A Debate on Race and Genomic Prediction: Geneticist vs. Heterodox Leftist Logician

Reflections on a debate between Barbujani, Odifreddi, and Barbero

As Italy follows the Milano–Cortina Winter Olympics and celebrates a run of gold medals at an improbable pace, three intellectual heavyweights gathered, largely outside the sporting spotlight, for a very different kind of contest. The event brought together Guido Barbujani, a population geneticist; Alessandro Barbero, the country’s best-known historian; and Piergiorgio Odifreddi, a logician and philosopher of science.

Barbero is a genuine celebrity with a following far beyond academia. Odifreddi is a familiar face to anyone who has watched Italian debates for the last two decades. Barbujani is less of a household name, but he is one of Italy’s most visible public geneticists, and in this conversation he plays the crucial role.

The relevant part of the discussion is available here (in Italian):

Ironically, Odifreddi, whose politics are firmly in the progressive camp (pro-Palestinian, feminist, atheist, etc.), found himself advancing points that align with race realism. Barbujani, by contrast, defended what has become the mainstream (politically correct) formulation in modern human genetics: variation exists, sometimes visibly and medically relevant, but it does not divide humanity into discrete biological races. Barbero, acting as moderator, repeatedly reminded the audience that the historical uses of the word “race” concern systems of discrimination that required no sophisticated biological justification in the first place.

Barbujani starts on the wrong foot

Barbujani starts on the wrong foot by opening with a familiar metaphor: the genome as a 6.5-billion-letter text whose “grammar” we partly understand but whose “syntax” still escapes us. From that he draws a reassuring conclusion: even if we read your entire genome, we still cannot predict whether you will get cancer or diabetes, or even how tall you will be.

That made sense twenty years ago. Today it's patently false.

Modern GWAS and polygenic scores do not give deterministic answers, but they do predict complex traits with non-trivial accuracy, and the accuracy varies dramatically by phenotype. Height is the canonical example: in European cohorts, polygenic predictors now explain roughly half of the variance, translating into typical individual prediction errors on the order of about five centimeters (Yengo et al., 2022). Prediction for cognitive traits is weaker, noisier, and more ancestry-dependent, but it is far from zero. This isn’t just academic anymore: polygenic embryo screening is already being offered for height, IQ, and disease risks such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s.

Barbujani’s contrast between “we can read but cannot predict” is therefore outdated. The more accurate statement today is narrower: prediction is imperfect and it travels unevenly across ancestries, yet it is already informative enough that prospective parents can rank embryos by expected traits.

He then pivots to the evening’s core issue. Speaking of human races, he argues, is essentially “improponibile”, unacceptable in contemporary biology.

A fixation on fixation

A key claim in Barbujani’s intervention is that if biological races existed in any strong sense, we should be able to find variants that are universally present in one group and universally absent in another. Because such cases are said to be vanishingly rare, the concept is dismissed.

But that standard is not applied consistently elsewhere in biology. Consider the Marsican brown bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus), a small, isolated population in the central Apennines that has long been treated as a distinct subspecies. I wrote a piece on it here:

Under Barbujani’s criterion, this classification would be hard to justify. The Marsican bear is not separated from other brown bears by a single universally fixed “diagnostic” mutation. Its distinctiveness is the ordinary kind produced by isolation and drift: genome-wide frequency shifts, extreme bottlenecks, low diversity, and a recognizable cluster of haplotypes and allele frequencies relative to other European brown bears. Yet taxonomists do not conclude, “Since there is no single site where all Marsican bears have X and all other bears have Y, the subspecies does not exist.” They infer lineage structure from the total pattern.

This applies more broadly. Hybridization and introgression are well documented even between recognized species (e.g., polar and brown bears) (Cahill et al., 2015; Lan et al., 2022), and in classic “porous species boundary” systems like Heliconius (Brower, 2013). If Barbujani’s fixation-based standard were enforced consistently, a non-trivial fraction of contemporary taxonomy would collapse into “everything is too mixed to classify.”

Odifreddi’s argument: fuzziness doesn’t abolish categories

Odifreddi’s most serious intervention is easy to underestimate because he delivers it with jokes and provocations. But underneath, he is pressing a precise point.

