Why Northern Europeans Seem Aloof and Southern Europeans Outgoing

If you’ve spent time moving across Europe, you’ve probably noticed a pattern. In the south, conversation often gets going a little more quickly: people speak a bit more openly, gesture more, and pause less. Further north, interaction can be more reserved. Small talk is less automatic, and silence is treated as normal rather than something to avoid.

Then there are the familiar exceptions. The Irish are famously warm and talkative despite living far north, while Finns are famous for the opposite.

These are well-worn stereotypes, and we’re often told not to take them seriously. But stereotypes don’t usually persist for centuries unless they’re capturing something real at the population level. Individuals vary widely, obviously, but why do the same regional patterns keep showing up even as politics, religion, and institutions change?

This post explores one underexamined factor: genetic differences in population-level predispositions related to sociability and extraversion.

Where the numbers come from

Before we look at the map, it’s worth being concrete about what I actually did.

I used a published GWAS of extraversion (Gupta et al., 2024) to construct a polygenic score (PGS), defined as a weighted sum of trait-associated alleles across the genome, with weights given by GWAS effect sizes. The GWAS was conducted in the Million Veteran Program (MVP), using individuals of European ancestry.

Then I applied that scoring model to personally curated genotype data, grouped individuals by country, and computed country-level averages. The scores were centered so that the mean for White British individuals is zero.

