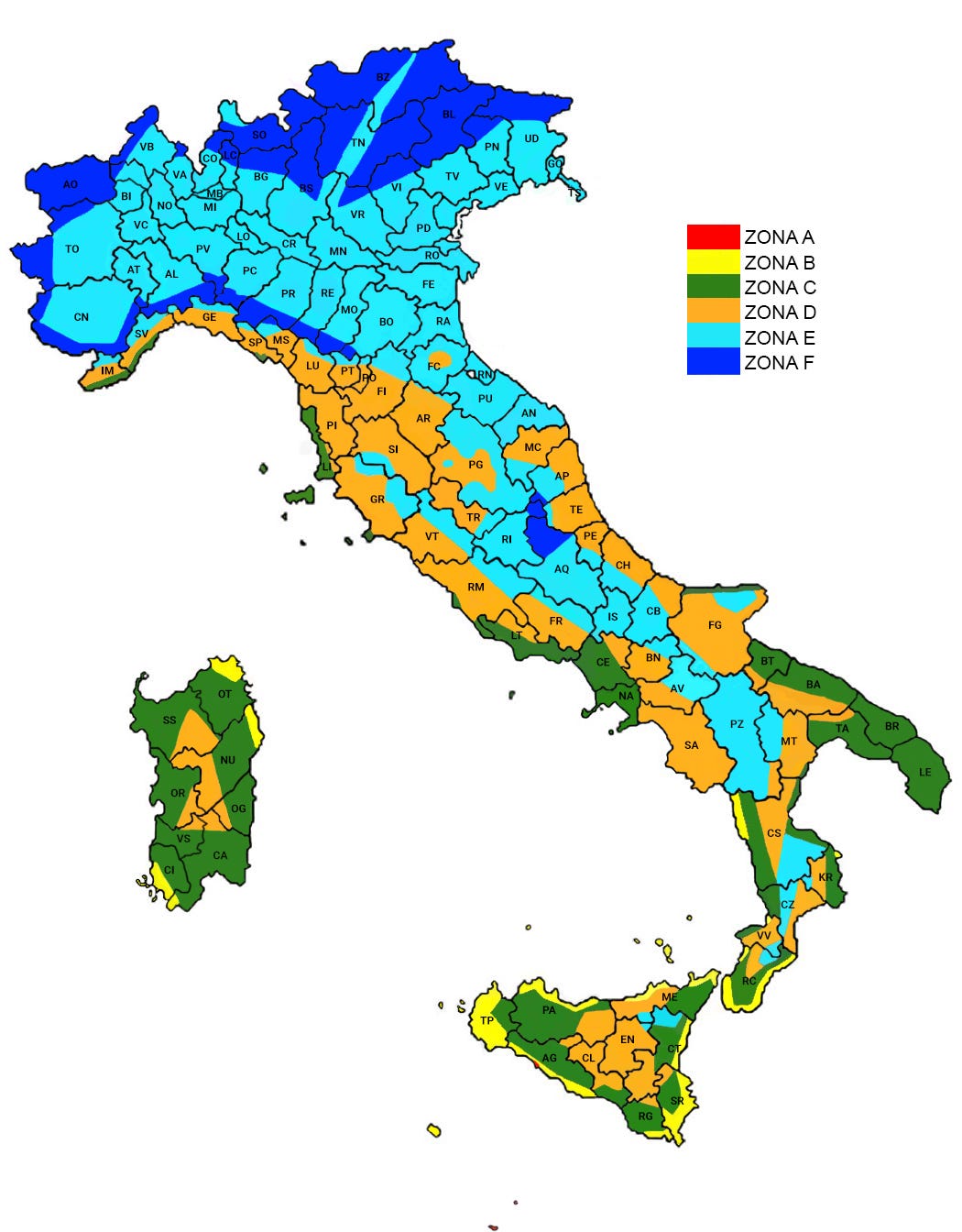

As the chief climatic variable I use gradi-giorno, the metric employed by the Italian state to regulate heating.

In simple terms, it works like this. For each day of the year, you take a reference indoor comfort temperature (20 °C). If the outdoor mean temperature is lower, you count the difference. A day with an average of 5 °C contributes 15 degree-days; a day at 18 °C contributes 2; a day above 20 contributes zero. Add this across the year.