He reminds the audience that biological categories are rarely sharp. Species, subspecies, varieties: these are what logicians call fuzzy concepts. The tadpole becomes a frog; the endpoints are clear, the transition is gradual. Yet biologists keep the words because nature gives us continua, not clean breaks.

Why, then, should fuzziness suddenly become disqualifying only for humans?

But Odifreddi doesn’t stop at philosophy. He also pushes an empirical challenge. If differentiation is real, he asks, can it sometimes be detected genetically? He mentions the famous Y-chromosome lineages associated with Jewish priestly descent — the so-called “chromosome of Aaron” — as an instance where ancestry correlates with identifiable markers.

The point is not that this creates a perfectly bounded, homogeneous group. The point is that genetics routinely works with probabilistic clustering, not absolutes.

And that is already how ancestry inference operates in practice. Commercial testing companies such as 23andMe assign individuals, with high but never perfect probability, to clusters labeled Ashkenazi Jewish, Italian, Japanese, and so on. No one imagines these assignments require universal, exception-free markers. They rely on patterns of correlated frequencies across many loci.

So Odifreddi’s challenge to Barbujani is straightforward: if biology everywhere else tolerates blurred edges and statistical membership, why demand immaculate boundaries here?

“No sharp line” does not mean “no structure.” It means the structure will be approximate, which is precisely the terrain where population genetics normally lives.

“Why ‘99.9% the same’ misleads”

Humans, Barbujani emphasized, differ on average by roughly one nucleotide in a thousand. The implication is clear: whatever differences we observe, they are numerically small when measured against the overwhelming background of shared genetic material.

The '0.1%' figure refers to an average across millions of genomic positions.

The same rhetorical move shows up in human–chimp comparisons: the famous “98–99% identical” figure counts only substitution differences in the parts of the genome that align cleanly. It’s a narrow metric that can make meaningful biological divergence sound trivial.

Human groups may differ only slightly in absolute terms at any given locus, yet if many loci shift in frequency in a coordinated fashion, those shifts become highly informative. This is why principal component analyses reproduce geography, why clustering algorithms achieve high assignment accuracy, and why ancestry inference is possible even though virtually no single marker is decisive on its own.

Differentiation is not caused only by how many letters differ; it is also about how differences covary.

Barbujani’s “Not a single case”

At one point Barbujani delivers what is rhetorically the knockout punch of the evening. After invoking hundreds of thousands of polymorphic sites and “hundreds of millions of comparisons,” he tells the audience that no one has ever found a case in which one human population has one thing while another human population is entirely homogeneous and has another thing. The moral follows immediately: we are deeply mixed, therefore the biological idea of race collapses.

But this claim is ambiguous. Read literally, this means that there are no loci where an allele is present in one population while another population carries none of it and is therefore homogeneous for the alternative state.

Read this way, it's simply false: such loci are common and include some of the most familiar variants in human genetics.

A straightforward example is rs12913832 in the HERC2/OCA2 region, one of the best-known variants associated with blue versus brown eyes.

Here Odifreddi had suggested a more cautious but naive position. Perhaps, he said, we simply do not yet know the genes responsible for visible differences such as skin pigmentation. If one day those variants were identified, they might well serve to demarcate different races.

But this is not a hypothetical future. For many traits, the variants are already known.

It is telling that Barbujani never corrects him on this point!

Variants in genes such as SLC24A5 (e.g., rs1426654) show large, well-characterized frequency differences across populations and explain a meaningful share of skin color differences.