A genetic gradient you can see on a map

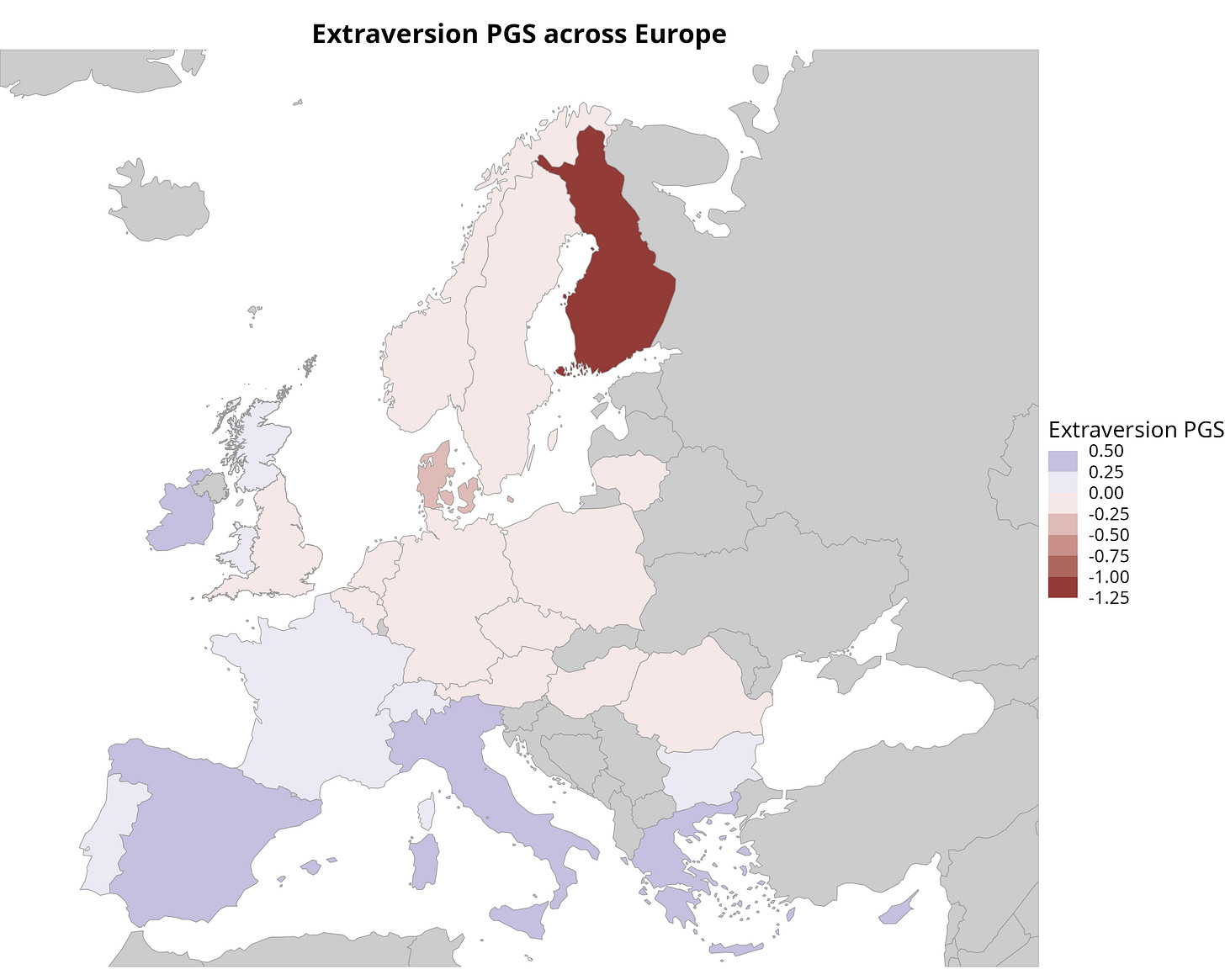

The map below shows Europe colored by the standardized extraversion PGS, averaged by country. Countries without data are grey. I also compress extreme outliers visually so the mid-range variation (where most countries lie) is easy to see.

What stands out immediately is not a sharp divide, but a smooth gradient.

Southern Europe — Spain, Italy, Greece — tends to sit higher on the scale. Northern and northeastern Europe tends to sit lower. Finland, in particular, is at the low end. Ireland, conspicuously, is not.