Places with cold, long winters accumulate large totals. Mild places accumulate small ones.

So this isn’t a climate index I constructed for the analysis. Gradi-giorno is an administrative measure designed for a practical purpose: quantifying how demanding winter is in day-to-day life, via heating needs. On this basis, Italy is officially classified into six heating zones (A–F), and those zones determine key rules, such as when and for how many hours per day heating systems can operate.

Controlling ancestry without genomes: surnames

We do not have genetic principal components for every municipality. But surnames carry information about demographic history. They are inherited, geographically clustered, and shaped by migration and isolation.

Using the approach described in Piffer et al. (2025), municipal surname distributions can be used to estimate how similar a comune is to historically northern versus southern Italian provinces. It is not DNA, but it is a reasonable proxy for population structure when genomes are unavailable.

Think of it as ancestry control with different data.

Outcomes and model

The main outcome is school performance from standardized INVALSI tests.

I run the same specification twice, once with school performance and once with per-capita income. The second model is not meant to “explain away” education through wealth; it provides a comparison. If climate is merely standing in for development, we should see it operate more strongly on income than on test results.

Predictors:

winter severity (gradi-giorno)

altitude

surname-based north/south admixture

population size

A key detail: the climate variable is residualized on admixture, altitude, and population. This forces it to represent the part of winter harshness that is not simply the demographic gradient under another name, and it keeps collinearity low.

In other words: once you control for the north–south demographic structure, is there still anything left for climate to explain?

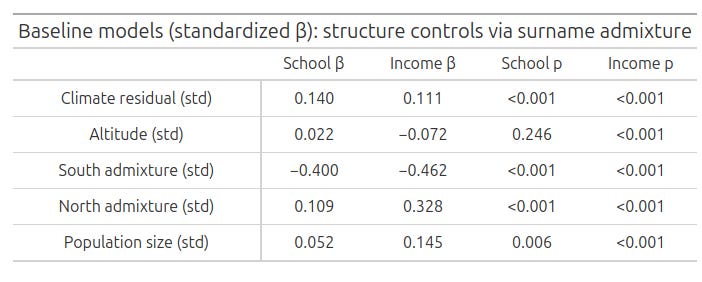

Regression results

The dominant pattern is demographic. Even within one country, surname-inferred ancestry strongly predicts both income and school outcomes. Ignoring that would obviously confound any ecological analysis.

But climate does not vanish once those controls are included.

Municipalities that are colder than expected given their surname profile, altitude, and size tend to show better school performance. The standardized effect is modest (around β ≈ 0.14) compared with the ancestry gradient.

Income shows a similar association, though slightly smaller (β ≈ 0.11).

Altitude, meanwhile, contributes to income but not to test scores once the rest is in the model. That is intuitive: mountain areas can face economic disadvantages. Yet altitude itself is not the mechanism usually invoked by Cold Winters arguments. Winter severity is.

Because climate has been residualized on the demographic predictors, diagnostics show essentially no collinearity. The model is explicitly asking whether climate adds explanatory power beyond migration history.

Genetic selection, culture, or immediate environment?

The key question is why the surname controls do not absorb the entire education gradient. Under a genetic or cultural transmission model, surnames—being inherited and geographically clustered—should capture a large share of persistent differences, especially since there has been little time for biological evolution over the last few centuries.

There are two broad explanations. First, the climate term could reflect a transient environmental effect: hotter conditions may depress performance directly through heat stress, sleep, classroom comfort, or seasonality. In that case, climate matters now even if surnames fully capture inherited structure.

Second, the surname proxy may simply be too coarse. A north–south “admixture” score captures major demographic history, but Italy contains substantial climatic variation within each macro-area. If the controls mostly remove the national north–south gradient while leaving finer-scale structure unmodeled, a residual climate association can remain, whether the underlying within-region structure is neutral ancestry, persistent cultural differences, or geographically patterned genetic predispositions.

This is why region fixed effects, or North–Center–South fixed effects with interactions, are a useful robustness check. They force the climate coefficient to be identified within areas, not by differences between broad parts of Italy.

The demographic gradient is large, as expected. But what happens to climate after we force the comparison within regions?