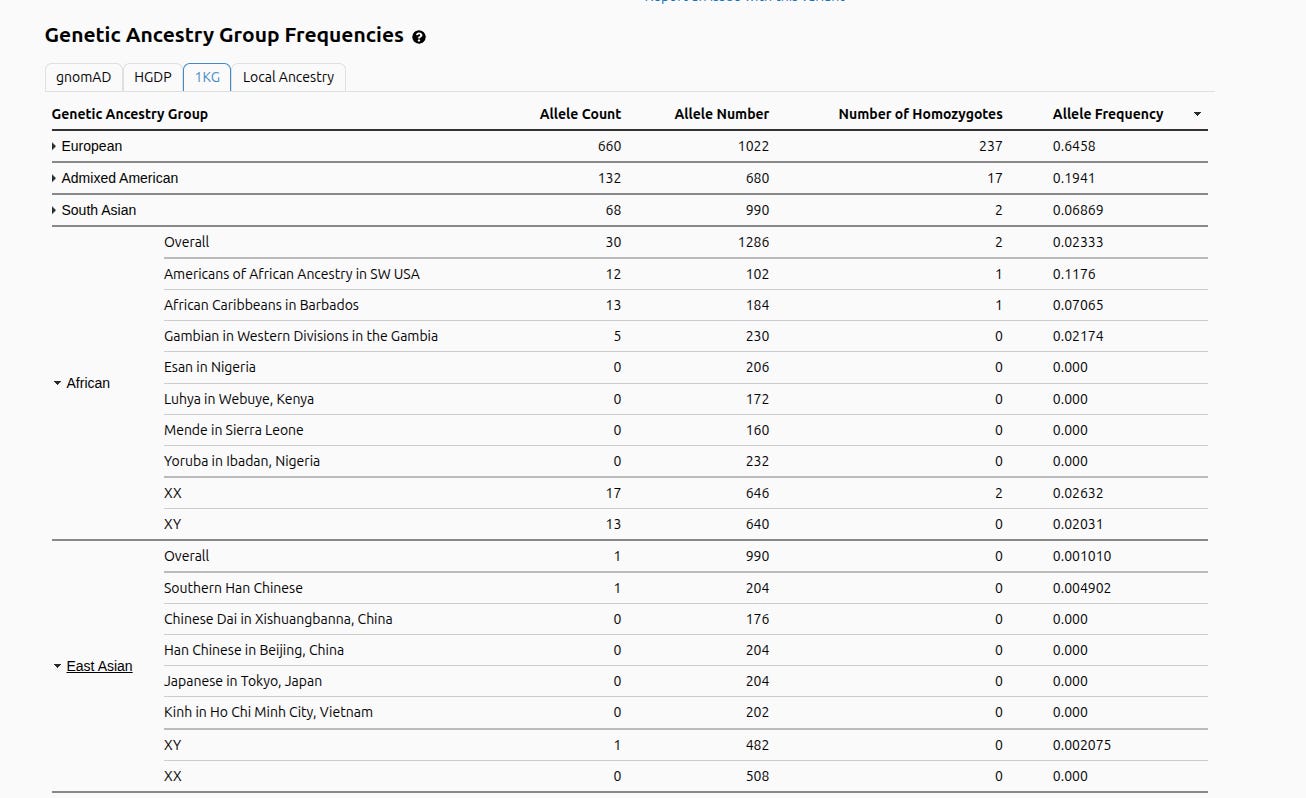

If you interpret Barbujani’s sentence at face value, it predicts that we should not be able to find loci where an allele is present at appreciable frequency in one population while another population is homogeneous for the alternative state. But the genetic variant in the HERC2/OCA2 region - rs12913832 - is precisely this: the “light-eye” allele is common in Europeans, while it is absent in several sub-Saharan African and East Asian groups. The table below shows the pattern directly in gnomAD’s population frequency breakdown.