North–south: the obvious pattern

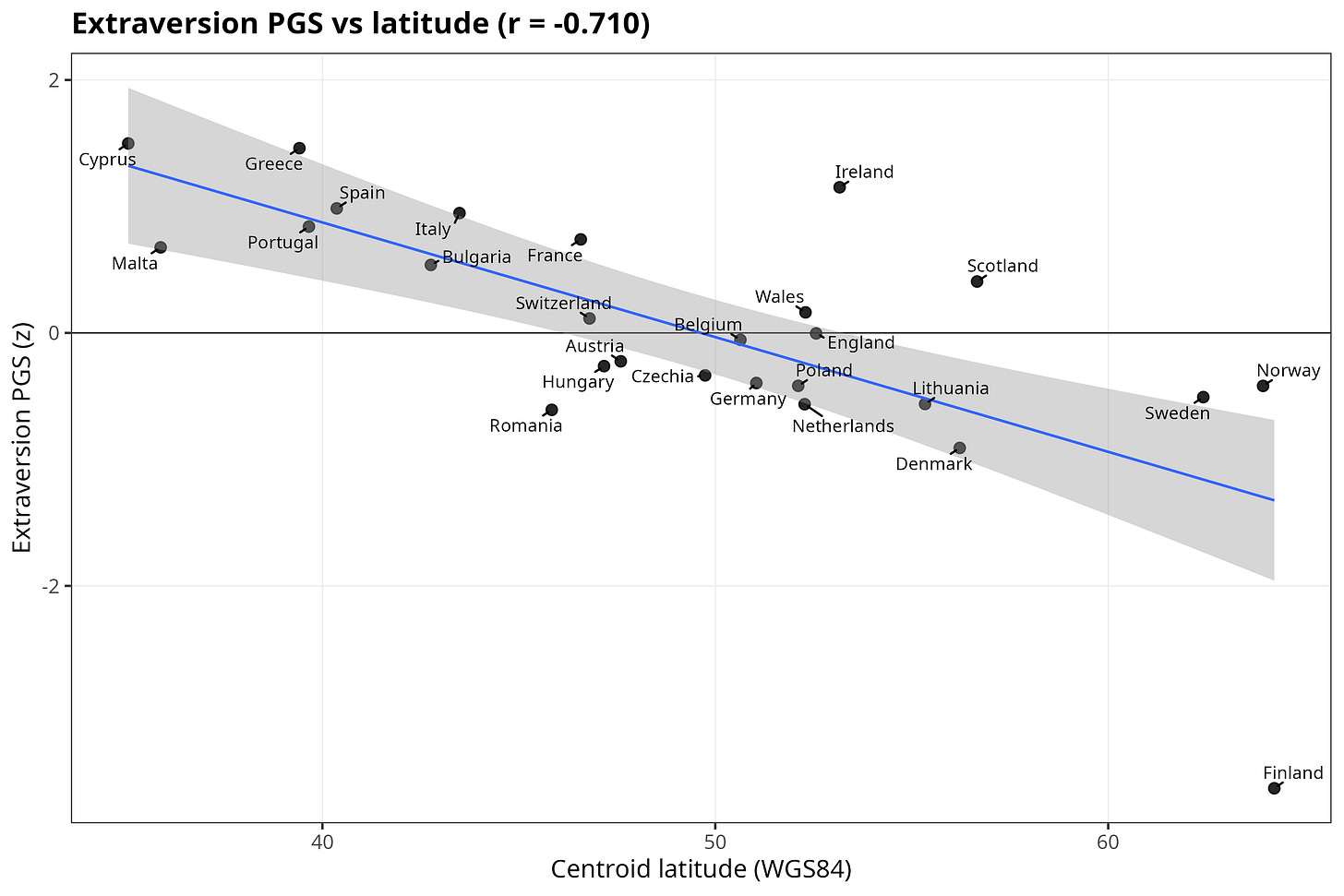

I used polygon centroids to assign each country a latitude and longitude. That’s not ideal: the “average person” in a country isn’t located at the geometric center, so population-weighted coordinates would be more accurate.

Then, I plotted the same country averages against latitude:

The relationship is clear: as latitude increases (the furthern north you go), the extraversion PGS tends to decrease.

That already mirrors a familiar cultural contrast. Northern Europe is often described as more emotionally restrained, more socially distant, more private. Southern Europe as more expressive, outward-facing, and socially intense.

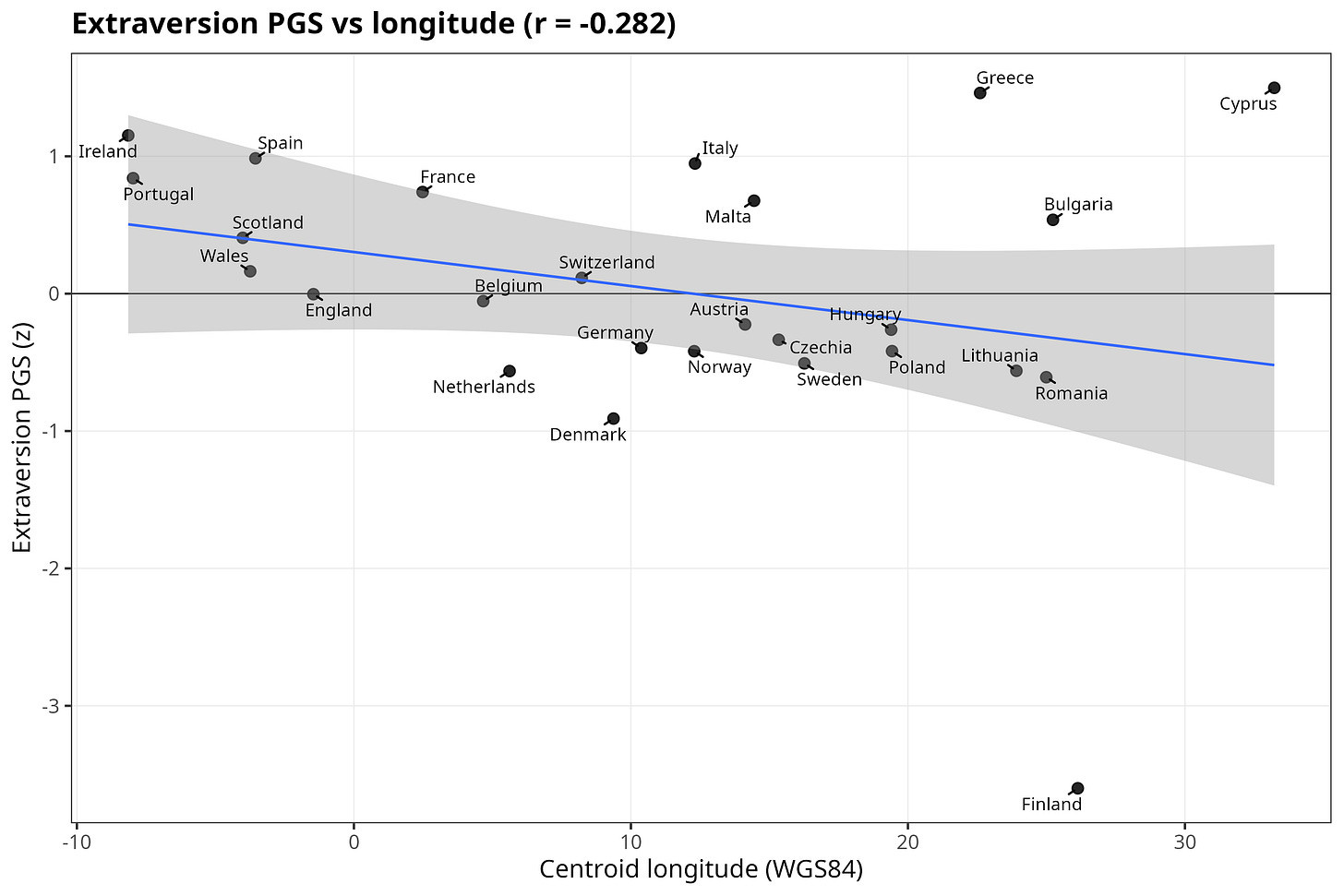

East–west: why Ireland isn’t Finland

If latitude were everything, Ireland and Finland should look similar but they don’t.

Ireland scores much higher than its latitude would predict. Finland scores much lower. These deviations line up almost perfectly with cultural intuition.

To see why, the plot below shows the same PGS against longitude.

An east–west pattern shows up alongside the north–south one. At similar latitudes, western populations tend to score a little bit higher on the extraversion PGS than eastern ones. That helps explain why the “reserved North” stereotype fits Finland far better than Ireland, even though both are northern.

Europe’s behavioral landscape has a north–south structure, but it also has east–west structure, and their interaction produces exactly the kinds of regional exceptions people intuitively recognize.

The east-west gradient, however, is much weaker, as shown by the much smaller correlation with longitude than latitude (0.28 vs 0.71).

Genetic predispositions and cultural patterns

For decades, explanations of European behavioral differences have focused on climate, religion, institutions, and recent history. Those frameworks can describe how norms are maintained and transmitted. They struggle to explain why certain social styles feel effortless in some regions and strangely taxing in others, or why the same gradients persist across centuries of political and economic change.

Population-level polygenic gradients don’t replace cultural explanations. But they add something: small differences in predisposition can bias which norms feel natural, which interaction styles get rewarded, and which social equilibria become stable. Culture then amplifies and formalizes what began as weak statistical tendencies.

That’s why, even in a modern, mobile, globalized Europe, some old stereotypes still ring true.

References

Gupta, P., Galimberti, M., Liu, Y. et al. A genome-wide investigation into the underlying genetic architecture of personality traits and overlap with psychopathology. Nat Hum Behav 8, 2235–2249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01951-3

Where exactly do these polygenic scores come from?

I ask because such a result could easily be circular, depending on the methodology — if one did PGS analysis using all of modern Europe, for example, the fact that there are more introvertsin the dataset in Finland would itself tend to cause more of their genes to be classified as introverted. That could happen even if the explanation were actually cultural. Of course, that circularity could be headed off by creating PG scores based on, for example, only a British population. But the method used seems very important and the perfect-correlation map makes me suspicious.

What is the method used for these?