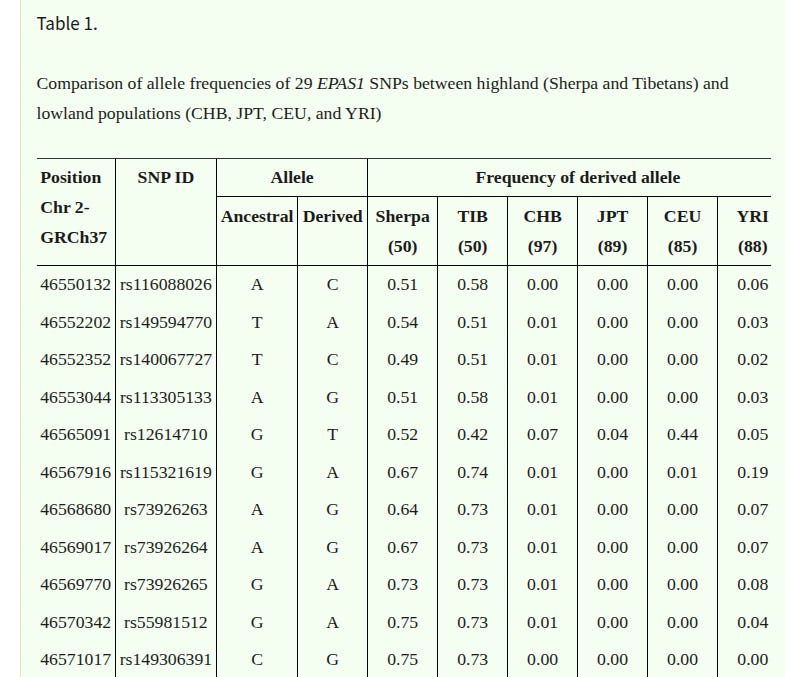

The EPAS1 haplotype enriched among Tibetans is the textbook case of high-altitude adaptation via Denisovan introgression: selection pushed it to high frequency because it improves physiological performance under chronic hypoxia, even though it remains non-universal within Tibetans; in global reference panels it is essentially absent outside East Asia, appearing at most at very low frequency in Han Chinese (Huerta-Sánchez et al., 2014).

As the authors note “In that region, the most common haplotype in Tibetans is tagged by the distinctive five-SNP motif (AGGAA; the first five SNPs in Fig. 2), not found in any of our 40 Han sample. […] Therefore, apart from one CHS and one CHB individual, none of the other extant human populations sampled to date carry this five-SNP haplotype. Notably, the Denisovan haplotype at these five sites (AGGAA) exactly matches the five-SNP Tibetan motif”.

In a subsequent study, this introgressed signal was also documented in a genetically and geographically close population, the Sherpa (Bhandari et al., 2016).

One could object that this sort of differentiation hinges on haplotypes (specific combinations of SNPs) rather than on single variants. The haplotype is the biologically relevant unit here because it is the vehicle of introgression and the object of selection, but the differentiation is not confined to this: it manifests in allele frequencies at individual SNPs that tag the introgressed tract.

Table 1 in Bhandari et al. makes this explicit. Several of the derived alleles that are common in Sherpa and Tibetans are absent or near-absent in the comparison populations they report (depending on the SNP and reference group).

Barbujani’s fatal slip on the definition of race

When Odifreddi presses Barbujani for a definition of race, Barbujani offers an operational one: if DNA allows you to assign an individual to a population or geographic origin with precision, as primatologists can allegedly do with chimpanzees, then it makes sense to talk about races. In humans, he claims, this cannot be done.

This is patently false, and Barbujani must know it.

This is the premise of modern ancestry inference. A simple principal component analysis already separates major continental origins and resolves finer structure within Europe; supervised models push the resolution even further. Consumer services like 23andMe build an entire product on the same fact: human genomes carry enough structured signal to classify people, probabilistically but with high accuracy, into ancestry clusters.

I tested this in a simple way: I projected my own genotype onto a reference PCA and it landed where it should: near the middle of the Northern Italian cluster. I did this with other samples and the results were always accurate.

Barbujani then claims that there are no characteristics shared by all members of a geographic population. As a literal statement it’s the kind of thing a non-geneticist might say, but coming from a geneticist it’s more revealing: it smuggles in a straw standard—universal, exception-free markers—and then declares victory when biology fails to meet it. Population genetics doesn’t work that way. It works by aggregating weak signals across many loci, exactly what PCA and related methods do. Structure is inferred from coordinated frequency shifts, not from one magical allele that never misclassifies anyone.

Odifreddi makes another important logical argument when the discussion turns to Neanderthals. If species are traditionally defined as reproductively isolated units, then the now well established interbreeding between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens creates a problem. Whatever names we prefer, the boundary was not absolute.

From this he derives a dilemma. Either Neanderthals and modern humans were not truly separate species, in which case they become subdivisions within a single species, something very close to what people ordinarily mean by races. Or we must admit that biologists already work with flexible, elastic concepts of species that tolerate gene flow and partial separation.

Once that admission is made, the objection that race is unusable because it lacks sharp borders loses much of its force. The absence of a clean cutoff has not prevented genetics from talking about species. Why should it suddenly prohibit talking about races?

The San Marino standard

Near the end of the debate the exchange tightens around a concrete challenge. Odifreddi asks whether a systematic difference in archaic ancestry would count: if some genomes lacked Neanderthal DNA while others carried it, would that constitute a racial difference?

In other words, he asks whether a large, systematic contrast would ever be sufficient.

Barbujani’s reply is revealing. He proposes a thought experiment: if every inhabitant of San Marino lacked Neanderthal DNA while everyone else in the world possessed it, he would happily concede a “San Marino race.” But, he immediately adds, examples of that kind do not exist.

Notice what this argument does. It quietly raises the bar from “can we detect meaningful structure?” to “does a population differ from everyone else on Earth at once?”

Once the bar is placed there, almost nothing in evolutionary biology could pass it.

If reciprocal fixation were the gold standard, a remarkable amount of accepted biological knowledge would suddenly become invalid. The European-associated lactase persistence allele is not present in every European, yet the frequency gradients are large enough to generate clear regional differences in adult lactose digestion (Itan et al., 2010). The European-specific lactase persistence allele (rs4988235 A) is present in Europe but absent in unadmixed African and East Asian populations.

Variants in HERC2/OCA2 are far from fixed even in northern Europe, but they still create conspicuous contrasts in eye-color distributions (Donnelly et al., 2012) and similarly for the already cited Sherpa high altitude adaptation example.

And the implication extends beyond humans. In zoology and botany, subspecies are frequently defined in the presence of gene flow, hybrid zones, and overlapping variation. Diagnoses are typically probabilistic; individuals are assigned with high likelihood, not perfect certainty. If we demanded that every member of group A carry one allele and every member of group B another before allowing taxonomic recognition, many named subspecies would evaporate overnight. Biologists do not adopt such a rule because they understand that evolution rarely produces immaculate boundaries.

Why, then, does the fixation argument remain attractive in the human case? Because it performs an important symbolic function. It reassures audiences that biology has not carved humanity into sealed natural castes.

It is worth seeing the exchange in their own words.

“The question remains: if there were a genome that lacks Neanderthal DNA compared to others that have it, would that constitute a racial difference or not?”)

(“Comunque rimane la domanda: se ci fosse un genoma in cui non c’è del DNA neandertaliano rispetto a coloro che invece ce l’hanno, questo sarebbe una differenza di razza oppure no?”)

In other words, he asks whether a large, systematic genetic contrast would count.

Barbujani’s answer is revealing. He replies:

“If you find that all the inhabitants of San Marino lack Neanderthal DNA and everyone else in the world has it, I will be happy to say that there is a San Marino race. Examples like this do not exist.”

(“Se tu trovi che tutti gli abitanti di San Marino non hanno il DNA neandertaliano e tutti quanti gli altri abitanti del mondo ce l’hanno, io sarò felice di dire che c’è una razza di San Marino. Esempi di questo genere non esistono.”)

The standard has quietly shifted from “is there measurable, biologically relevant differentiation?” to something closer to a stage trick: a population that differs from everyone else on Earth simultaneously. That is not how subspecies are treated in zoology, not how structure is inferred in population genetics, and not how adaptation is studied in practice.

The real question is: Do some human populations carry substantial archaic ancestry that other populations essentially do not? The answer is yes, without a doubt. West African populations have been modeled as carrying on the order of 2–19% ancestry from a deeply diverged “ghost” archaic lineage (Durvasula & Sankararaman, 2020). By contrast, Denisovan introgression is absent in African genomes (Mondal et al., 2025), while it is well documented at appreciable levels in parts of Southeast Asia and Oceania (Browning et al., 2019).

Barbujani shoots himself in the foot

Even Barbujani’s favored illustrative case - the German Shepherd - often contrasted with a Dachshund to highlight breed-level sharpness, fails to meet his San Marino threshold. He appeals to coat-color genetics, noting the predominance, close to fixation in many lines, of the sable or wild-type allele (“SS”): an unfortunate Nazi-coded joke that drew no smiles from the other two guests. The allele underlies the breed’s grizzled, wolf-like look, a trait reinforced by historical breed standards and working selection. Yet the underlying coat-color alleles aren’t unique to German Shepherds: related ASIP variants that produce sable/agouti banding occur across multiple breeds (especially spitz and herding types) and in mixed dogs. Breed standards can push an allele toward fixation within a lineage, but no single coat locus delivers the kind of globe-wide, “present only here and nowhere else” uniqueness implied by the San Marino hypothetical. If German Shepherds qualify as a coherent biological entity despite lacking such immaculate uniqueness, the demand for perfect allele-level boundaries in humans appears less a consistent scientific principle and more a rhetorical safeguard against essentialist interpretations of population structure.

Barbujani started on the wrong foot, and he ended up using German Shepherds to shoot himself in it (no Nazi joke intended).

References

Brower, A. V. Z. (2013). Introgression of wing pattern alleles and speciation via homoploid hybridization in Heliconius butterflies: A review of evidence from the genome. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1752), 20122302. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2302

Bhandari, S., Zhang, X., Cui, C., Yangla, Liu, L., Ouzhuluobu, Baimakangzhuo, Gonggalanzi, Bai, C., Bianba, Peng, Y., Zhang, H., Xiang, K., Shi, H., Liu, S., Gengdeng, Wu, T., Qi, X., & Su, B. (2016). Sherpas share genetic variations with Tibetans for high-altitude adaptation. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 5(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.264

Browning, S. R., Browning, B. L., Zhou, Y., Tucci, S., & Akey, J. M. (2018). Analysis of human sequence data reveals two pulses of archaic Denisovan admixture. Cell, 173(1), 53–61.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.031

Cahill, J. A., Stirling, I., Kistler, L., Salamzade, R., Ersmark, E., Fulton, T. L., Stiller, M., Green, R. E., & Shapiro, B. (2015). Genomic evidence of geographically widespread effect of gene flow from polar bears into brown bears. Molecular Ecology, 24(6), 1205–1217. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13038

Durvasula, A., & Sankararaman, S. (2020). Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations. Science Advances, 6, eaax5097. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax5097

Huerta-Sánchez, E., Jin, X., Asan, et al. (2014). Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature, 512, 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13408

Itan, Y., Jones, B. L., Ingram, C. J., Swallow, D. M., & Thomas, M. G. (2010). A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC evolutionary biology, 10, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-10-36

Lan, T., Leppälä, K., Tomlin, C., Talbot, S. L., Sage, G. K., Farley, S. D., Shideler, R. T., Bachmann, L., Wiig, Ø., Albert, V. A., Salojärvi, J., Mailund, T., Drautz-Moses, D. I., Schuster, S. C., Herrera-Estrella, L., & Lindqvist, C. (2022). Insights into bear evolution from a Pleistocene polar bear genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(24), e2200016119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200016119

Mondal, M., André, M., Pathak, A. K., et al. (2025). Resolving out of Africa event for Papua New Guinean population using neural network. Nature Communications, 16, 6345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61661-w

Yengo, L., Vedantam, S., Marouli, E. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05275-y

"Barbujani, by contrast, defended what has become the mainstream (politically correct) formulation in modern human genetics: variation exists, sometimes visibly and medically relevant, but it does not divide humanity into discrete biological races."

Barbujani is a woke leftist ideologue.

"Barbujani starts on the wrong foot by opening with a familiar metaphor: the genome as a 6.5-billion-letter text whose “grammar” we partly understand but whose “syntax” still escapes us. From that he draws a reassuring conclusion: even if we read your entire genome, we still cannot predict whether you will get cancer or diabetes, or even how tall you will be."

For me, one of the most important areas of research for the ascent of humanity is the use of psychometrics and genetics to determine genetic influences on positive traits and to enhance humanity.